A Chronicle of Repatriation Relief Efforts

A Chronicle of Repatriation Relief Efforts

P.54–62

- Author

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

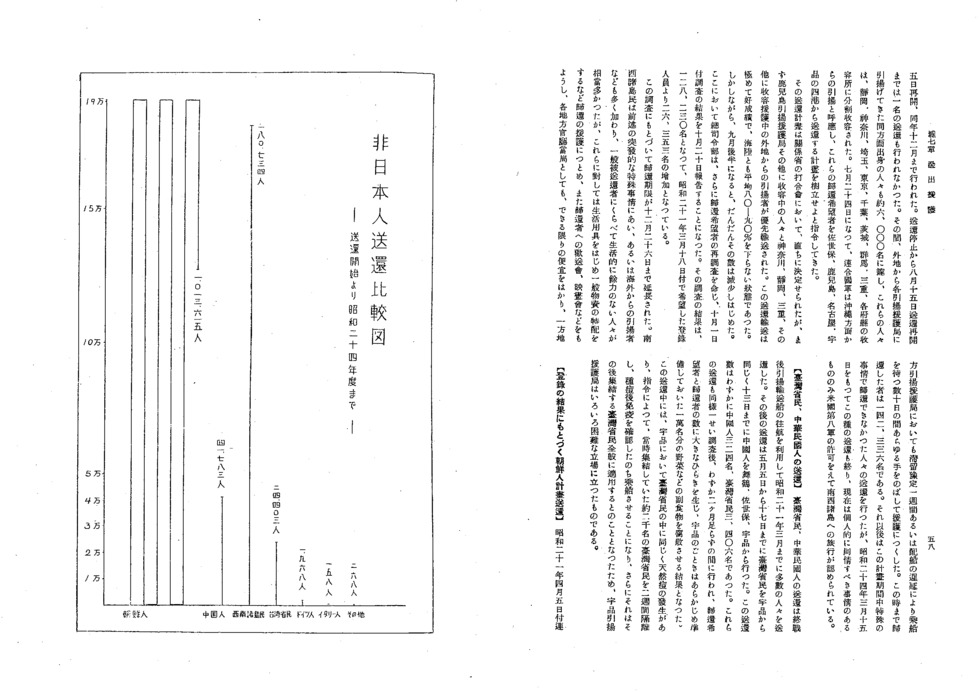

Chapter 7 Transport Support

- Setting the Plan for Repatriation

On August 21, 1945, a policy to release conscripted laborers, including the Koreans who were forced to migrate to Japan, was first approved at a meeting of vice ministers. With the sudden change in circumstances at the end of the war and the future uncertainty they faced, it was natural that those who were freed would be overjoyed, and at the same time, would be in a rush to return home. However, it went beyond simply rushing to return home—as positions were reversed, there was an ominous mood permeated the entire country, and particularly in Kitakyushu and Hokkaido, violent incidents were occurring. Making arrangements to allow those people to return home right away was one of the pressing issues the government faced at the end of the war, along with repatriating Japanese nationals overseas as quickly as possible. On September 1, 1945, under Bureau of Police and Public Security Notice No. 3, “Regarding Emergency Measures for Korean Mass Migrant Workers, etc.,” the Ministry of Welfare and the Ministry of Home Affairs jointly notified all prefectural governors that transport would begin soon and directed them to determine the order of priority for transport and to instruct employers that they must designate someone to accompany the returnees all the way to Busan.

