Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

History of Nippon Steel Corporation

Since its establishment until the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the operation of Nippon Steel Corporation was in line with the national policy for the steel industry and excelled in terms of production, expansion of facilities and supply for demand. At the 8th annual shareholders’ meeting on December 23, 1937, Chairman Hirao said:

“Allow me to outline our results for this period. We continued to strive to increase production at blast furnaces, steelmaking and rolling facilities, and other facilities at full capacity. At the same time, our facilities expanded. Although many employees joined the armed forces due to the outbreak of the war and we experienced other effects, production exceeded the level in the previous period. […] In response to the situation, we strove to expand our production capacity as far as possible and increased supply in response to sharply increasing demand. Currently, we are endeavoring to stabilize steel prices by improving our distribution.”

As the war expanded, it became difficult to continue the favorable development due to the limited supply of materials for construction and labor, in particular the shortage of skilled workers from 1938. At the 12th shareholders’ meeting on December 21, 1939, Chairman Hirao said:

“We continued to endeavor to expand production at blast furnaces, steelmaking and rolling facilities, and other facilities at full capacity during this period, but we experienced greater operational difficulty than in the previous period mainly due to the shortage of labor as well as severe water shortages and limited power supply caused by unreasonable local weather. However, we overcame the difficulty and were able to achieve fairly good results.

The new Wanishi Works, which was built under the third expansion plan, the integrated iron and steel-making facilities at the Hirohata Works, which were built under the fourth expansion plan, and the construction of iron-making facilities at the Seishin Works, which is being built under the fifth expansion plan, were affected by the shortages of materials for construction work and labor. However, we strove to continue the construction work. At the Hirohata Works and the Wanishi Works, the initial firing of a blast furnace was successfully completed on October 15 and December 15, respectively.

This allows us to expand production, and we are deeply committed to expansion work in other locations. Nonetheless, I think more difficulties lie ahead due to the situation I have just described.”

Chairman Hirao stated that new full-scale plant facilities, including those at the Nakamachi plant in Wanishi and the Hirohata Steel Works, finally started to operate and the company was about to take the first step toward strong production, but at the same time, it faced difficulties with implementing the remaining construction work and the shortage of labor.

In April 1938, as it is well known, the National General Mobilization Act was promulgated and came into force in May. The purpose of the act was to control and manage human and material resources to use all national capabilities most effectively to accomplish the war objectives. The act gave the government the authority to mainly do the following in relation to labor:

- i) Recruit people as long as it did not interfere with conscription

- ii) Make people, companies and other organizations cooperate with national or local public entities

iii) Regulate the use, hiring and dismissal of employees, wages and other work conditions

- iv) Prevent or resolve labor disputes and restrict or prohibit acts related to labor disputes

- v) Request that people to report their vocational skills and experience and examine them

- vi) Order factories, a variety of training institutes and schools to force skilled workers to enhance their skills

The National General Mobilization Act became a basic law for managing labor from the Second Sino-Japanese War to the Pacific War. Under the legal authority of the act, a series of labor control regulations (primarily for hiring skilled workers) were made: the school graduates use limitation ordinance (enacted in August 1938), the national vocational skills declaration ordinance (January 1939), the employees hiring restriction ordinance, skilled workers training ordinance, wages control ordinance (March 1939), and the national recruitment ordinance (July 1939). In July 1939, the Cabinet’s Planning Agency announced the wartime regime’s first labor mobilization plan, which estimated the new demand for workers in fiscal 1939 at 1.1 million people. The plan intended to survey all kinds of labor supply and establish effective labor control to achieve the following in preparation for a long war: (i) promoting war production, (ii) executing the production expansion plan, (iii) increasing exports and (iv) ensuring supplies of private consumption goods. It was developed in response to the productivity expansion plan approved by the Cabinet in December 1938, which described policies to establish 15 defense industries and basic industries, including steel, coal and light metal industries and, policies to enhance military supplies.

Nippon Steel Corporation managed labor issues during the war, controlled and driven by the government’s labor mobilization policy.

