Mechanisms for Determining Colliery Wages: An Introduction

Statistics Study Group

Takafusa Nakamura

Research Document No.8

Japan Labor Association Survey and Research Division

- Author

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Table of Contents

- Foreword. 3

- Colliery Wages and Farm Wages: First Period. 3

- Mine Worker Wages and Labor Supply and Demand . 6

- Establishment of Labor Management 10

- Postwar Control Mechanisms. 12

- Wage Determination after the Abolition of Controls. 13

1. Foreword

In this paper, I would like to examine the assumptions underlying mechanisms for determining colliery wages in the present day through a historical review of such determination mechanisms in the past. While doing so will necessarily entail considering quite a broad range of conditions, I would like to limit our present exercise to one that handles the issue schematically.

If we categorize wages for mine workers with consideration to worker origins and aspects of labor management, we may consider them in terms of following historical periods:

- First Period: prior to the 1918 rice riots,

- Second Period: from 1918 until the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War

- Third Period: from the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War until the Dodge Line Period around 1949

- Fourth Period: from 1949 up to the present day

Below, I will attempt to provide a broad sketch of each of these periods.

2. Colliery Wages and Farm Wages: First Period

In the First Period, mine workers were primarily “pit workers” (jikōfu) from nearby farming villages, and their turnover rate was also high. In particular, the prevalence of the mining camp (hanba) system meant that instances of direct labor management by the companies were rare. Wages during this period were extremely low, and largely prescribed by the living standards in nearby farming villages, so that until the end of the Meiji period wages remained more or less on a par with those of agricultural day-laborers and then seemed to turn upward.

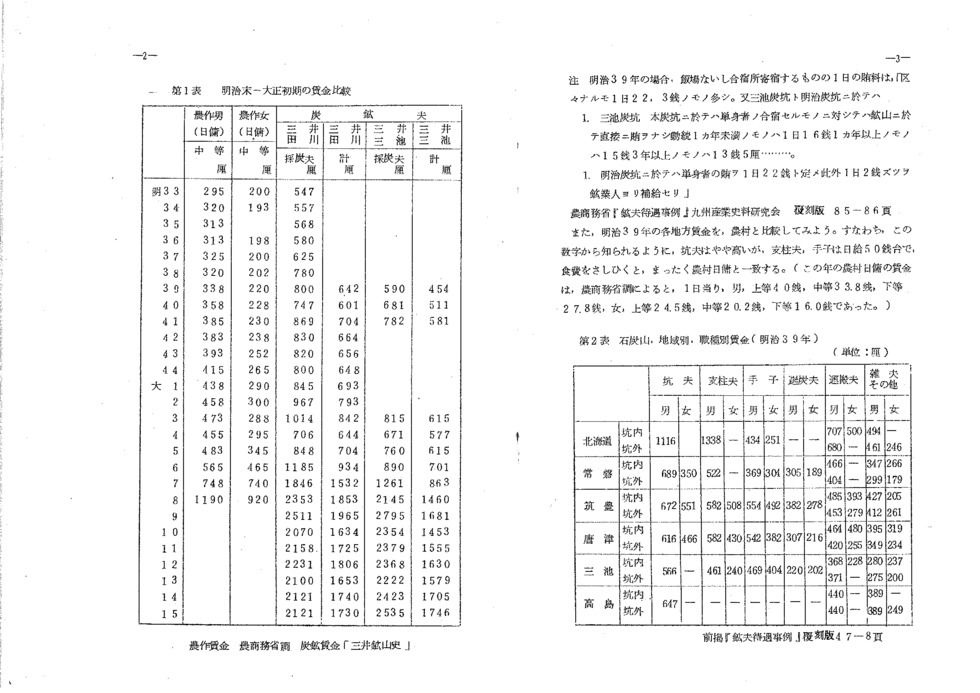

This fact is generally evident from Table 1, which compares longitudinal data for mine worker wages obtained from the Mitsui mines at Tagawa and Miike with agricultural day-laborer wages. Looking at these figures alone, there would seem to be a considerable difference, but since 22–23 sen for meals and 2–3 sen for renting a futon mattress would be deducted from mine workers’ wages and since farm workers would receive meals on top of their wages, it seems there is no substantial difference.

Table 1: Comparison of Wages for the Late Meiji / Early Taishō Periods

(Units: rin = 1/1000 JPY)

|

Year |

Farmworker (day-laborer) |

Coal miner |

||||

|

Man |

Woman |

Mitsui Tagawa |

Mitsui Miike |

|||

|

Second-class |

Second-class |

Face worker |

Total |

Face worker |

Total |

|

|

1900 |

295 |

200 |

547 |

|

|

|

|

1901 |

320 |

193 |

557 |

|

|

|

|

1902 |

313 |

|

568 |

|

|

|

|

1903 |

313 |

198 |

580 |

|

|

|

|

1904 |

325 |

200 |

625 |

|

|

|

|

1905 |

320 |

202 |

780 |

|

|

|

|

1906 |

338 |

220 |

800 |

642 |

590 |

454 |

|

1907 |

358 |

228 |

747 |

601 |

681 |

511 |

|

1908 |

385 |

230 |

869 |

704 |

782 |

581 |

|

1909 |

383 |

238 |

830 |

664 |

|

|

|

1910 |

393 |

252 |

820 |

656 |

|

|

|

1911 |

415 |

265 |

800 |

648 |

|

|

|

1912 |

438 |

290 |

845 |

693 |

|

|

|

1913 |

458 |

300 |

967 |

793 |

|

|

|

1914 |

473 |

288 |

1,014 |

842 |

815 |

615 |

|

1915 |

455 |

295 |

706 |

644 |

671 |

577 |

|

1916 |

483 |

345 |

848 |

704 |

760 |

615 |

|

1917 |

565 |

465 |

1,185 |

934 |

890 |

701 |

|

1918 |

748 |

740 |

1,846 |

1,532 |

1,261 |

863 |

|

1919 |

1,190 |

920 |

2,353 |

1,853 |

2,145 |

1,460 |

|

1920 |

|

|

2,511 |

1,965 |

2,795 |

1,681 |

|

1921 |

|

|

2,070 |

1,634 |

2,354 |

1,453 |

|

1922 |

|

|

2,158 |

1,725 |

2,379 |

1,555 |

|

1923 |

|

|

2,231 |

1,806 |

2,368 |

1,630 |

|

1924 |

|

|

2,100 |

1,653 |

2,222 |

1,579 |

|

1925 |

|

|

2,121 |

1,740 |

2,423 |

1,705 |

|

1926 |

|

|

2,121 |

1,730 |

2,535 |

1,746 |

Farm wages from Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce surveys; colliery wages from Mitsui kōzan-shi

