Reference:Miike Labor Disputes

- Author

- Mitsui Mining Co., Ltd. (ed.)

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Vol. 1: Mitsui’s labor-management relations and labor disputes

Preface: Prewar labor management and labor disputes

Section 1: Prewar labor management and labor-management relations

- Early labor management (from establishment to around 1920)

The first buds of the modern labor movement appeared in Japan following the First Sino-Japanese War, with 32 labor disputes already occurring by late 1897. However, it was as of 1918-19 that the modern labor movement surfaced rapidly in parallel with the permeation of socialist thought. Not only did the number of labor disputes soar—to the extent that there were 417 labor disputes in 1918 and 497 in 1919—but labor union numbers too demonstrated a swift increase as of that time.

Contemporary social unrest during that period is exemplified by the nationwide rice riots. At Mitsui too, a riot broke out at the Miike coal mine’s Manda pit in 1918, finally bringing the company’s attention to labor management. Prior to that point, there was a decided lack of anything that could be described as modern labor management. This was not a situation restricted to Mitsui, however, but rather a characteristic of industry in general up until that time. Particularly in the case of coal mining, the nayagashira or “bunkhouse” system (whereby workers were not directly employed by the mining company but by subcontractors each in charge of a number of miners) was in operation from the Edo period (1603-1867) right through the Meiji period (1868-1912) and on almost to the end of the Taisho period (1912-1926), with most mines leaving the bunkhouse foreman to recruit miners, take on mining operations on a subcontract basis, and handle labor management. In other words, the bunkhouse system itself was also a labor management system.

Mitsui too used this type of system at some of its operations—Tagawa, Yamano, and Kamioka, for example—through until around 1926, and recruiting and subcontracting systems similar to the bunkhouse system existed briefly and to a minor extent at Miike too at the beginning. However, because of the substantial harm caused by the harshness of this type of system and the social criticism that it attracted accordingly, the bunkhouse system was abolished by around 1912, followed by other similar systems by around 1926.[1] Mitsui instead adopted a system of direct control, with miner recruiting, etc. all handled by the company.

In other words, as of around 1900, a labor management institution called kofukata was instituted at Mitsui’s operations (Table 1) to hire and fire miners, watch out for runaways and poaching of workers by other mines, encourage work, and enforce discipline. In addition, as of 1898, outstanding miners were appointed as caretakers, known as sewakata (at Miike) or sewayaku (at Tagawa), to manage company housing. These personnel were shifted into miners’ dormitories, where they interacted with the other miners on a daily basis, looking after both the miners’ daily welfare and company housing. Later, they were also given labor management responsibilities, such as ensuring that miners turned up to work and didn’t run away from company housing, serving a major role in communication between the company and the miners from their position midway between the two.

The caretaker system was retained even after the formation of the kyoai kumiai (factory councils) discussed below, and following the Second Sino-Japanese War, these personnel were renamed hodoin. In the case of Miike, particularly following the restructuring of the company in 1953, they were fiercely attacked by the unions as “vanguards for the control of workers’ status by capital,” but they remained in place until the system was abolished in 1954 (see Chapter 3, Vol. 2). From this it is clear how valuable the system was in terms of an institution for labor management.