At that time, there had been no survey done yet to get a definitive number of people to be transported. By September 25, the Welfare Ministry’s Social Bureau estimated that the number of “people of Korean origin desiring repatriation to their country” was 910,636. This number was derived by taking the total number of Koreans living in Japan as of the end of 1944—1,911,307—and subtracting the number of mass migrant workers in Japan at that time—243,513—to find the general population of Koreans in Japan (1,667,794). They then estimated that 40 percent of that general population would want to return home (667,123) and added back in the number of mass migrant workers to produce the basic number for transport. However, the basis for this calculation did not include the mass migrant workers who had been brought to Japan in 1945. (The approved number to be admitted in FY1945 was 50,000.) Not only that, but even assuming that the basic numbers were an approximation, there were various conditions that affected whether or not someone wanted to return to their country of origin. As an individual question, it was also exceedingly difficult to ascertain. Indeed, the actual number of people returning home greatly differed from the projected numbers, which had a major impact on the transport work. Meanwhile, as repatriation to Korea began in mid-September, Koreans rushing to go home began arriving one after another in Shimonoseki and Kitakyushu, exceeding the capacity to transport them, which led to even further chaos. On September 28, the Japanese government issued a notice regarding “Emergency Measures to Deal with Korean and Taiwanese Nationals Living in Japan relating to the End of the War” (Ministry of Welfare Health-No. 152), which clarified the intent of the government in detail regarding the spirit and specific plans of the emergency measures for the return of former fellow citizens to their countries. In particular, it restated the policies, for example assigning the Offices for Civilian Repatriation to provide support to the ports of embarkation and assigning the Koseikai and Taiwan Kyokai (Taiwan Association), which had been providing guidance for the Korean and Taiwanese in Japan up until that time, to provide guidance, rest, and so on during the voyage. In response to this, the overall intent of the Occupation Forces with regard to the repatriation of “non-Japanese” was decided on November 1, 1945. From October 25 on, in order to get control of the transportation, the “planned transport certificates” that had been issued up until then by the local Koseikai and business operators were now to be issued by each prefectural governor starting on November 13 at 00:00, and a large-scale transport plan was created that took each Local Railway Bureau as a block and assigned the number of passengers to be transported, thereby strengthening the system of planned transport certification for returning Koreans. The Chuo Koseikai that had been acting on behalf of Koreans since the end of the war was dissolved as of October 15. Through these measures, by December 1945, the transport of veterans, conscripts, mass migrant workers, and other priority groups was nearly completed.

At the time, the designated ports of embarkation were Senzaki (for Koreans), Hakata (Koreans and Chinese from North China), Kagoshima (Chinese from Central China), and Kure (Koreans, Chinese from North and Central China), but in fact there were orders given to use Sasebo, Otaru, Muroran, Hakodate, and other locations as well. In addition to the designated ports above, in January 1946, after general transport began, the work of transport support was assigned to Repatriation Relief Bureaus in Sasebo, Otake, Ujina, Nagoya, and Uraga, and to the Yokohama Relief Office.