[A History of the Mitsui Mines][1]

I would also like to compare wages from various regions in 1906 with farm wages. That is, as we can know from these figures, while pit workers had slightly higher wages, timberers and helpers received on the order of 50 sen, which, when we subtract the cost of meals, is exactly consistent with agricultural day-laborers. (Daily wages for agricultural day-laborers in this year, according to figures from the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, were as follows. Among men, first-class workers received 40 sen per day, second-class 33.8 sen, and third-class 27.8 sen. Among women, first-class workers received 24.5 sen per day, second-class 20.2 sen, and third-class 16.0 sen.)

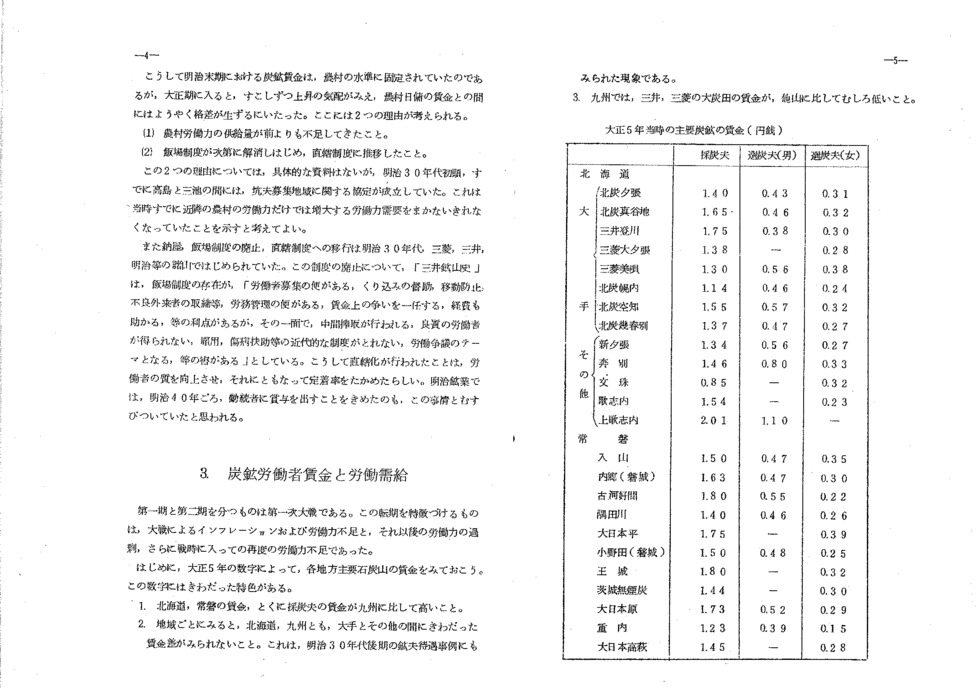

Table 2: Colliery Wages by Region and Occupation (1906)

(Units: rin)

|

|

Pit worker (kōfu) |

Timberer (shichūfu) |

Helper (teko) |

Dresser (sentanfu) |

Porter (unpanfu / atomuki) |

Menial workers / Miscellaneous |

|||||||

|

M |

W |

M |

W |

M |

W |

M |

W |

M |

W |

M |

W |

||

|

Hokkaidō |

Pit |

1,116 |

— |

1,338 |

— |

434 |

251 |

— |

— |

707 |

500 |

494 |

— |

|

Surface |

680 |

— |

461 |

246 |

|||||||||

|

Jōban |

Pit |

689 |

350 |

522 |

— |

369 |

304 |

305 |

189 |

466 |

— |

347 |

266 |

|

Surface |

404 |

— |

299 |

179 |

|||||||||

|

Chikuhō |

Pit |

672 |

551 |

582 |

508 |

554 |

492 |

382 |

278 |

485 |

393 |

427 |

205 |

|

Surface |

453 |

279 |

412 |

261 |

|||||||||

|

Karatsu |

Pit |

616 |

466 |

582 |

430 |

542 |

382 |

307 |

216 |

464 |

480 |

395 |

319 |

|

Surface |

420 |

255 |

349 |

234 |

|||||||||

|

Miike |

Pit |

566 |

— |

461 |

240 |

469 |

404 |

220 |

202 |

368 |

228 |

280 |

237 |

|

Surface |

371 |

275 |

200 |

||||||||||

|

Takashima |

Pit |

647 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

440 |

— |

389 |

— |

|

Surface |

440 |

— |

389 |

249 |

|||||||||

Source: Kōfu taigū jirei, pp. 47–48, op. cit.

Thus, colliery wages at the end of the Meiji period were fixed at the levels then prevailing in the farming villages. Coming into the Taishō period, however, we find signs of a gradual increase, eventually giving rise to a gap between mine wages and those of agricultural day-laborers. There are two conceivable reasons for this

- A decrease in the rural labor supply compared to previously

- A shift to direct control with the gradual disappearance of the hanba

While there are no concrete materials directly supporting either of these two reasons, by the beginning of the 1890s, an agreement concerning regions for recruitment of pit workers had already been reached between Takashima and Miike. This may be considered to suggest that the labor force in nearby villages was no longer in itself sufficient to meet the growing demand for workers.