On April 1, 1939, Nippon Steel Corporation communicated to the entire company the company credo consisting of three articles in line with the general mobilization of the national spirit: (i) assistance with the emperor’s work, (ii) dedication to duties, and (iii) affiliation and cooperation. In response, industrial patriots’ groups were formed one after another. At the same time, training started on factory floors of the Yawata Steel Works under the government order to cultivate skilled workers at factories and other workplaces. Before long, the training center of the works was separated and upgraded from being under the control of the welfare section of the general affairs department to being an entity under the direct control of the director of the works. In July 1939, the first worksite managers’ meeting was held at the head office. At the meeting, the head office and each worksite exchanged opinions and coordinated countermeasures on the execution of the production capacity expansion plan and the recruitment and cultivation of employees, particularly for countermeasures against the shortage of workers and issues related to the appointment of officers, the training of skilled workers, and interactions between engineers and technicians, among other issues.

In October 1939, part of the construction work at the Hirohata Works was completed, and the initial firing of a blast furnace was completed. Before the start of operation, the Hirohata Works requested that the Yawata Steel Works train required workers and it planned to transfer workers from the Yawata Steel Works to the Hirohata Works. Consequently, according to the status of workers at the Hirohata Works in early 1941 (the end of May 1941), around 20% of its workers (3,626 workers) were skilled workers (329 workers) transferred from the Yawata Steel Works and semi-skilled workers (392 workers) who completed the contract training course at the Yawata Steel Works.

Similar steps were taken at the Wanishi Works (in particular the Nakamachi plant) and other work areas.

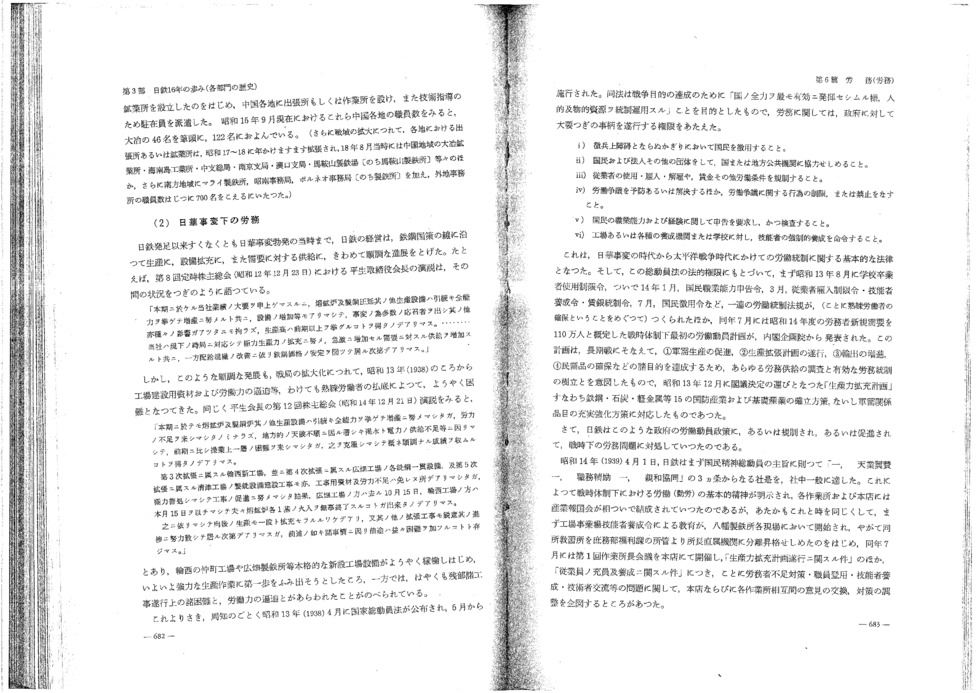

From 1939 or 1940, however, many muscular workers suitable for steel manufacturing were conscripted from the work areas, and hiring muscular workers became increasingly difficult. Many less strong, unskilled workers were hired instead, and as a result, the aptitude of workers declined gradually, which had a seriously adverse effect on labor efficiency. A breakdown of the workers at the Yawata Steel Works according to the number of years of service as of December 31, 1940, is shown in Table 5.