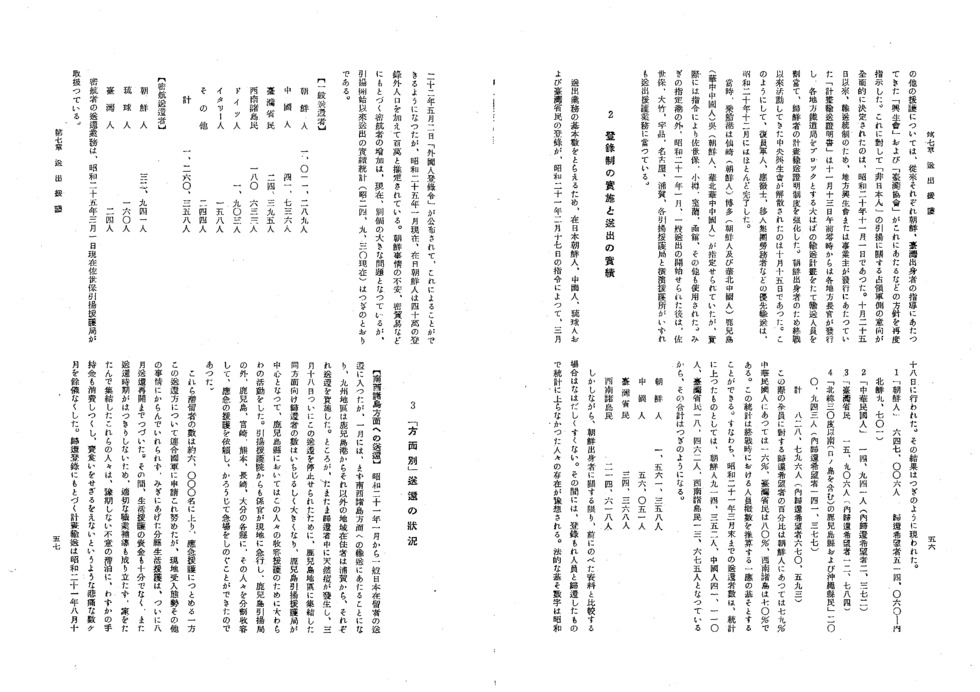

- Implementation of the Registration System and Actual Transport Results

In order to ascertain the basic number of people to be transported, on February 17, 1946, it was ordered that Koreans, Chinese, Ryukyuans, and Taiwanese living in Japan be registered, which was done on March 18. The result was as follows:

- Koreans 647,006 Seeking repatriation: 514,060 (Including 9,701 North Koreans)

- Chinese 14,941 (Seeking repatriation: 2,372)

- Taiwanese 15,906 (Seeking repatriation: 12,784)

- Locations south of the 30th parallel north—Kagoshima Prefecture and Okinawa Prefecture (including Kuchinoshima island) 200,943 (Seeking repatriation: 141,377)

Total: 828,796 (Seeking repatriation: 670,593)

At that time, the percentages of those indicating that they wanted to return to their home country were 79 percent for Koreans, 16 percent for Chinese, 80 percent for Taiwanese, and 70 percent for the Southwest Islanders. These statistics can roughly serve as the basis for calculating the approximate number of these people living in Japan at the end of the war. In other words, in addition to those people, the number who had already been repatriated as of the end of March 1946 according to the statistics was 914,352 Koreans, 41,110 Chinese, 18,462 Taiwanese, and 13,675 Southwest Islanders, resulting in the following totals:

Korean 1,561,358

Chinese 56,051

Taiwanese 34,368

Ryukyu Islander 214,618

However, looking just at the number from Korea, when one compares this to the documents noted previously, the number is exceedingly low. It is probable that this gap is due to the existence of people who were missed in the registration process and those who had already returned but were not included in the statistics. The legal numerical basis was made possible by the proclamation of the “Alien Registration Ordinance” on May 2, 1949, but as of January 1950, it is estimated that there are 1,000,000 Koreans living in Japan after adding the 400,000 who are not registered as aliens. The increased number of stowaways due to the unstable conditions in Korea, smuggling, and so on, has now become a separate major issue, but the total number of people transported out of Japan since the start of repatriation is as follows (as of September 30, 1949):

【General Repatriation】

Korean 1,011,289

Chinese 41,736

Taiwanese 24,395

Southwest Islander 180,633

German 1,903

Italian 158

Other 244

TOTAL 1,260,358

【Repatriation of Stowaways】

Korean 32,941

Ryukyuan 160

Taiwanese 24

As of March 1, 1950, the repatriation of stowaways is being handled by the Sasebo Repatriation Relief Bureau.

- Status of Repatriation “by Destination”

Repatriation to the Nansei Islands:

From January 1946, the repatriation of the general civilian population residing in Japan began, and first up in January was the transport of people to the Nansei Islands. Those in the Kyushu region were repatriated from the port of Kagoshima, while those in other regions departed from Uraga. However, there was an outbreak of smallpox among those returnees, and eventually, on March 18, the repatriation efforts were suspended, resulting in a tremendous amassing of people in the Kagoshima area who were seeking repatriation to those destinations. The Kagoshima Repatriation Relief Bureau played a leading role in carrying out tremendous efforts to provide accommodation relief for these people in Kagoshima Prefecture. Officials from the Repatriation Relief Board rushed to the scene, and in addition to the Kagoshima Repatriation Relief Bureau, they requested emergency assistance from the prefectures of Kagoshima, Miyazaki, Kumamoto, Nagasaki, and Oita, seeking to divide up and accommodate these people, which just barely managed to serve as a stopgap measure.