In addition, the abolition of the hanba system and the transition to direct control was already underway at several mines in the 1890s, including at the Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Meiji mines. Regarding the abolition of this system, Mitsui kōzan-shi [A History of the Mitsui Mines] describes how the existence of the hanba system “had several advantages, such as that it was convenient for recruiting laborers as well as for labor management in that it encouraged day-to-day hiring, deterred transfer to other mines, and tightened control against unsavory outsiders, in addition to entrusting wage hike disputes and saving on expenses. On the other hand, it also had disadvantages such as being susceptible to exploitation by intermediaries, an inability to secure high-quality workers, an inability to adopt modern systems like employment or injury assistance, and fomenting labor disputes.” Thus, it would appear that the shift to direct control improved the quality of workers, which in turn led to higher retention rates. The fact that the Meiji mines decided to begin offering service bonuses around 1907 seems to be linked with this state of affairs.

3. Mine Worker Wages and Labor Supply and Demand

The First Period and Second Period are separated by the First World War. This turning point was marked by the inflation and labor shortages resulting from the Great War, as well as the subsequent labor surplus and then repeated labor shortage during wartime.

First of all, I would like to take a look at the wages offered by Japan’s major collieries around the country according to numbers from 1916. These figures have several features that stand out.

- Wages in Hokkaidō and Jōban were higher than wages in Kyushu, especially for face workers.

- Looking at each region, there do not appear to be any significant differences between the major companies and others in either Hokkaido or Kyushu. This phenomenon is also evident in the Kōfu taigū jirei from the first decade of the twentieth century.

- In Kyushu, the wages at the large coal fields of the Mitsui and Mitsubishi mines are in fact lower than elsewhere.

These facts indicate that at the time, alleged wage disparities due to company size had not yet been established. Rather, regional wage disparities seem to have been the most decisive factor. The period around 1916 seems to have been a stage immediately prior to the increase in colliery wages due to the boom resulting from the war. These figures should therefore be understood in the sense of being a starting point for subsequent labor movements and labor management.

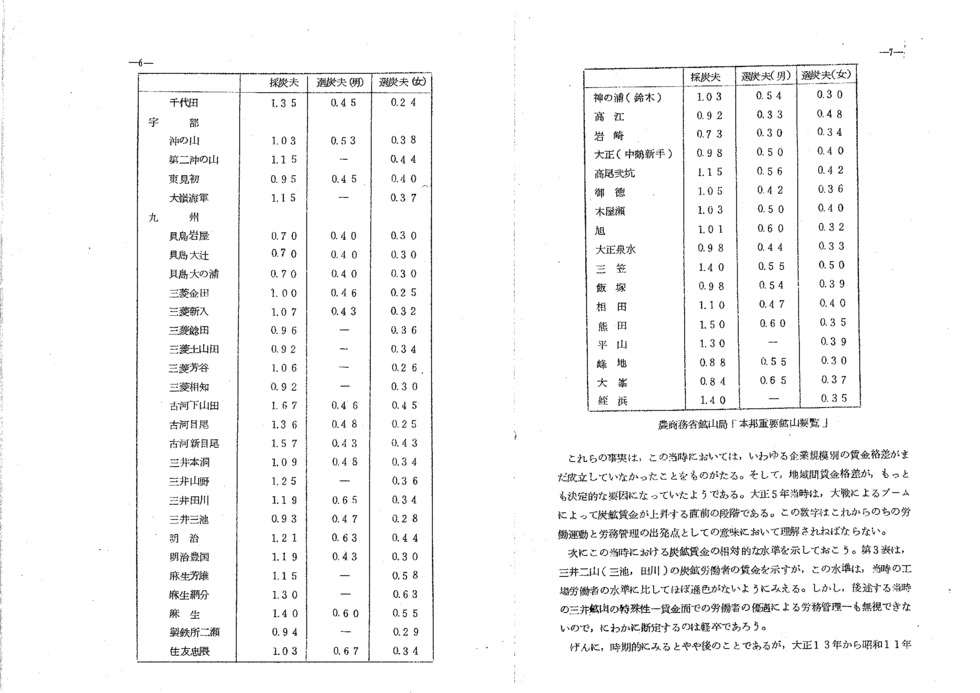

Wages at Major Collieries in 1916 (yen and sen)