Table

Even at the Yawata Steel Works, which had 40 years of history as a state-run steel works since its foundation, more than half of the workers there were employed for five years or less. In fiscal 1936 (March 31, 1937), the average years of service for workers at the Yawata Steel Works (21,617 workers) was 10 years and three months, and workers who worked for five years or more accounted for 67% (labor statistics of the works). That highlights the dramatic change in the composition of workers in terms of quality during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

(3) Strengthening of labor mobilization and decline in the quality of workers

Putting quality aside, Nippon Steel almost achieved its intended objectives in terms of quantity by recruiting large numbers of the required workers from the public until 1941. The labor supply became extremely limited after the outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941.

This led to dramatic military mobilization and the number of workers decreased remarkably. As military industrialization expanded, demand rose to increase the number of workers. However, overcoming the labor shortage became more and more difficult. In addition, the number of people with technical skills was almost exhausted, which created a very narrow bottleneck to job performance. In 1942, competition to hire workers intensified in the industry. Nippon Steel strengthened the development of mid-level skilled workers at each work site, focusing on offsetting labor shortages, but failed to achieve sufficient results. Finally, in April 1942, Nippon Steel began the compulsory recruitment of workers (under the national recruitment ordinance) at the Yawata Steel Works and Hirohata Works, the two most important branches. This was the first time that any steel manufacturer had forcefully recruited workers. In the beginning, the quotas of recruited workers were 500 for the Yawata Steel Works and 450 for the Hirohata Works. (In November to December 1941, the scope of application for the national registration ordinance and the recruitment ordinance was expanded, and all men from the ages of 16 to 40 and unmarried women from the ages of 16 to 25 were within the scope of registrants. The registrants could be recruited at factories designated by the Health and Welfare Ministry. Nippon Steel’s first compulsory recruitment was inextricably linked to the government’s labor mobilization measures. The registration systems underlying the recruitment were subsequently expanded several times.)

On April 17, 1942, the Yawata Steel Works was designated as an important work site under Article 2 of the labor management at important work sites ordinance (February 24, 1942; Imperial Ordinance No. 106). The Hirohata Works (September) and other work sites became designated factories. In this way, each work site of Nippon Steel became a state-controlled factory that was managed and directly supervised by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (which became the Ministry of Munitions in November 1943) and the Health and Welfare Ministry under the National General Mobilization Act and certain laws and regulations based on the execution of the act. The link between the factories and the national policy deepened in terms of labor management. (Important work site means “factories, mines, and other places that are involved in operations related to the production or repair of general mobilization materials or transport necessary for national mobilization designated by the Minister of Health and Welfare.”)