The number of people staying there rose to about 6,000, and while the Relief Bureau worked to provide emergency relief, they also put in a request for assistance from the Allied Forces with the repatriation transport, but the Allied Forces refused to provide assistance due to the local situation or for other reasons, so the aforementioned provision of assistance by dividing people up among the prefectures lasted until the repatriation resumed in August. During that time, there were insufficient funds for living assistance, and because the timing of repatriation was not certain, there could be no appropriate vocational guidance, so these people who had packed up their homes and gathered here found themselves unexpectedly wandering about all of a sudden, forced to spend several heartbreaking months during which they had to use up what little money they had left just to get food to eat. The planned transport based on the transportation registry restarted on August 15, 1946, and continued through December of that year. From the time the repatriation was suspended through its resumption on August 15, not a single person was repatriated. During that time, the number of people from this area who had returned from overseas and gone to the repatriation relief bureaus reached about 6,000 people, and they were divided up and received at camps in the prefectures of Shizuoka. Kanagawa, Saitama, Tokyo, Chiba, Ibaraki, Gunma, and Mie. On July 24, along with the return of people from the Okinawa area, an order was issued to form plans to repatriate people who wished to return home using four ports, Sasebo, Kagoshima, Nagoya, and Ujina.

Those repatriation plans were immediately agreed upon at a meeting among the relevant ministries, and priority was placed first on transporting the people being accommodated at the Kagoshima Repatriation Relief Bureau and elsewhere and those who had returned from overseas and were being housed in Kanagawa, Shizuoka, Mie, and other locations. This repatriation transport, both by land and by sea, was very successful, handling no less than 80–90 percent on average. However, by late September, the numbers began to decrease. As a result, General Headquarters (GHQ) ordered a new survey of those wishing to return home, and the results of an October 1 survey were reported on October 20. The survey found 128,230 people wanted repatriation, which was a 26,353-person increase from those registered on March 18, 1946.

Based on that survey, the repatriation period was extended through December 26. The people from the Nansei Islands, many of whom were suddenly put in the unexpected situation described above or had been repatriated from overseas, had very little financial room to spare compared to the average person being repatriated, and so the local government authorities provided as much assistance as they could, working to provide relief such as the special provision of tools for daily living and other general supplies, as well as holding farewell parties, showing movies, and so on. Meanwhile, the local repatriation relief bureaus also extended a hand to provide all sorts of assistance during the expected one-week stay, or during the several weeks people had to wait if their ship was delayed. By the end of that period, 142,336 people had been repatriated. After that time, repatriations were carried out for people who were unable to return home during the allotted period due to special circumstances, but those types of repatriations also came to an end as of March 15, 1949, and currently, only in individual cases that are deserving of special sympathy can travel to the Nansei Islands be approved with the permission of the 8th United States Army.

Repatriation of Taiwanese and Chinese:

A large number of Taiwanese and Chinese nationals were repatriated through March 1946 using the outward voyages of ships that were bringing back Japanese nationals from overseas after the war. Subsequently, Taiwanese were repatriated from Ujina from May 5 to May 17, and Chinese from Maizuru, Sasebo, and Ujina until the 13th of that month. The number of these repatriations was a mere 324 Chinese and 3,406 Taiwanese. These repatriations similarly were carried out in a period of less than two months following the survey, and a significant gap appeared between those wanting to return to their home countries and those who were repatriated, so in places like Ujina, which had prepared vegetables and other food for side dishes in advance for 10,000 people, the result was that a lot of excess food went to waste. During this repatriation, there was also an outbreak of smallpox among the Taiwanese in Ujina, and under orders, the roughly 2,000 Taiwanese people who were assembled there at the time were quarantined for two weeks; they were allowed to board the boat after they had been vaccinated and their immunity had been checked. That rule also applied to all Taiwanese who subsequently gathered there, and so the Ujina Repatriation Relief Bureau was put in a difficult position in a number of ways.