|

Face worker |

Dressers (Men) |

Dressers (Women) |

||

|

Hokkaidō |

||||

|

Leading Firms |

Hokutan Yūbari |

1.4 |

0.43 |

0.31 |

|

Hokutan Mayachi |

1.65 |

0.46 |

0.32 |

|

|

Mitsui Noborikawa |

1.75 |

0.38 |

0.3 |

|

|

Mitsubishi Ōyūbari |

1.38 |

— |

0.28 |

|

|

Mitsubishi Bibai |

1.3 |

0.56 |

0.38 |

|

|

Hokutan Horonai |

1.14 |

0.46 |

0.24 |

|

|

Hokutan Sorachi |

1.55 |

0.57 |

0.32 |

|

|

Hokutan Ikushunbetsu |

1.37 |

0.47 |

0.27 |

|

|

Other |

Shin-Yūbari |

1.34 |

0.56 |

0.27 |

|

Ponbetsu |

1.46 |

0.8 |

0.33 |

|

|

Monju |

0.85 |

— |

0.32 |

|

|

Utashinai |

1.54 |

— |

0.23 |

|

|

Kami-Utashinai |

2.01 |

1.1 |

— |

|

|

Jōban |

Iriyama |

1.5 |

0.47 |

0.35 |

|

Uchigō (Iwaki) |

1.63 |

0.47 |

0.3 |

|

|

Furukawa-Yoshima |

1.8 |

0.55 |

0.22 |

|

|

Sumidagawa |

1.4 |

0.46 |

0.26 |

|

|

Dai-Nippon Taira |

1.75 |

— |

0.39 |

|

|

Onoda (Iwaki) |

1.5 |

0.48 |

0.25 |

|

|

Ōjiro |

1.8 |

— |

0.32 |

|

|

Ibaraki Muentan |

1.44 |

— |

0.3 |

|

|

Dai-Nippon Hara |

1.73 |

0.52 |

0.29 |

|

|

Shigeuchi |

1.23 |

0.39 |

0.15 |

|

|

Dai-Nippon Takahagi |

1.45 |

— |

0.28 |

|

|

Chiyoda |

1.35 |

0.45 |

0.24 |

|

|

Ube |

Okinoyama |

1.03 |

0.53 |

0.38 |

|

Dai-ni Okinoyama |

1.15 |

一 |

0.44 |

|

|

Higashimizome |

0.95 |

0.45 |

0.4 |

|

|

Ōmine Kaigun |

1.15 |

— |

0.37 |

|

|

Kyushu |

Kaijima Iwaya |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

|

Kaijima Ōtsuji |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

|

|

Kaijima Ōnoura |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

|

|

Mitsubishi Kanada |

1 |

0.46 |

0.25 |

|

|

Mitsubishi Shinnyū |

1.07 |

0.43 |

0.32 |

|

|

Mitsubishi Namazuta |

0.96 |

— |

0.36 |

|

|

Mitsubishi Kamiyamada |

0.92 |

— |

0.34 |

|

|

Mitsubishi Yoshitani |

1.06 |

— |

0.26. |

|

|

Mitsubishi Ōchi |

0.92 |

— |

0.3 |

|

|

Furukawa-Shimoyamada |

1.67 |

0.46 |

0.45 |

|

|

Furukawa-Shakanō |

1.36 |

0.48 |

0.25 |

|

|

Furukawa-Shinshakanō |

1.57 |

0.43 |

0.43 |

|

|

Mitsui Hondō |

1.09 |

0.48 |

0.34 |

|

|

Mitsui Yamano |

1.25 |

一 |

0.36 |

|

|

Mitsui Tagawa |

1.19 |

0.65 |

0.34 |

|

|

Mitsui Miike |

0.93 |

0.47 |

0.28 |

|

|

Meiji |

1.21 |

0.63 |

0.44 |

|

|

Meiji Hōkoku |

1.19 |

0.43 |

0.3 |

|

|

Aso Yoshio |

1.15 |

— |

0.58 |

|

|

Aso Tsunawaki |

1.3 |

— |

0.63 |

|

|

Aso |

1.4 |

0.60 |

0.55 |

|

|

Seitetsusho Futase |

0.94 |

— |

0.29 |

|

|

Sumitomo Tadakuma |

1.03 |

0.67 |

0.34 |

|

|

Kōnoura (Suzuki) |

1.03 |

0.54 |

0.3 |

|

|

Takae |

0.92 |

0.33 |

0.48 |

|

|

Iwasaki |

0.73 |

0.3 |

0.34 |

|

|

Taishō (Nakatsuru Arate) |

0.98 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

|

|

Takao Nikō |

1.15 |

0.56 |

0.42 |

|

|

Gotoku |

1.05 |

0.42 |

0.36 |

|

|

Koyanose |

1.03 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

|

|

Asahi |

1.01 |

0.6 |

0.32 |

|

|

Taishō Sensui |

0.98 |

0.44 |

0.33 |

|

|

Mikasa |

1.4 |

0.55 |

0.5 |

|

|

Iizuka |

.0.98 |

0.54 |

0.39 |

|

|

Aida |

1.1 |

0.47 |

0.4 |

|

|

Kumada |

1.5 |

0.6 |

0.35 |

|

|

Hirayama |

1.3 |

— |

0.39 |

|

|

Mineji |

0.88 |

0.55 |

0.3 |

|

|

Ōmine |

0.84 |

0.65 |

0.37 |

|

|

Meinohama |

1.4 |

— |

0.35 |

|

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce Mining Bureau. Honpō jūyō kōzan yōran [List of Important Mines in Japan]

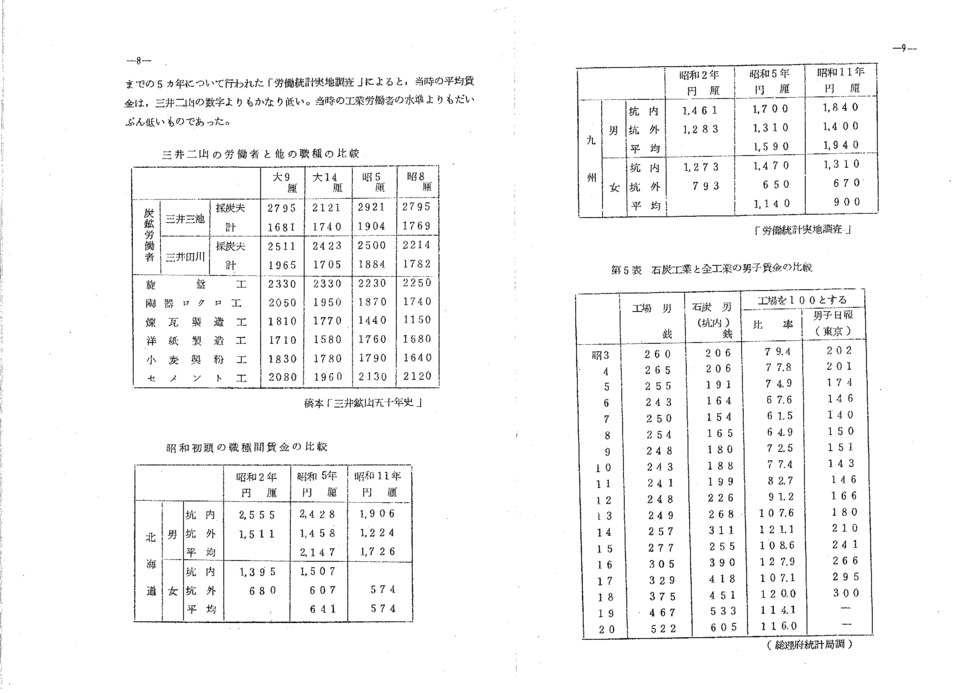

Next, let me show the relative levels of colliery wages during this period. Table 3 shows the wages of mine workers at two Mitsui mines (Miike and Tagawa), which appear to be comparable with that of factory workers for the same period. However, since, as I describe below, we cannot ignore the peculiarities of the Mitsui mines during this period—i.e., labor management by providing workers with preferential treatment in terms of wages—it would be imprudent to draw any conclusions too quickly.