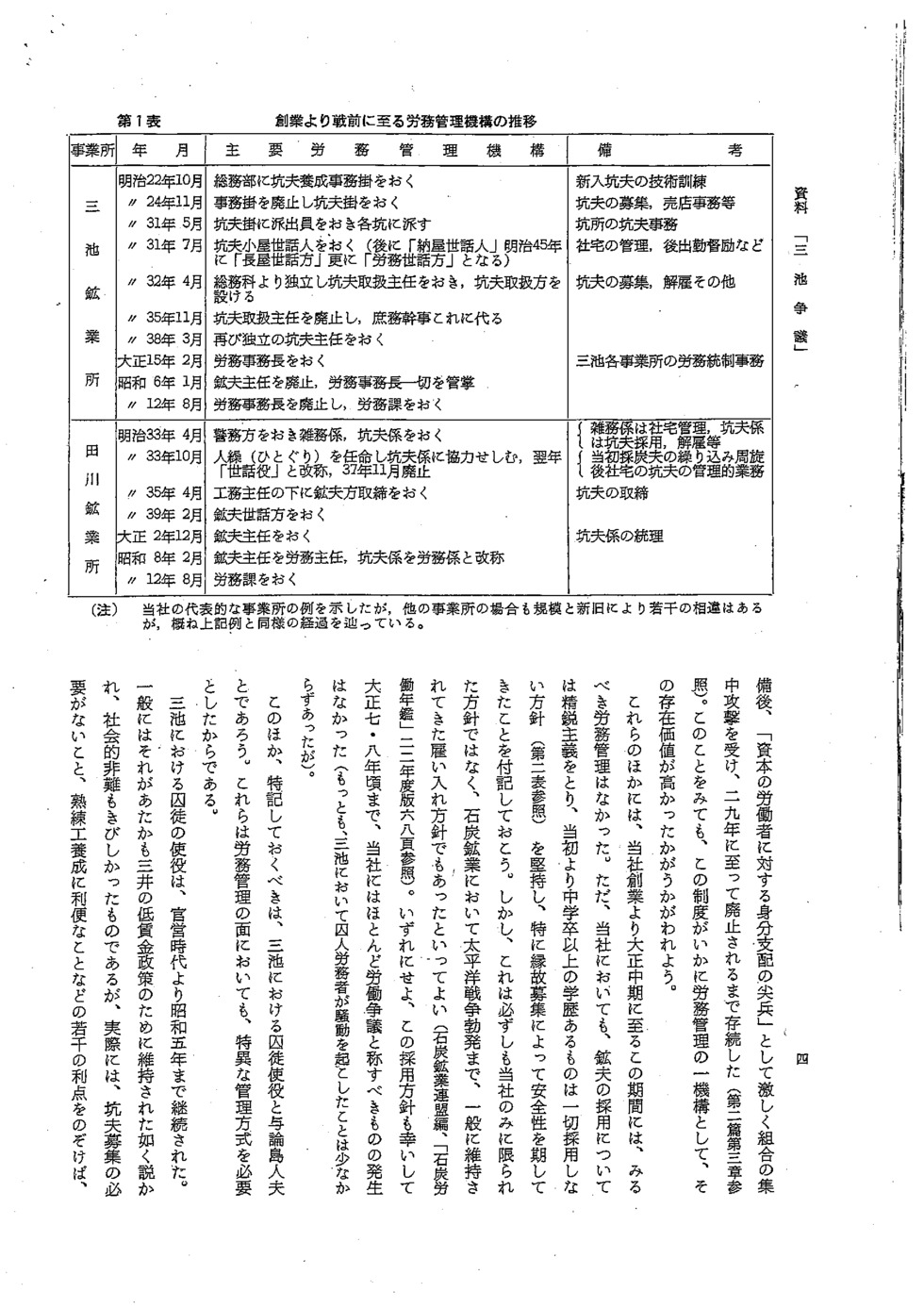

Table 1: Labor management institutions from company establishment to the prewar period

|

Operation |

Date |

Main labor management institution |

Notes |

|

Miike Kogyosho |

Oct. 1889 |

Kofu yosei jimu gakari (miner training administration desk) set up within somu bu (general affairs division) |

Technical training for new miners |

|

Nov. 1891 |

Kofu yosei jimu gakari abolished, replaced with kofu gakari (miner desk) |

Recruiting miners, store duties, etc. |

|

|

May 1898 |

Agents appointed to kofu gakari, sent out to pits |

Miner administration at pits |

|

|

Jul. 1898 |

Kofu goya sewanin (miner hut caretakers) appointed (later called naya sewanin, in 1912 nagaya sewakata, and later romu sewakata) |

Management of company housing, later encouragement of attendance, etc. |

|

|

Apr. 1899 |

Kofu toriatsukai shunin (chief in charge of miners) appointed independent of somu ka (general affairs section), along with kofu toriatsukai kata (officers in charge of miners) |

Miner recruiting and dismissal, etc. |

|

|

Nov. 1902 |

Kofu toriatsukai shunin post abolished, duties taken over by shomu kanji (general affairs director) |

|

|

|

Mar. 1905 |

Independent kofu shunin (miner chief) appointed again |

|

|

|

Feb. 1926 |

Romu jimucho (labor administration supervisor) appointed |

Labor control at the various Miike operations |

|

|

Jan. 1931 |

Kofu shunin post abolished, romu jimucho handles all affairs |

|

|

|

Aug. 1937 |

Romu jimucho post abolished, romu ka (labor section) set up |

|

|

|

Tagawa Kogyosho |

Apr. 1900 |

Keimukata appointed along with zatsumu gakari (miscellaneous affairs officers) and kofu gakari (officers in charge of miners) |