Planned Repatriation of Koreans Based on Registration Results:

An order from the GHQ of the Allied Forces dated April 5, 1946, directed that planned repatriation must begin based on the results of the March 18 registration (with the exception of the Nansei Islands). It was ordered that from April 15 to September 30, a total of 1,000 Korean people were to be repatriated each day from Senzaki and 3,000 a day from Hakata. But the number of those who assembled according to each scheduled embarkation averaged a mere 200–250 people per day in Hakata and about 30–50 people per day in Senzaki, so the shipping plans were revised, accommodating luggage and facilitating or supplying necessities for each repatriate while at the same time seeking cooperation from all directions and focusing efforts to a great extent on increasing the enthusiasm for going home, but their efforts failed to produce results. However, from July to August, there was an outbreak of cholera in Busan, followed by rail disruptions in South Korea due to flooding, causing repeated suspensions of repatriation voyages to Korea, and as a result, the number of Koreans stuck in Hakata grew to more than 6,000 people, and combined with the roughly 6,000 repatriates who were returning to Japan each day from overseas, the Hakata Repatriation Relief Bureau was assisting more than 12,000 repatriates daily for a number of weeks in a row.

After the resumption of repatriations in August, the numbers of repatriates started to pick up slightly, but compared to the anticipated transport of 4,000 people a day, it did not exceed the 1,000–1,500 level on average.

This repatriation was also temporarily suspended as a result of issues including a general strike by rail workers in Korea, causing the already tepid response to repatriation to decrease even further. The Allied Forces happened to approve an increase in the amount of luggage repatriates could bring, raising the 250 pounds per person weight allowance for household belongings and appliances to 500 pounds and permitting 4,000 pounds or more per person of light machinery, trade tools, etc., with the permission of the military government, but despite the various efforts that the relevant actors made, they were all unexpectedly ineffective, and as a result, the period for repatriation was extended through December 15, 1946.

Repatriation of South Seas natives and Ogasawara Islanders:

In October 1946, the repatriation of natives of the South Seas region was permitted, and 24 people were returned to the former South Sea islands from the Uraga Repatriation Relief Bureau. The return of people to the Ogasawara Islands had not been approved since the end of the war, and that October, permission was granted for only persons of British or American descent to return, with 120 people departing from the Uraga bureau.

Repatriation of Manchurians and Indonesians:

After the March 18, 1946, registration, repatriation to Manchuria was not carried out, but in October, 28 people desiring repatriation embarked from Hakata. The repatriation of Indonesians was the subject of extended negotiations between the Dutch government and the United States government, but based on the survey of those desiring repatriation, 76 people were sent home from the port of Kobe, and a second group of 60 people left from the same port in late March 1947 as well.

Repatriation of Germans and Others:

The order issued on January 13, 1947, indicating that Germans must be repatriated on a boat leaving Uraga on January 28 was a different operation in nature than the previously noted examples of general repatriation.

The first difference were the repatriates to which this applied. The Germans in question were former members of the Nazi Party or similar individuals, and thus a compulsory repatriation was ordered.

Second, a “Civil Property Custodian” was assigned to oversee all of the property management and repatriation work for Germans, and the custodian and his “observer unit” went directly to the places where the Germans were residing, controlling and supervising the tasks without the involvement of the local military government; the Japanese government had to carry out all tasks (municipal and prefectural administrative divisions) under the supervision as well as the administrative guidance of the custodian.

Third, the property that the repatriates were allowed to bring with them was limited, and in terms of the property left behind, one property recipient was selected for each family or individual and the recipients had to submit to various orders before the repatriation work was totally finished.

Fourth, prior to their return, they were subject to required medical and hygienic measures including being quarantined.

Fifth, the expense of the materials, labor, and other aspects of the Germans’ repatriation was to be covered by the Japanese government.

Sixth, at the Uraga Repatriation Relief Bureau, relief facilities were provided, particularly special accommodations that took a month to prepare, an allowance, and so on. The total amount spent on these 1,069 German repatriates was approximately 6,000,000 yen. As a result, the Germans and Austrians left touching words to the officers in charge who had been earnest from start to end for a hearty send-off, and on February 15, they departed on the Marine Jumper for their beloved homeland in Europe.