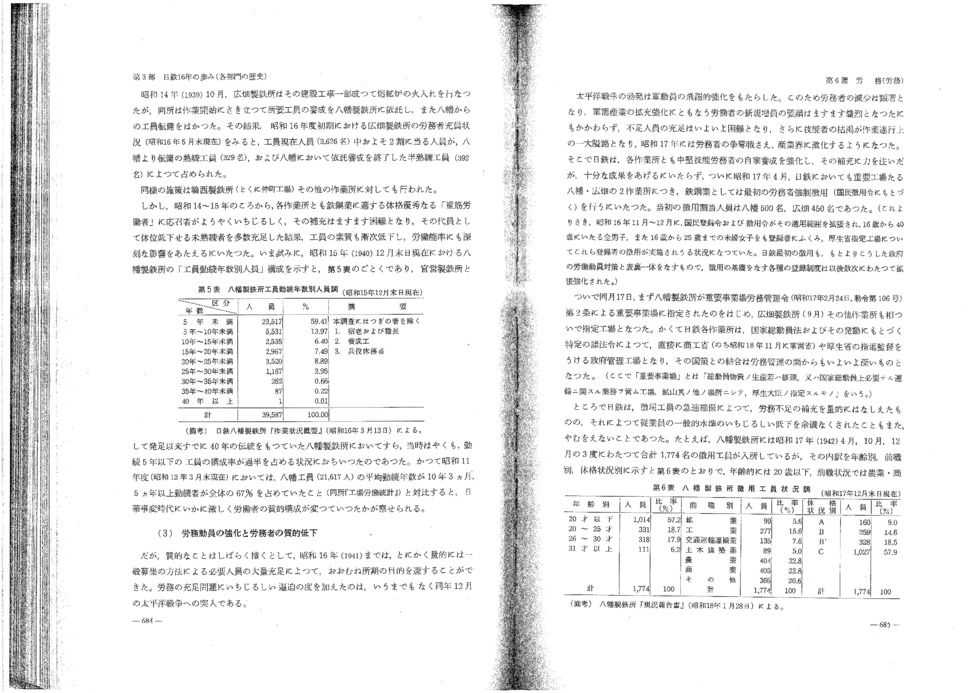

Nippon Steel overcame the labor shortage in terms of quantity by rapidly recruiting factory workers, which in turn inevitably led to a remarkable decline in the general skill level of employees. For example, a total of 1,774 workers were recruited and joined the Yawata Steel Works in April, October and December in 1942. Table 6 shows a breakdown of the workers who joined the works according to age, former job and physical constitution. The workers who were 20 years old or younger, those who formerly worked in agriculture, commerce and other sectors, and those whose physical constitution was the lowest constituted over half of all workers.

In May 1942, the Cabinet’s Planning Agency announced the first labor mobilization plan after the outbreak of the Pacific War. In the plan, the term “labor mobilization,” which was used in the past, changed to “national mobilization,” and the plan included the following statement:

“The purpose of the mobilization plan of 1942 is to make a war effort promptly, considering the current situation, and to achieve a far-reaching revolution in the people’s occupational practices. An overview of the labor situation indicates that the labor supply and demand is becoming tighter after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Considering the situation, the government has begun to strengthen its mobilization plan. This plan includes the expansion of the national registration, a revision to the labor supply and demand adjustment ordinance, and the strengthening of cooperation in the labor reporting ordinance and labor management at important work sites ordinance.”

Moreover, from 1942, all students from the age of 14 or older were mobilized regardless of their school. In 1943, the same number of Koreans were moved from Korea to Japan as in the previous year (1942), and Chinese and Koreans living in Japan, prisoners of war, and prisoners were incorporated into the plan. For labor allocation in 1943, five industries received top priority: steel, coal, aircraft, light metal and shipbuilding.

From 1942 to 1943, Nippon Steel strove to take advantage of labor sources using every means. In addition to the Yawata Steel Works and Hirohata Works, all work sites of the company in Japan (Wanishi, Kamaishi, Fuji and Osaka) recruited workers. Because this number fell short of the plan, the company endeavored to hire underage male workers and female workers while importing Korean workers en masse as special workers. At the same time, the company allowed students, women’s volunteer corps and working patriots’ corps to work in supplementary units. (Mobilized students’ dedicated efforts received a lot of praise.) Around this time, wartime captives were forced into labor at each work site by order of the authorities.

Overseas, most of the workers at the Kenjiho and Seishin Iron Works in Korea were Koreans, and after the outbreak of the war, replenishing workers was not very difficult. However, the shortage of Japanese job applicants was serious, mainly because Japanese job applicants for employment at the works decreased sharply with the emergence of Manchuria and North China. At the Kenjiho Iron Works, Koreans accounted for 82% of the workers, while Japanese accounted for 18% towards the end of December 1942. In 1943, the works attempted to replenish the number of Japanese workers, focusing on hiring discharged soldiers and Japanese trainees, among others (Kenjiho “Status Report”; February 1943). The Seishin Iron Works was in a similar situation. Replenishing the number of Japanese workers, preventing relocations and increasing attendance rates were the most urgent issues during the war (refer to Table 7).