Zatsumu gakari handle company housing management, kofu gakari handle hiring and firing of miners, etc. |

|

Oct. 1900 |

Hitoguri (labor dispatchers) appointed to cooperate with kofu gakari. Renamed sewayaku (caretaker) the next year, abolished in Nov. 1904 |

Initially, dispatch and placement of coal diggers, later management of miners in company housing |

|

|

Apr. 1902 |

Kofukata torishimari (miner controller) placed under komu shunin (chief engineer) |

Miner control |

|

|

Feb. 1906 |

Kofu sewakata (miner caretakers) appointed |

|

|

|

Dec. 1913

|

Kofu shunin (miner chief) appointed |

Supervision of kofu gakari |

|

|

Feb. 1933 |

Kofu shunin changed to romu shunin, kofu gakari to romu gakari |

|

|

|

Aug. 1937 |

Romu ka (labor section) set up |

|

Note: These are examples of the company’s main operations at the time, but the other operations too went through much the same process with slight differences in scale and timing.

There was no noteworthy labor management aside from the above during the period from Mitsui’s establishment through to around 1920. However, it should be added that Mitsui too adopted a policy of elitism when it came to hiring miners, maintaining from the start a firm policy of not hiring anyone with an education beyond junior high graduation (Table 2), and in particular looking to ensure safety by recruiting through personal relationships. However, these were not policies limited to Mitsui, but were rather hiring policies maintained by most coal mines through to the outbreak of the Pacific War (Sekitan Kogyo Renmei, ed., Sekitan rodo nenkan 22 nendo ban [Coal mine labor almanac 1947], 68). In any case, thanks to this hiring policy and other factors, Mitsui experienced almost nothing that could be described as a labor dispute through to around 1918-19 (although Miike experienced frequent riots by prison labor).

The only other points worth special mention were perhaps the prison labor at Miike and the Yoron Islanders, as both groups required special labor management methods.

Prison labor was used at Miike from the period when the mine was under government management through to 1930. It was widely believed that Mitsui kept using prisoners as part of its low wage policy, with the practice attracting strident social criticism. In fact, however, with the exception of limited merits such as no need for recruiting and convenience in terms of training skilled miners, while wages might have been cheap, prison labor had many demerits: the prisoners were generally inefficient, for example, and it cost a lot for guard escorts and facilities to prevent prisoners escaping, etc. As a result, the prisoners ended up costing more than ryomin kofu, or law-abiding miners (as ordinary miners were called at Miike at the time); there was no labor force flexibility; work orders were not carried out quickly and accurately; and there was a lot of social criticism. Consequently, when the Manda pit was opened in 1902, despite the Miike prison asking the company to use prison labor in the pit, the company decided against it. Following the company’s purchase of the Miike mine, therefore, as the company became accustomed to recruiting miners, it gradually reduced the amount of prison labor, and in 1908 there were only 138 prisoners employed as coal diggers, a mere seven percent of the total number of coal diggers hired.