Each of the agency officials involved spent about two months on site prior to and after the departure, setting up the special office, and tasked with carrying out difficult repatriation relief duties day and night—even in the snow. The second repatriation of Germans took place in August of 1947 with 807 people and the third in March 1948 with 27 people from the Yokohama Relief Office. The third group returned by plane from Haneda.

Repatriation to North Korea:

After the end of the war, North Korea—above the 38th parallel north—was placed under the control of the Soviet Union, and since no international agreement had been reached on the repatriation of Japanese from this area, the repatriation of Koreans to the area was also delayed, but in January 1947, instructions were communicated that repatriation would start in early March, and so a survey of those seeking repatriation was carried out at the end of January, but compared to the 9,071 people who had registered as desiring repatriation on March 18, 1946, the number this time was a mere 1,413 people, and when the Taian Maru set sail from Sasebo on March 15, 1927, that number had further dropped to just 224.

Repatriation of Italians:

According to an Allied Forces order dated February 19, 1947, there were 130 Italians repatriated from Uraga, and after these repatriations of the Germans and Italians, the Uraga Repatriation Relief Bureau was closed.

- Another Side of Transport Support

The combination of a number of conditions, such as Japan’s position after having lost the war and various transportation issues, meant that transport support efforts faced more difficulties than can adequately be described. The truth about the substantial efforts made by the local repatriation relief bureau personnel lies hidden in the accounts of the hardships faced by those who offered assistance by accompanying repatriates from Hokkaido to Busan or to Senzaki, or in the incidents reported at the repatriation bureaus. In particular, they experienced exceptional pain when it came to sending away stowaways. One employee at the Sasebo Repatriation Relief Bureau writes about the transport support efforts as follows:

“When we were assigned to work on transporting people to Korea and the Nansei Islands, we were confronted with a lot of unexpected things. In any case, we had to treat them as ‘non-Japanese.’ We were very careful about these repatriates, but there were hot-blooded young workers and it took a lot of effort for them to keep their emotions in check, and there were times when they would request backup from older colleagues. When I think about it now, there were many amusing incidents.”

Stand-Ins:

When there were many people returning to Korea, a truck was sent from the bureau to Haenosaki Station where they were picked up as a group. Then, at the gate, we compared the repatriation certificate and the actual person, and if there was nothing incorrect or suspicious, they would be ushered on to the person in charge of transport, but from time to time there would be a stand-in mixed in, and it was something you could not laugh at or get angry about. A “stand-in”. . . that refers to the case that someone plots to buy a repatriation certificate from a person who has given up on their wish to go back to their country and then tries to enter the bureau that way. When we did the verification process at the gate, if we called for ‘Mr. Lee,’ for example, and there was no response, we skipped over that person and continued the process, and then at the end, someone would complain, ‘You didn’t call my name.’ When we looked into it, we would discover that this was a so-called stand-in whose real name was ‘Mr. Kim.’ In other words, the person was inadvertently waiting to hear his real name and so his cover story was blown.

Or there were people whose age written on their certificate was clearly more than ten years different from their actual age. At first, they insisted that the Japanese government office must have made a mistake, but gradually their true identity would come out, and in the end they would admit that they were a stand-in and turn back. Later, they had to bring a residence certificate with a photo on it, so that eliminated improper admittances for the most part, but conversely, there were stories of the gate workers suffering because of the mistakes of the Japanese government agencies…

The absolute requirement for a repatriation certificate was to get certification from the prefectural governor, which was obtained through the mayor of the municipality in which the person resided, but people would sometimes come, perhaps by mistake, without having the certification of the governor or without their mayor’s endorsement. When we looked into it, we would find that it was a complete oversight on the part of the Japanese agencies. When that happened, we would be the ones who suffered inconveniences—we had to explain the mistake in the documents and tell them that they regrettably would have to go back and get the additional information, but the person would just keep repeating over and over that it was the Japanese government agency’s mistake…

“I had completely cleared out of my home, and I do not have money to go back. The repatriation relief bureau is a branch of the government, so you have to temporarily pay all of my travel allowance—I think that is your duty. But sir, up until just the other day, we were all living together as Japanese people, so please overlook…” It was extremely hard to listen as they would beg for assistance, trying both ranting and sweet-talking us.