Actually, according to the Labor Statistics Field Survey conducted for five-year periods between 1924 and 1936 (admittedly slightly later than the period in question), average wages at the time were quite a bit lower than the figures for these two Mitsui mines. And they were considerably lower than the level of wages earned by contemporary factory workers.

Table 3: Comparison of Workers at Two Mitsui Mines with Other Types of Occupation

(Units: rin)

|

1920 |

1925 |

1930 |

1933 |

|||

|

Mine worker |

Mitsui Miike |

Face worker |

2,795 |

2,121 |

2,921 |

2,795 |

|

Total |

1,681 |

1,740 |

1,904 |

1,769 |

||

|

Mitsui Tagawa |

Face worker |

2,511 |

2,423 |

2,500 |

2,214 |

|

|

Total |

1,965 |

1,705 |

1,884 |

1,782 |

||

|

Lathe operator |

2,330 |

2,330 |

2,230 |

2,250 |

||

|

Pottery turner |

2,050 |

1,950 |

1,870 |

1,740 |

||

|

Brickmaker |

1,810 |

1,770 |

1,440 |

1,150 |

||

|

Paper maker |

1,710 |

1,580 |

1,760 |

1,680 |

||

|

Wheat flour miller |

1,830 |

1,780 |

1,790 |

1,640 |

||

|

Cement worker |

2,080 |

1,960 |

2,130 |

2,120 |

||

Mitsui kōzan gojūnenshi [A Fifty-year History of the Mitsui Mining Company] (manuscript)

Table 4: Comparison of Wages for Different Occupations in the Early Showa Period

(Units: rin)

|

|

1927 |

1930 |

1936 |

||

|

Hokkaidō |

Men |

underground |

2,555 |

2,428 |

1,906 |

|

surface |

1,511 |

1,458 |

1,224 |

||

|

average |

|

2,147 |

1,726 |

||

|

Women |

underground |

1,395 |

1,507 |

|

|

|

surface |

680 |

607 |

574 |

||

|

average |

|

641 |

574 |

||

|

Kyushu |

Men |

underground |

1,461 |

1,700 |

1,840 |

|

surface |

1,283 |

1,310 |

1,400 |

||

|

average |

|

1,590 |

1,940 |

||

|

Women |

underground |

1,273 |

1,470 |

1,310 |

|

|

surface |

793 |

650 |

670 |

||

|

average |

1,140 |

900 |

|||

Rōdō tōkei jicchi chōsa [Labor Statistics Field Survey]

Table 5: Comparison of Men’s Wages in the Coal Industry versus Factory Labor in General

|

|

Factory laborer (sen) |

Coal miner (underground) (sen) |

Assume factory labor as 100% |

|

|

Proportion |

Male day-laborer (Tokyo) |

|||

|

1928 |

260 |

206 |

79.4 |

202 |

|

1929 |

265 |

206 |

77.8 |

201 |

|

1930 |

255 |

191 |

74.9 |

174 |

|

1931 |

243 |

164 |

67.6 |

146 |

|

1932 |

250 |

154 |

61.5 |

140 |

|

1933 |

254 |

165 |

64.9 |

150 |

|

1934 |

248 |

180 |

72.5 |

151 |

|

1935 |

243 |

188 |

77.4 |

143 |

|

1936 |

241 |

199 |

82.7 |

146 |

|

1937 |

248 |

226 |

91.2 |

166 |

|

1938 |

249 |

268 |

107.6 |

180 |

|

1939 |

257 |

311 |

121.1 |

210 |

|

1940 |

277 |

255 |

108.6 |

241 |

|

1941 |

305 |

390 |

127.9 |

266 |

|

1942 |

329 |

418 |

107.1 |

295 |

|

1943 |

375 |

451 |

120 |

300 |

|

1944 |

467 |

533 |

114.1 |

— |

|

1945 |

522 |

605 |

116 |

— |

Source: Sōrifu Tōkeikyoku Shirabe [Survey by the Statistics Bureau, Prime Minister's Office, Japan]

However, the relative status of colliery wages changed considerably over this time. Namely, when we compare men’s wages for coal mining with the average of (men’s) factory wages as a whole for the period around 1928 (which can also generally be confirmed from the Labor Statistics Field Survey for 1924), we find the following facts.

- The decrease in coal industry wages during the period of recession prior to 1932 took place more rapidly than in factory wages, such that coal’s wage ratio relative to factories fell from 80 to 60. Whereas factory wages fell by around 10%, coal industry wages fell by as much as 25%.

- Coal wages increased rapidly after 1932. Coal’s relative wage ratio rose sharply to 91 in 1937, 108 in 1938, and 121 in 1939.

- Next, comparing coal industry wages with those of urban day-laborers (in Tokyo), we find an extremely close relationship between the two during the period when wages are low. Between 1928 and 1932, both the speed and degree of wage decrease for both groups could be described as very similar. However, once coal wages begin to demonstrate a remarkable rebound after 1933, this similarity disappears.

So, then, what do these facts show us?