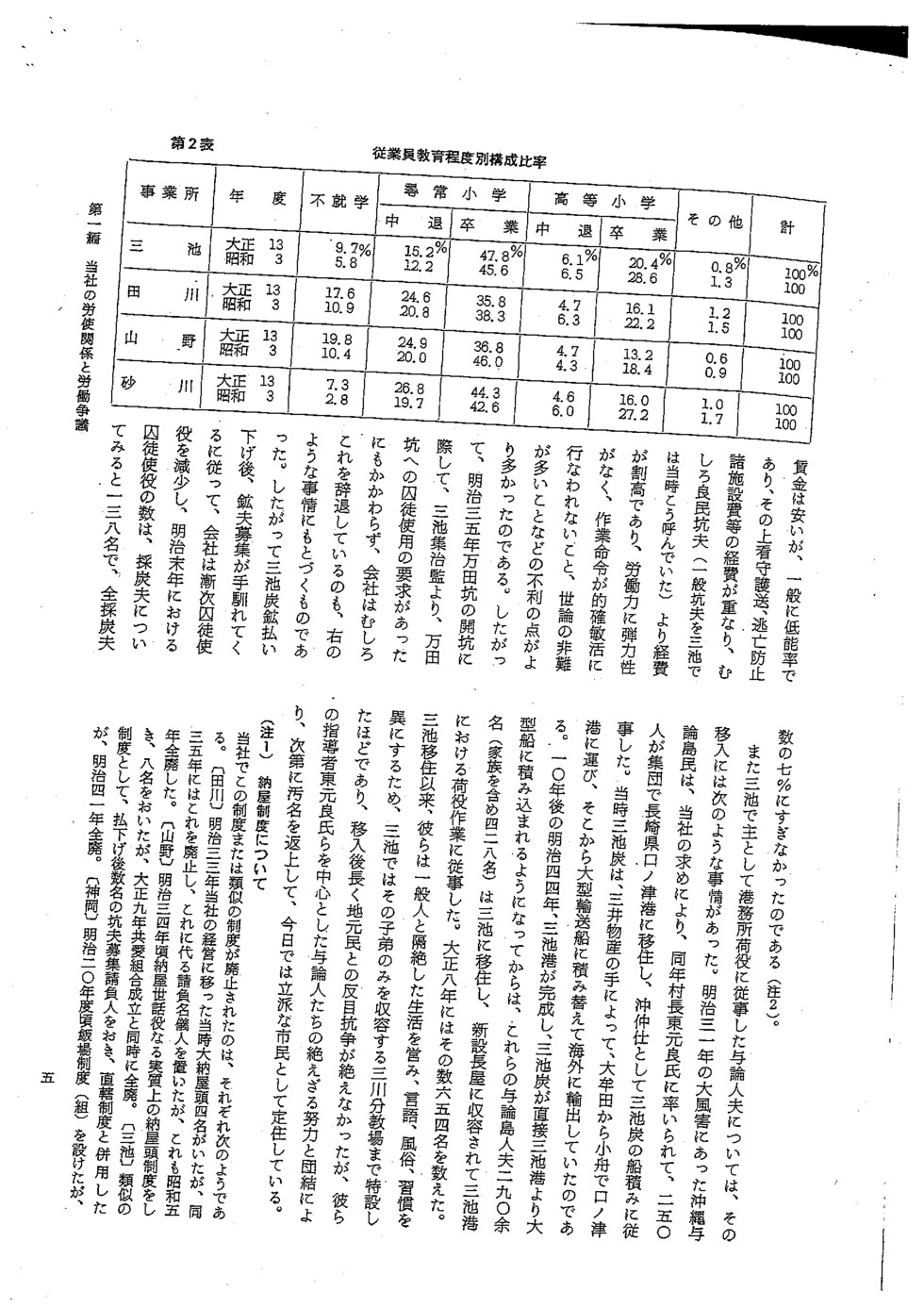

Table 2: Percentage of workers by level of education

|

Operation |

Year |

Unschooled |

Ordinary elementary school |

Higher elementary school |

Other |

Total |

||

|

Drop-outs |

Graduates |

Drop-outs |

Graduates |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Miike |

1924 |

9.7% |

15.2% |

47.8% |

6.1% |

20.4% |

0.8% |

100% |

|

1928 |

5.8% |

12.2% |

45.6% |

6.5% |

28.6% |

1.3% |

100% |

|

|

Tagawa |

1924 |

17.6% |

24.6% |

35.8% |

4.7% |

16.1% |

1.2% |

100% |

|

1928 |

10.9% |

20.8% |

38.3% |

6.3% |

22.2% |

1.5% |

100% |

|

|

Yamano |

1924 |

19.8% |

24.9% |

36.8% |

4.7% |

13.2% |

0.6% |

100% |

|

1928 |

10.4% |

20.0% |

46.0% |

4.3% |

18.4% |

0.9% |

100% |

|

|

Sunagawa |

1924 |

7.3% |

26.8% |

44.3% |

4.6% |

16.0% |

1.0% |

100% |

|

1928 |

2.8% |

19.7% |

42.6% |

6.0% |

27.2% |

1.7% |

100% |

|

Turning to the Yoron Islanders who served mainly as longshoremen for Miike’s port office, the circumstances behind their introduction were as follows. Following typhoon damage in 1898, 250 islanders led by village chief Motoyoshi Higashi responded to Mitsui’s request and came as a group to Kuchinotsu Port in Nagasaki Prefecture where they worked as stevedores, loading Miike coal on to ships. At the time, Mitsui Bussan carried Miike coal on small ships from Omuta to Kuchinotsu Port, where the coal was then loaded on to large freighters and exported overseas. Ten years later in 1911, Miike Port was completed and Miike coal could be loaded directly on to large ships from the port, at which time more than 290 Yoron Islanders (428 including their family members) shifted to Miike, where they were placed in new terrace