Going Out:

Under the orders of the Occupation Forces, repatriates were not allowed to leave the bureau as a rule, but for truly unavoidable reasons such as luggage checks, going to the hospital, and so on, we would get the confidential approval of the Occupation Forces and permission was granted for a group to leave the premises once a day under the responsibility of the head of the bureau (and led by an assigned employee). When leaving the bureau, people would line up in the standard way and would go out through the inspection station without any trouble, but when they returned to the bureau, it seemed like every day there would be a ruckus, and it caused tremendous grief for the employees.

More precisely, depending on what the person’s business was, it would take different amounts of time, and since the understanding was that if people did not finish by the appointed time to gather for their return and if all members were not gathered as a group at the gate, then they could not be inspected and processed for reentry, those who got back early would wait in the vicinity of the gate, but waiting for two or three hours at the height of summer, for example, was unbearable. As a result, quarrels would break out as people would get into arguments, scuffles, or even fistfights with those who came late, and bureau employees unfortunate enough to play the role of peacemaker sometimes fell victim to a stray blow, so if you did your work by the rules, people would hold a grudge against you or bawl at you, but if you eased up a bit, they were apt to behave irrationally, so the workers experienced an unseen struggle.

Deep Emotions:

If I remember correctly, it was mid-July 1947, just before Obon. The leader of a group of Koreans in the No. 9 quarters who were awaiting their return home came to see me. “At last we’ll be shipping out the day after tomorrow. I apologize for the inconvenience we’ve caused all of you for such a long time. Actually, all of our group talked about wanting to do something to thank you, and since tomorrow is Obon, and even in our homeland of Korea we traditionally make a grand event that day with a festival, meal, and so on, we were thinking of inviting everyone from the main gate, but since everyone is busy with the upcoming departure and we couldn’t get all the materials we needed, we unfortunately had to give up on that plan. I’m very sorry, but I’ve brought some fruit and cigarettes, so I hope you’ll accept these.”

I was so touched that I could not say a word, and instinctively I shook his outstretched hand firmly. As we parted ways, I wished him a safe voyage, and even today, I remember that moment fondly.