Labor in the coal industry is essentially manual labor, requiring relatively little skill. The labor force was previously migratory by nature, and thus characterized by a strong inherent mobility. These two facts continued to be apparent after the First Period. Since this meant that it was relatively easy for coal-mining capital to cut its workforce when the recession made it necessary to rationalize, the collieries tended to rely on this easy path. This is one factor behind the ease with which wages were cut. It is also noteworthy how the workforce reductions were implemented. I use the term workforce reduction, but in the case of the coal industry, as shown in Table 6, the number of new hires in a given year is almost equivalent to the size of the workforce, and the number of dismissals is almost the same. Therefore, it would likely have been easier to cut wages by offering lower wages to new hires from the start.

Conversely, however, it would have been necessary to show high wages in order to recruit new workers when times were booming, and it seems that we may find therein a reason for the remarkable fluctuations we see in the coal industry in this period.

In the factories, worker mobility does not appear to have been so remarkable. Accordingly, the decline in wages was not so striking even during the recession, and we can say in turn that the wage increase during the recovery was also slight. In schematic terms, then, it would seem likely that we can make the following comparison.

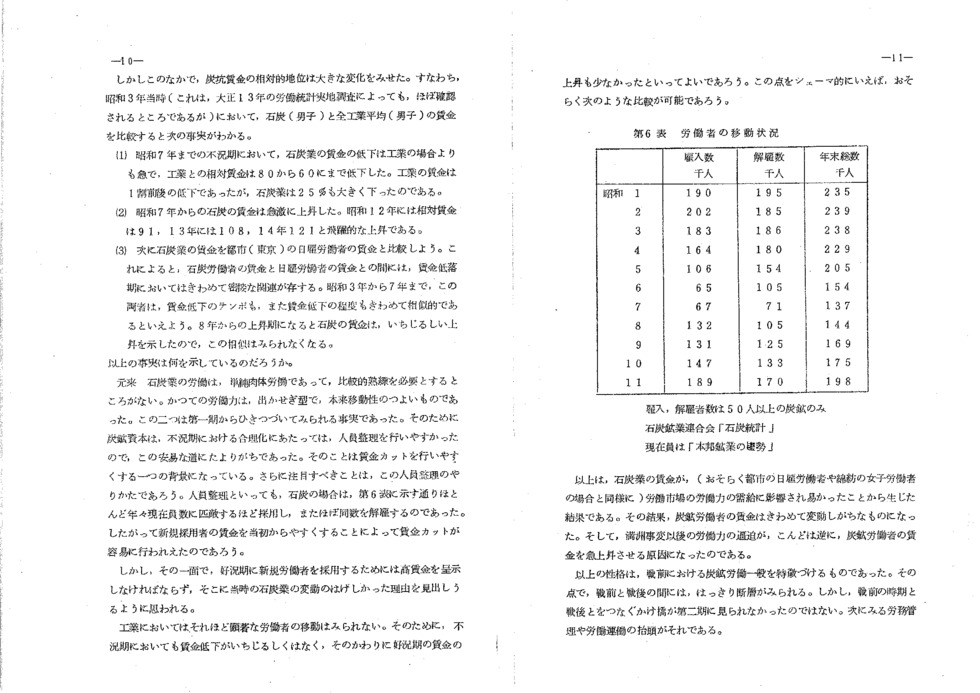

Table 6: Workforce Turnover

|

Number of hires |

Number of dismissals |

Number of employees at the end of the year |

|

|

(1,000 people) |

(1,000 people) |

(1,000 people) |

|

|

1926 |

190 |

195 |

235 |

|

1927 |

202 |

185 |

239 |

|

1928 |

183 |

186 |

238 |

|

1929 |

164 |

180 |

229 |

|

1930 |

106 |

154 |

205 |

|

1931 |

65 |

105 |

154 |

|

1932 |

67 |

71 |

137 |

|

1933 |

132 |

105 |

144 |

|

1934 |

131 |

125 |

169 |

|

1935 |

147 |

133 |

175 |

|

1936 |

189 |

170 |

198 |

The figures for hires and dismissals include only those from mines employing at least 50 people

Source: “Coal Statistics” published by the Coal Mining Federation (Sekitan kōgyō rengōkai)

Number of employees from Honpō kōgyō no sūsei [Japanese Mining Trends]

This is the result of wages in the coal industry being susceptible to labor market supply and demand (most likely as in the case of women who worked spinning cotton and day-laborers in the cities). As a result, mine worker wages became extremely volatile. Accordingly, the pressure on the labor force in the wake of the Manchurian Crisis in turn triggered a surge in mine worker wages.

This character was characteristic of colliery labor in general before the Second World War. In that respect, a clear fault line is evident between the pre-war and post-war periods. However, this not to say that a bridge linking these two periods is not apparent in the Second Period. This came as the emergence of labor management and labor movements, as we shall see next.

4. Establishment of Labor Management

Next, as a characteristic feature of the Second Period we must acknowledge the rise of labor movements after 1918 and the resulting establishment of labor management to address the former. Although this reflected the specific conditions after the 1918 rice riots, it is also an essential index dividing the First and Second Periods and serves at the same time as a bridge between the Second Period and the Third Period after the Second World War.