housing and put to work loading ships at Miike Port. In 1919, that number had swelled to 654. After moving to Miike, the islanders lived completely separate from ordinary people, to the extent that, because of their different language, customs, and practices, a special classroom was even built at Mikawa solely for their children. For many years after shifting to Miike, they were constantly at odds with the locals, but thanks to their persistent efforts and solidarity, spearheaded by Motoyoshi Higashi and other leaders, they gradually improved their bad name and these days are permanently settled as upright citizens.

- Factory councils and industrial patriotic units (from around 1920 through to the end of the war)

After the end of World War I, Japan too was caught up in the wave of economic depression that swept the world, and in 1918, with social unease growing and rice riots breaking out nationwide, the above-mentioned riot also broke out at Miike’s Manda pit. After that incident, the focus of the company’s labor management shifted to preventing disputes, and Mitsui began to pay attention also to improving facilities and to educating and guiding workers, with labor management institutions too undergoing a radical overhaul by 1923-24. The kyoai kumiai (factory councils) which had been formed under the guidance of the company at all its operations in 1920 too were designed to back the company’s labor management, but attracted considerable outside attention as what was for the time a very progressive labor management formula. For the approximately 20 years from 1920 to 1940 when they were absorbed into the sangyo hokoku kai (industrial patriotic units), Mitsui’s labor management was primarily mediated through these factory councils.