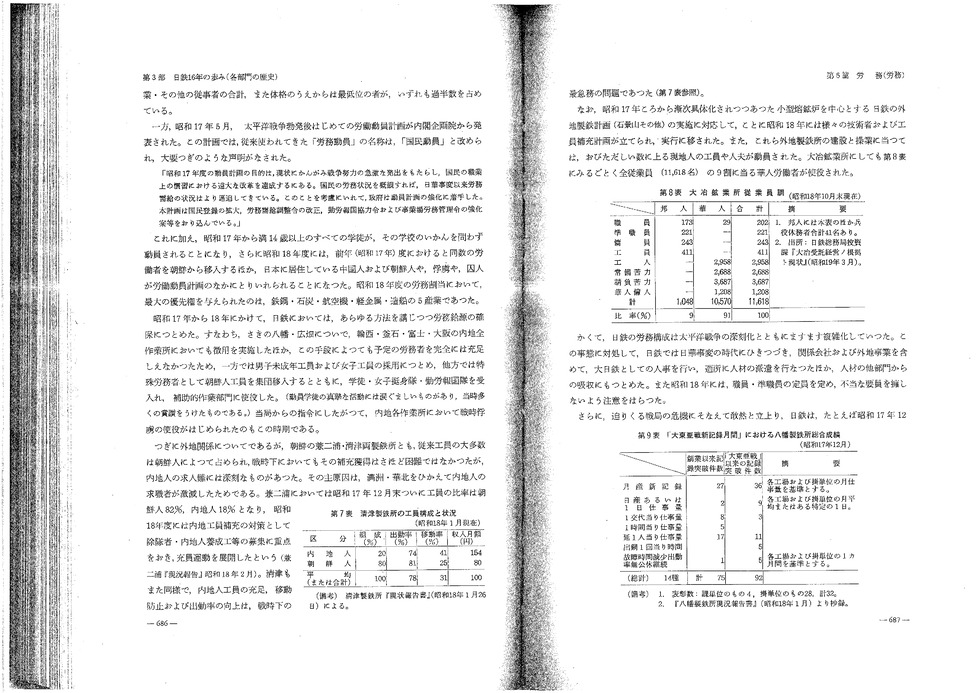

Nippon Steel’s iron manufacturing plans overseas (Sekkeizan etc.), focusing on small blast furnaces, materialized gradually from around 1942. In response to the execution of those plans, ones for replenishing the number of engineers, technicians and workers were developed and executed particularly in 1943. For the construction and operation of those steelworks overseas, vast numbers of local workers and laborers were mobilized. At the Daiya mining facility, Chinese workers accounted for 90% of all the employees (11,618 people), as shown in Table 8.

In this way, the labor structure of Nippon Steel became increasingly complex as the Pacific War intensified. Nippon Steel continued to organize its personnel as “Greater Nippon Steel,” including its affiliates and operations overseas, as it did during the period of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and assigned them to the correct positions. At the same time, it endeavored to absorb human resources from other business segments. In 1943, the company set the number of officers and sub-officers and paid attention to avoid unreasonable factors.