Here I would like to use the cases of Mitsui Miike and the Matsushima mine (also belonging to Mitsui) as examples showing the history of such labor movements. These lucidly show the form taken by labor movements at the time and the inevitability of labor management. (The following excerpts are taken from the manuscript for Mitsui kōzan gojūnenshi [A Fifty-year History of the Mitsui Mining Company]):

- Manda Coal Pit Riot (September 1918)

In the summer of 1918, when rice riots erupted all across Japan, the same wave also hit the Miike collieries. That is, since the price of third-class rice, which had been 12 sen in 1914 had risen to 37 or 38 sen, demands for wage increases were issued one after another at the zinc factory between August 23 and 29, at the Takaura pit on August 27, at the Katsudachi pit on September 1, and at the electrochemical factory on September 2, resulting in an increasingly hostile atmosphere, but ending in a lull in each case. But the company had already prepared for the worst by contacting the governor, the police, and the headquarters of the local army division. Nevertheless, on September 4, when someone at the Manda pit accused the company of tampering with the scales when inspecting the coal boxes, approx. 30 to 40 miners rioted, wielding pickaxes and throwing rocks to break windows in buildings including the First Pit Inspection Site and Second Pit Stanby Site, as well as destroying other equipment. On September 5, the riot was finally quelled by soldiers mobilized from the garrison at Kurume. In this case, the conditions for the resolution of tensions included improvements to the coal inspection regulations, improvements to medical facilities, and improvements to daily commodity sale.

Although a labor union that amounted to an industrial worker’s association was established after this incident in 1919, this organization was dissolved by the company, which created a new union, the Kyōai Kumiai, to engage in labor-management coordination.

- Miike General Labor Dispute (May and June 1924)

A dispute arose centering on Miike manufacturing plants. While the direct causes included dissatisfaction with the Kyōai Kumiai over wage increases and improvements to the coal inspection regulations, tensions eased temporarily in anticipation of a raise to be offered on June 1. When the raise did not meet expectations, however, the dispute resurfaced, lasting from June 3 until July 7, when it was finally resolved through mediation by the mayor.

- Matsushima Kōjōkai Dispute (October 1926)

This dispute arose at the Matsushima colliery, which still used the old “mine-dormitory system” (naya seido). When the payment of individual wages resulted in a loss of income to foremen (ōnayagashira) in charge of the dormitories (naya) and their personally appointed deputies (chūnayagashira), the disgruntled chūnayagashira joined with other mine workers to form a union called the Kōjōkai to launch a labor dispute. Although the ōnayagashira remained hostile to the union during this time, they subsequently invited the labor movement leader Hitoshi Imamura from Nagasaki, after which the ōnayagashira also took the side of the union, issuing petitions and the like such that the situation changed completely. Finally, the company raised wages, later going so far as to introduce conditions such as agreeing not to move to dismiss workers so easily.

As evidenced by these three disputes, the labor movement at the end of the Taishō period eventuated a significant disruption for coal capital. Companies began organizing unions like the Yūai Kumiai (“amity union”) one after another—the Hokutan Isshinkai is one such example—in an attempt to create cooperative organizations in the form of unions.

More important, however, is the emergence during this period of a prototypical form of labor management. The negative effects of the naya seido as seen at the Matsushima colliery began to be recognized from the end of 1890s, when the naya seido was discontinued in the Chikuhō district by both Mitsubishi and Mitsui, which moved to bring miners under their direct control. However, in each case it took a long time for the completion of this transition to take place. At Mitsui Tagawa, for example, abolition began in 1900 and was more or less completed by 1902, but registered contractors (ukeoi meiginin) remained until finally being abolished in 1930. Also, at Mitsui Yamano, officials known as “mine-dormitory stewards” (naya sewayaku) put in place after 1901 were only abolished in conjunction with the establishment of the Kyōaikai union in 1920.

Along with the abolition of the old systems, as described above, another consequence of the rise of the labor movement was the demand for the removal of “coal-miner supervisors” (kōfu-gakari). Until around 1918 or 1919, kōfu-gakari “were a completely company-oriented system”—“the job of kōfu-gakari was chiefly responsible for watching for attempted flight by miners, guarding against poaching of workers by other mines, forcing miners to work, and policing morality” (Mitsui kōzan gojūnenshi). However, after the emergence of the labor issue, they were tasked with the additional duty of guarding and forcibly suppressing disputes. When older kōfu-gakari were unable to do this work, the duty was gradually given to younger employees that had graduated from university. At the same time, since it was impossible to achieve their desired end through mere coercion, a method known as shidō aigo (“instruction and protection”) gradually began to be used in which all pit workers began to be accommodated in company housing, or the personal character of each individual would be investigated and then brought up for discussion. Here we see the launching point for labor management. After the Miike General Labor Dispute at the Mitsui colliery in 1924, labor supervisors were put in place at each site, as well as a provisional research division at the head office, where the study of labor management began to take place in earnest.

The Hokutan shichijūnenshi [Seventy-year History of the Hokkaido Steamship and Colliery Company] includes an essay by Hajime MAEDA reminiscing about labor management at the time. In this essay, he describes how Mitsui was able to draw on its abundant reserves of funds to provide its pit workers with preferential treatment in terms of wages and welfare facilities, while Mitsubishi implemented strict “police-style” labor management and Hokutan managed its workers with compassion because it was short of ready funds. In the large companies, in any case, it is well known that the launch of labor management tended to place an emphasis on wages and welfare facilities. On the other hand, this could also be regarded as the cause of the wage gap that finally began to emerge between large companies and the smaller and mid-sized companies. Also, despite the high turnover rate of the workers in general, this shows that some large companies began to focus on the retention of workers, encouraging them to continue working.

These facts began to take on definite shape during the Second World War. This is worth noting as a characteristic feature of the Second Period.

5. Postwar Control Mechanisms

I would like to take up the course taken after the war as a Third Period. The biggest characteristic of this period is the settlement of mine workers at collieries, the change in their quality, and the establishment of labor movements.

That is, as has frequently been mentioned, the composition of the workforce, which had consisted mainly of laborers from rural backgrounds, changed dramatically with the recruitment of conscripted workers during the war, and the arrival in the mines of demobilized soldiers and unemployed men after the war. For example, looking at a survey of previous jobs held by workers conducted in March 1949, the proportion of respondents originally from the farming, forestry, and fisheries industries or the mining industry amounted to less than 50%, while the rest came from the industrial and commercial sectors. Also, in terms of academic background, higher elementary school (junior high school) graduates now accounted for two-thirds of employees (Sekitan sōgi [Coal Disputes], p. 35).