P.85

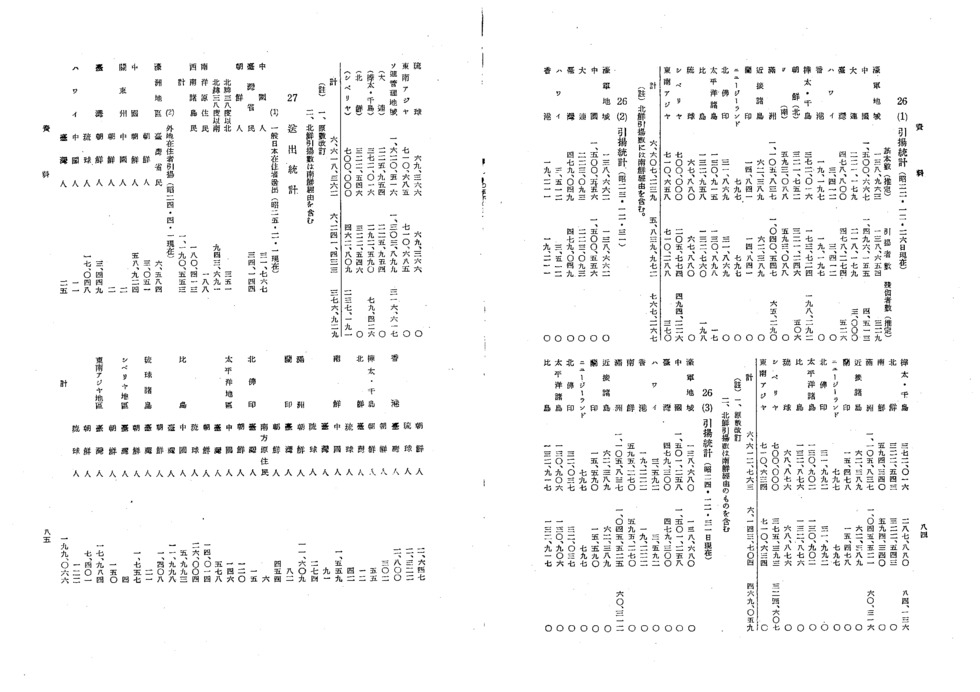

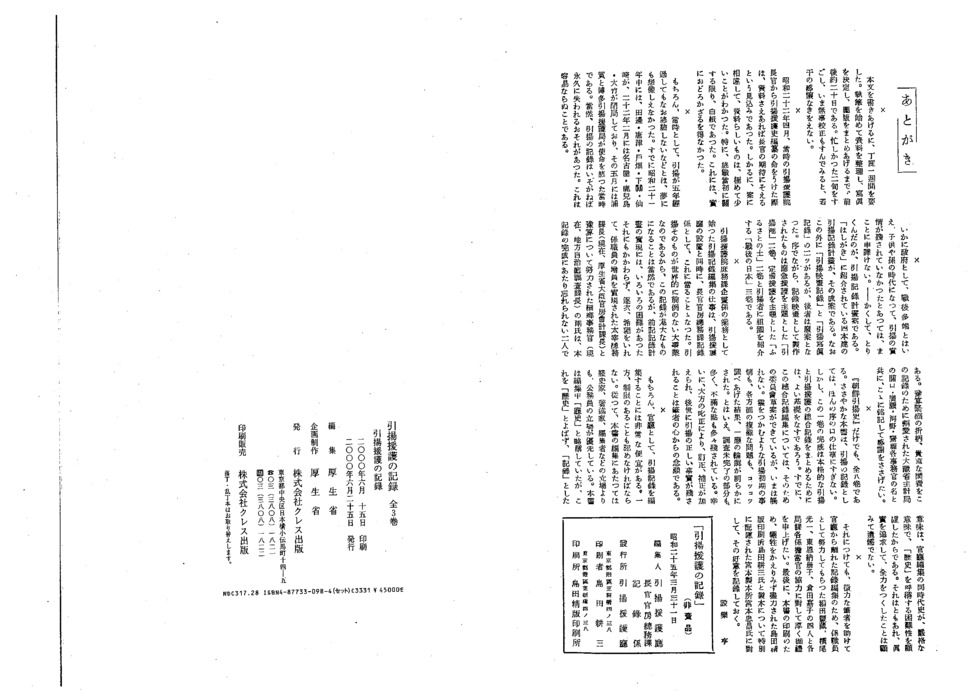

27 Total persons transported

(1) General persons residing in Japan transported out of Japan (as of February 1, 1950)

Chinese 31,767

Taiwanese 34,144

Korean

North of 38th parallel north 351

South of 38th parallel north 943,691

South Seas natives 188

Southwest Islanders 180,413

Total 1,190,553

(2) Repatriation of individuals residing overseas (as of April 1, 1949)

Australian region Taiwanese 6,584

Korean 3,051

China Korean 58,924

Kwantung Chinese 2

Korean 2

Taiwan Korean 3,449

Ryukyuan 17,048

Hawaii Chinese 11

Taiwanese 25

Korean 2,647

Ryukyuan 2,322

Hong Kong Taiwanese 2,800

Korean 302

Karafuto/Chishima Korean 55

North Korea Taiwanese 12

Ryukyuan 42

South Korea Chinese 1,559

Taiwanese 91

Ryukyuan 274

Manchuria Korean 11,609

Dutch East Indies Taiwanese 82

Korean 454

South Seas natives 6

- French Indochina Taiwanese 15

Korean 120

Pacific region Chinese 146

Taiwanese 578

Korean 14,014

Ryukyuan 26,004

Philippines Chinese 5,993

Taiwanese 11,998

Korean 1,408

Ryukyu Islands Taiwanese 21

Korean 1,757

Siberia region Taiwanese 4

Korean 150

Southeast Asia region Taiwanese 17,984

Korean 7,401

Ryukyuan 122

Total 199,066