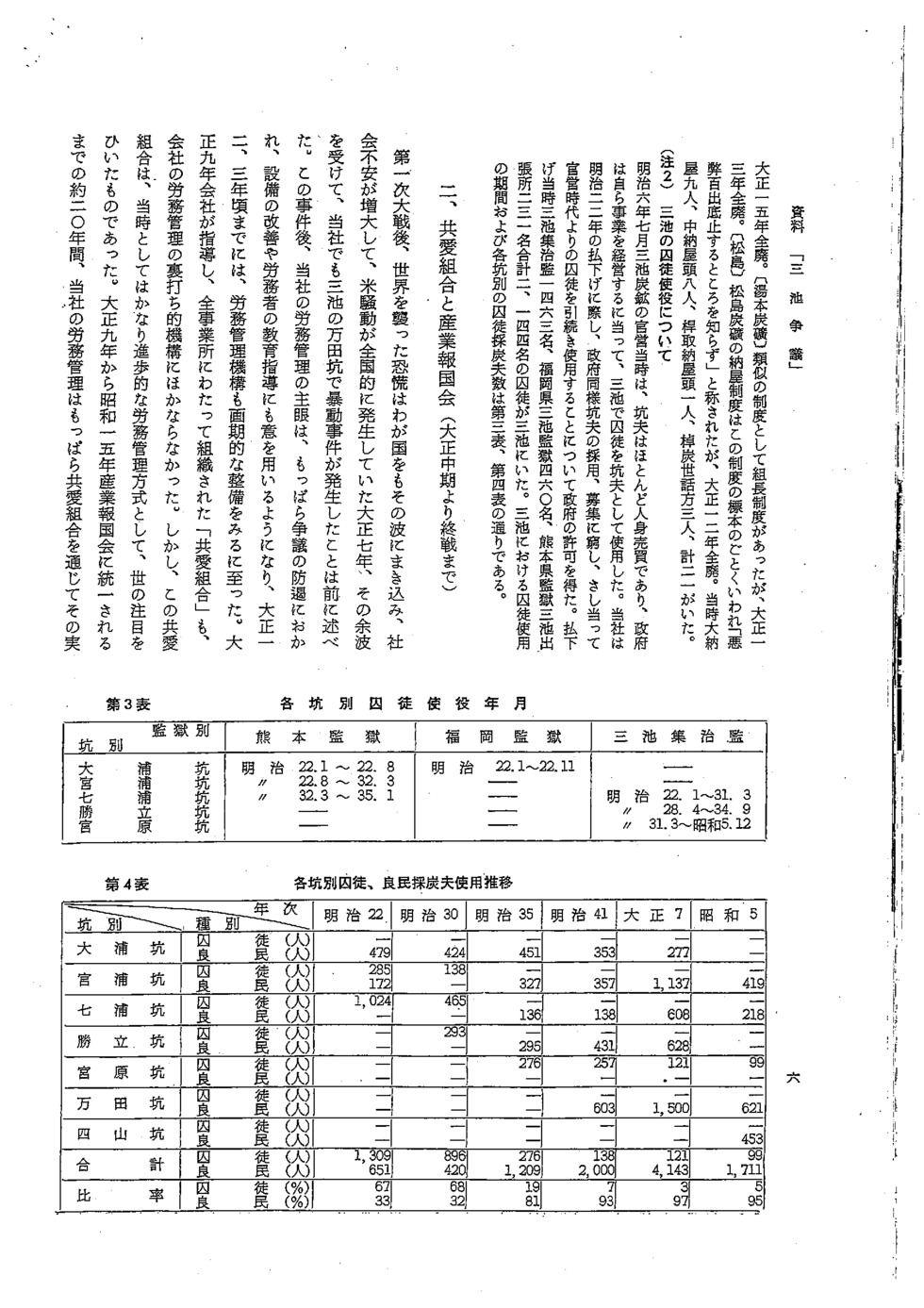

Table 3: Periods of use of prison labor by pit

|

|

By prison |

Kumamoto prison |

Fukuoka prison |

Miike prison |

|

By pit |

|

|||

|

Oura Pit |

Jan.-Aug. 1889 |

Jan.-Nov. 1889 |

|

|

|

Miyaura Pit |

Aug. 1889-Mar. 1899 |

|

|

|

|

Nanaura Pit |

Mar. 1899-Jan. 1902 |

|

Jan. 1889-Mar. 1898 |

|

|

Katsudachi Pit |

|

|

Apr. 1895-Sep. 1901 |

|

|

Miyanohara Pit |

|

|

Mar. 1898-Dec. 1930 |

|

Table 4: Use of prisoners and law-abiding citizens as coal diggers by pit

|

Year |

1889 |

1897 |

1902 |

1908 |

1918 |

1930 |

|

|

By pit |

By type |

||||||

|

Oura Pit |

Prisoners |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Law-abiding citizens |

479 |

424 |

451 |

353 |

277 |

- |

|

|

Miyaura Pit |

Prisoners |

285 |

138 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Law-abiding citizens |

172 |

- |

327 |

357 |

1,137 |

419 |

|

|

Nanaura Pit |

Prisoners |

1,024 |

465 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Law-abiding citizens |

- |

- |

136 |

138 |

608 |

218 |

|

|

Katsudachi Pit |

Prisoners |

- |

293 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Law-abiding citizens |

- |

- |

295 |

431 |

628 |

- |

|

|

Miyanohara Pit |

Prisoners |

- |

- |

276 |

257 |

121 |

99 |

|

Law-abiding citizens |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Manda Pit |

Prisoners |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Law-abiding citizens |

- |

- |

- |

603 |

1,500 |

621 |

|

|

Yotsuyama Pit |

Prisoners |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Law-abiding citizens |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