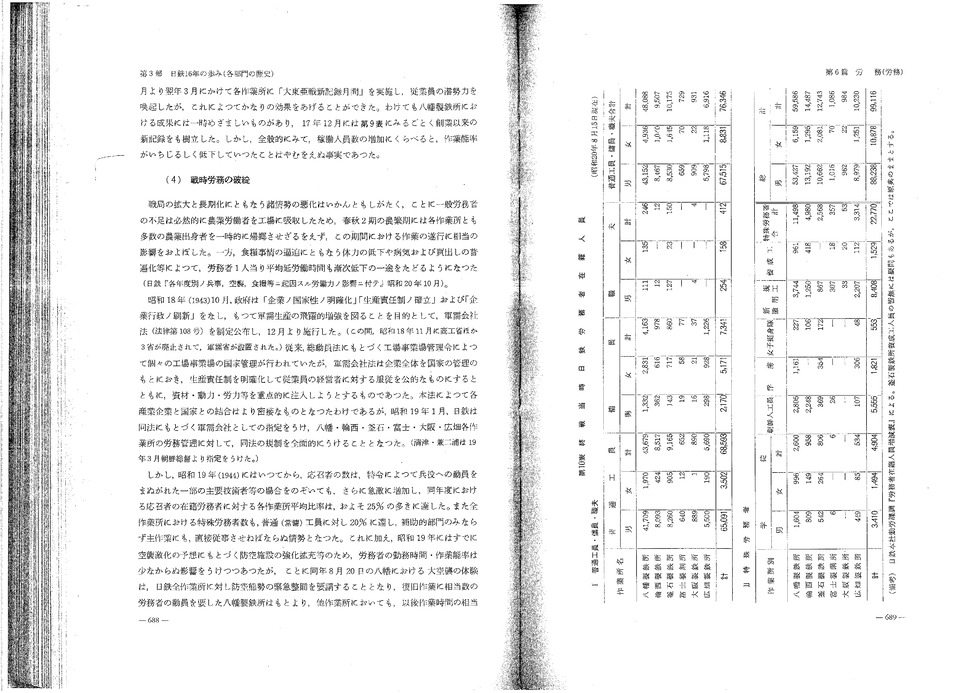

Nippon Steel faced looming crises in the war. From December 1942 to March 1943, for example, Nippon Steel launched a “Greater East Asia War record-breaking months” campaign at each work site to bring out the potential of employees and achieved considerable results. The Yawata Steel Works, in particular, temporarily displayed remarkable results. In December 1942, the works set the first record since its establishment, as shown in Table 9. However, by and large, the remarkable decline in operating efficiency was unavoidable despite the number of active workers increased.

(4) Collapse of labor during the war

The decline of the situation due to the expanded and prolonged war was out of control. The shortage of unskilled laborers naturally led to the absorption of agricultural laborers by factories and each work site was forced to allow many agricultural laborers to temporarily return home during the busy farming seasons in spring and autumn. It had a considerable effect on the execution of work during those seasons. Declining physical fitness, illness and travelling to buy food became commonplace due to the limited supply of food, which led to a gradual decrease in total work hours per worker (Nippon Steel “On Effects of Military Affairs, Air Raids, Food, Etc. on Labor by Year”; October 1945).

In October 1943, the government enacted and promulgated the Munitions Companies Act (Act No. 108) to clarify the nationality of companies, establish a production responsibility system and reform the government of companies, thereby increasing war production dramatically. The act was enforced in December. (In November 1943, three ministries, including the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, were abolished, and the Ministry of Munitions was established.) Before the Munitions Companies Act was enforced, individual industrial work sites were nationalized under the factories and other workplaces management ordinance under the National General Mobilization Act. The purpose of the Munitions Companies Act was to put all companies under the control of the state, clarify production responsibility, officiate employees’ obedience to management and focus on injecting materials, power, labor and other resources into munitions companies. Under the act, industrial enterprises and the nation became more closely connected. In January 1944, Nippon Steel was designated as a munitions company under the act, and labor control at the Yawata, Wanishi, Kamaishi, Fuji, Osaka, and Hirohata works became thoroughly regulated. (Seishin and Kenjiho were designated by the Governor-General of Korea in March 1944.)

In 1944, the number of draftees, excluding key engineers and other personnel who were exempt from the draft under a special order, increased sharply. The average ratio of draftees to workers at each work site stood at as much as 25% in 1944. The ratio of special workers to regular workers at all work sites accounted for 20%, which indicates that the special workers not only had to work in auxiliary departments but were also directly involved in the main work. In addition, in 1944, the work hours and efficiency of the workers were greatly affected by the strengthening and expansion of air defense facilities on the assumption that air raids would intensify. The large-scale air raid in Yahata on August 20, 1944, in particular, triggered an urgent improvement in air defense capabilities at all work sites of Nippon Steel. A considerable portion of the work hours were spent on taking countermeasures against air raids not only at the Yawata Steel Works, where many workers needed to be mobilized for recovery work, but also at other work sites. Under such circumstances, the technical level declined more and more, and production efficiency sharply worsened as a natural course of events.