This was a major factor that strengthened the labor unions at the collieries after the war. In addition, many urbanites no longer had homes to return to. These people had a strong incentive for trying to settle permanently at the collieries. Many people had also been involved previously in the labor union movement in the cities or in the collieries in the past, and in many cases these people became leaders in the establishment of unions after the war. Examples of such individuals include Takashi Mizutani at Mitsubishi Bibai and Tsunekatsu Yamamoto at Nittan Takamatsu. Of course, after the abolition of controls in 1949, the companies once again attempted to shift back to rural villages as the source of their labor. For example, this is demonstrated by the fact that among the workers at Kaijima Ōnoura, 47% of employees who joined the company between 1948 and 1952 came from rural backgrounds, a higher proportion than in any other cohort. However, with the current strengthening of the unions, the fact that they are workers notwithstanding, it is no longer permissible to equate them with the highly mobile rural workers of the past. This is because there are guarantees by the union, which presents difficulties for changing jobs.

In addition to these changes in conditions for workers, coal prices had also been controlled by the state from wartime into the post-war period. In particular during this period, because the increase in coal production was regarded as the key to the economic world, and also because the increase in production resulting from the massive influx of labor was regarded as a paramount necessity, colliery wages had to be set at the highest level for all industries. Naturally, this measure was backed by a government guarantee, irrespective of a given company's profitability. This decision was taken in formal terms through negotiations to set a national standard carried out by the Japan Council of Coal Miners’ Unions (Tankō rōdō kumiai zenkoku kyōgikai or Tankyō) and the Japan Coal Mining Association (Nihon sekitan kōgyō renmei) in 1947 and then, after Tankyō split into two separate unions (Tanrō and Zensekitan), by parallel negotiations carried out with the Coal Mining Association from the autumn of 1947 into 1948. In practice, however, coal controls during this period were supposed to guarantee the costs of production at each mine, and it may be said that the form of nationally unified (later parallel) negotiations was taken because it was necessary that the labor costs encompassed within these should be determined uniformly at the national level. At the same time, for all that the management side claimed an industry standpoint during the collective bargaining, in fact, it planned from the beginning to pay wages to the extent that would be allowed by negotiation with the government position. To that extent, even though collective bargaining was carried out to a fierce degree, this was in fact only a stage prop to get the government to allow wages to guarantee the coal plan.

However, some facts that arose at this time that would come to have a considerable influence on the determination of colliery wages in future included the following:

- The standardization of wages at a national level

- Unified negotiations with national organizations

- The restoration of a balance with factory wages

6. Wage Determination after the Abolition of Controls

As seen above, a transformation was engendered in the wage-determination mechanism that had been created during the period of postwar control. Next, I would like to consider how this affected wage-determination mechanism after the era of control.

The first thing to be considered is the fact that the standardization of wage levels in the major coal companies was maintained even after the abolition of controls. Naturally, since this was opposed by the Japan Coal Mining Association, it seemed that the unified format of negotiations would be done away with, as with the negotiations with individual companies that took place in 1949 and 1951. However, after the re-election of the executive in the spring of 1952, Tanrō underwent its so-called “Left Turn,” which led to the establishment of a form of organized central negotiations, or of “diagonal” negotiations that continues to this day.

This form can be said to be the most uniform among Japan’s major industries. This is because of the tradition that was left behind by the post-ward coal controls. Of course, the differences in accounting details between companies and the framework of the company unions have also be seen to have distorted the unified negotiations in some sense, but Tanrō has been able to overcome these differences to maintain wage uniformity. This may be said to be one of the basic conditions for the determination of coal wages.

When determining wages through unified negotiations, management will present wages using the standard based on a company with the poorest performance within a group of companies. The unions, on the other hand, will request wage increases based on average or better-than-average firms. And the fact that this has resulted in a considerable gap between the two perspectives, and so served as the cause of fierce disputes, seems undeniable.

The next thing to consider is the recession faced by the coal industry. This has frequently resulted in workforce reduction issues, and the crisis continues to grow even now. These conditions have adversely affected company performance, and the level of union demands has also tended to be lower than in other industries. While it could be said that herein lies one of the limitations of the union movement, in addition we could also say that it has now become clear that companies have been unable to keep abreast of the widespread transformations in production conditions.

In other words, this is because although the coal recession has in some ways arisen as a result of natural or extrinsic conditions, beyond these, there are also many ways in which it should be considered to have been brought about as a result of managements’ failure to undertake any essential changes to the labor-intensive capital-saving production methods employed in the past. And it also seems to be the case that the biggest adjustment measure that it was once able to draw upon – i.e., the expansion and contraction of the workforce – has been hobbled by union resistance, which has only served to aggravate the symptoms of arteriosclerosis. However, regardless of its cause, there seems little doubt that the coal recession is once again causing a relative decline in coal wages.

This document constitutes a part of the results of the research project entitled “A Study of Wage Fluctuations and Influences by Industry” commissioned in fiscal 1959 by the Japan Institute of Labor.

The paper was prepared by Takafusa Nakamura.

[1] In 1906, the daily charge for board for those living in camps or dormitories was as follows:

“While charges vary from place to place, in many cases they are around 22 or 23 sen per day. In addition, at the Miike and Meiji collieries:

- At the Miike colliery, unmarried workers lodging in the dormitories are boarded directly by the mine. Those with less than a year of service are charged 16 sen, those with over a year of service 15 sen, and those with over three years of service 13 sen and 5 rin.

- At the Meiji colliery, board for unmarried men is set at 22 sen per day, while a 2 sen subsidy per day is supplied by the mine operator.”

Source: Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce. 1957. Kōfu taigū jirei [Case Studies of Mine Worker Treatment] Kyūshū sangyō shiryō kenkyūkai [Kyushu Industrial Historical Materials Study Group] (facsimile edition), pp. 85–86.