453 |

|

|

Total |

Prisoners |

1,309 |

896 |

276 |

138 |

121 |

99 |

|

Law-abiding citizens |

651 |

420 |

1,209 |

2,000 |

4,143 |

1,711 |

|

|

Ratio |

Prisoners |

67 |

68 |

19 |

7 |

3 |

5 |

|

Law-abiding citizens |

33 |

32 |

81 |

93 |

97 |

95 |

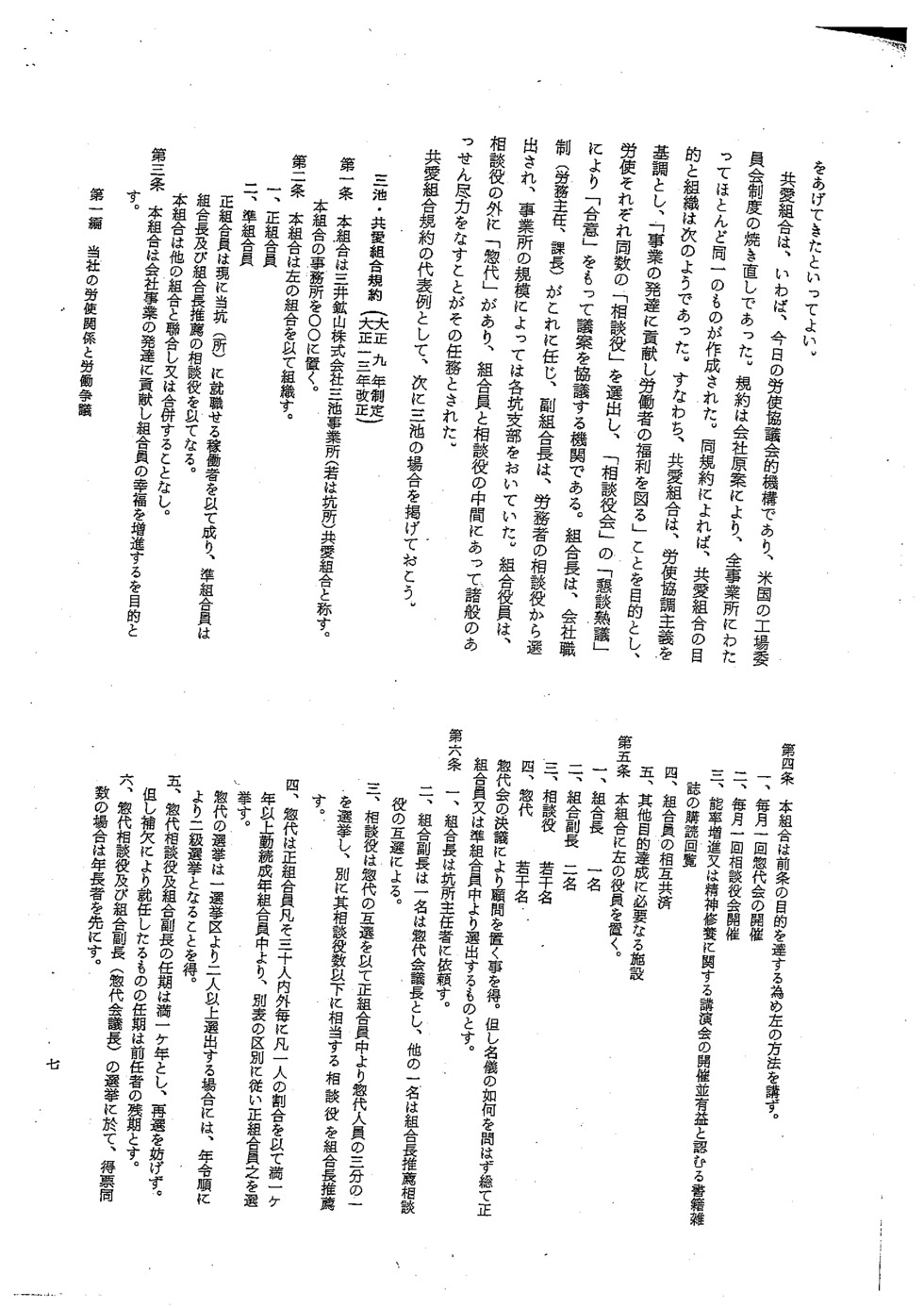

The factory councils were similar to today’s roshi kyogikai (labor-management consultative councils), and were an adaptation of the American shop committee system. The rules, drafted by the company, were virtually the same across all company operations. According to those rules, the purpose and organization of the councils were as follows. Based on the principle of labor-management consultation, the objective of the factory councils was to “contribute to the advance of business and promote the welfare of workers,” with an equal number of councilors representing labor and management selected to form a board of councilors which engaged in careful deliberations on agenda items in order to reach agreement. Each factory council was headed by a management-level company official (the labor chief or manager), while the vice-presidents were selected from among the councilors representing the workers’ side. At some large operations, a branch was set up for each pit. In addition to the councilors, representatives were also appointed whose job was to mediate between factory council members and the board of councilors.