In 1945, Japan braced for the mainland battle of the Pacific War. That year the top-priority issue was boosting food production. An emergency measure was taken to secure resources for agriculture: some of the recruited workers with experience in agriculture had to return to faming. Each work site mobilized workers to work in kitchen gardens to improve the food situation. (Around this time, some of the workers were dispatched to coal mines in response to requests for increasing coal production.) There were hardly any new labor supply sources left, and the number of engineers and technicians was not expected to increase. Even the number of recruited workers, mobilized students, members of working patriots’ corps and Korean workers was not expected to rise. Nippon Steel strove to overcome the situation temporarily by relocating workers at plants that were to be suspended or closed due to a lack of raw materials or means of transport, among other reasons. However, this emergency measure was not easily facilitated because of the confusion caused by air raids and the worsening of the situation of transport and food. A severe shortage of raw materials caused a surplus of labor in some divisions and production paralysis began. Nippon Steel was damaged in the first Kamaishi naval bombardment on July 14, 1945, the Wanishi naval bombardment on July 15, the Yahata air raid on August 8, and the second Kamaishi naval bombardment on August 9. Many employees died, were wounded or lost their homes. The employees were completely exhausted when the war ended.

(5) From the end of the war to the dissolution of Nippon Steel

The labor situation of Nippon Steel during the war has been outlined above. Due to the defeat in war, Nippon Steel lost the Kenjiho and Seishin Iron Works in southern Korea and all other facilities overseas. Table 10 shows the numbers of workers at work sites in Japan as of August 15, 1945, according to a document submitted by the homeland labor section to GHQ after the war. Nippon Steel began to reduce the workforce while it made arrangements in Japan for laying off or accepting around 20,000 employees at the Kenjiho and Seishin Iron Works and other facilities overseas. The workforce reduction and arrangements were implemented while Nippon Steel was in the process of making desperate efforts to restore steel production after the war, focusing on priority-based production and production concentration at the Yawata Steel Works.

In October 1945, the national labor mobilization ordinance, the labor management at important work sites ordinance, among other wartime labor-related ordinances, were repealed. In December, the National General Mobilization Act was also repealed. Workforce reduction after the war naturally targeted contingent workers forced to work by the national government or special workers in the table above. Subsequently, rank-and-file employees, especially those who hoped to resign, were laid off. Nippon Steel did not actively lay off regular workers to prepare for a recovery in the rate of operations and prevent the loss of skilled workers. However, when production concentration at the Yawata Steel Works started in July 1946, the other work sites shut down temporarily and the number of employees decreased gradually.

On December 1, 1947, the Employment Security Act was enacted. At the end of February 1948, the labor supply business was completely prohibited, and each work site had direct control over the hiring of workers (laborers). From the fall of 1945 to the beginning of the next year, workers’ unions or employees’ unions were formed at work sites, one after another, as described below. In April 1946, the Federation of Nippon Steel Workers’ Unions was formed. At the head office of Nippon Steel and some work sites, a labor committee or a management council was formed, which consisted of members from both management and the workers’ union, and labor agreements, pay revisions and other management issues were discussed by labor and management.

Around this time, steel production started to recover. In March 1947, the initial firing of a blast furnace after the war started at the Wanishi Works. In May 1948, Kamaishi No. 10 blast furnace was first fired. In January 1949, an order was issued to prepare for the restart of the Hirohata Works. Meanwhile, labor at each work site of Nippon Steel gradually returned to a normal state during peace time (the Osaka work site became the Osaka plant, then the Osaka office, and in 1949, was separated from Nippon Steel as Daitetsu Kogyo). In March 1950, Nippon Steel was dissolved.