The rules for the Miike factory council are noted as follows as a typical example.

Miike Factory Council Rules

(Formulated 1920)

(Revised 1924)

Article 1

This Factory Council shall be called the Mitsui Mining Company Miike Office (or Pit) Factory Council. The office of the Factory Council shall be located at XXX.

Article 2

The Factory Council shall comprise the following members:

(1) Full members

(2) Quasi-members

Full members shall comprise workers employed at the pit (office), while quasi-members shall comprise the Factory Council president and councilors recommended by the Factory Council president.

The Factory Council shall not ally or merge with another Factory Council.

Article 3

The purpose of the Factory Council shall be to contribute to the advance of company business and promote the welfare of Factory Council members.

Article 4

To achieve the above purpose, the Factory Council shall adopt the following methods:

(1) Hold a representatives meeting once monthly

(2) Hold a board of councilors meeting once monthly

(3) Hold lectures on improving efficiency and mental discipline and purchase and circulate books and magazines regarded as useful reading

(4) Provide mutual relief among Factory Council members

(5) Provide other facilities necessary to achieve the above purpose

Article 5

The following executives shall be appointed to the Factory Council:

(1) Factory Council president (1)

(2) Factory Council vice-presidents (2)

(3) Councilors (several)

(4) Representatives (several)

Advisors may be appointed at the decision of representatives. These must all be chosen from among full members or quasi-members, regardless of their title.

Article 6

(1) The pit head shall be asked to serve as the Factory Council president.

(2) One of the vice-presidents shall be the chair of the representatives meeting, and the other elected from among the councilors recommended by the president.

(3) Councilors shall comprise one third of representatives elected from among full members, along with a fewer number of councilors recommended by the president.

(4) One representative shall be chosen for every about 30 full members. Representatives shall be elected by full members in line with the categories in the appendix from among adult members who have a work record of at least one full year.

Where two or more people are selected for one electorate in the representative elections, a secondary election may be held in order of age.

(5) The term for representatives, councilors, and vice-presidents shall be one year, but they may be re-elected. However, a person selected to fill a vacancy shall serve for the remaining term of the predecessor.

(6) In elections of representatives, councilors, and vice-presidents (chair of the representatives meeting), where candidates win the same number of votes, the elder person shall be given the position.

Article 7

The Factory Council president shall represent the Factory Council and oversee all administration as well as convening and presiding over board of councilors meetings.

Where necessary, the Factory Council president may convene extraordinary board of councilors meetings and request the convention of extraordinary representatives meetings.

When the Factory Council president is absent, an acting president shall be recommended from among the vice-presidents.

Article 8

Councilors shall work to facilitate communication between Factory Council members and between the company and Factory Council members in the spirit of harmonious cooperation, and in the case of matters arising that obstruct this, may take the appropriate measures as unanimously agreed at a board of councilors meeting by those councilors in attendance.

Article 9

Representatives shall mediate between the Factory Council members from their electorates and the councilors who are elected by them.

Article 10

A representatives meeting shall be formed.

The chair of the representatives meeting shall be elected at the representatives meeting from among councilors who are full Factory Council members.

The chair of the representatives meeting shall convene and preside over said meeting.

When the chair of the representatives meeting is absent, an acting chair shall be recommended from among councilors who are full Factory Council members.

Article 11

In order for the representatives meeting to protect and promote Factory Council members’ common interests, they shall study and deliberate the following matters and present their resolutions to the board of councilors meeting.

(1) Matters relating to the promotion of Factory Council members’ welfare and efficiency

(2) Matters relating to operations or to oversight

(3) Matters relating to discipline, hygiene, and disaster prevention

(4) Matters relating to children’s education and the mental training of each individual

(5) Matters relating to mutual relief among Factory Council members

The representatives meeting shall hear the councilors’ report on agenda items from the board of councilors meeting and ask questions.

Article 12

The councilors shall form a board of councilors meeting.

Based on mutual understanding and trust between the company and Factory Council members, the board of councilors meeting shall deliberate carefully and reach agreement on agenda items put forward by the representatives meeting or by the company, and deal with these proposals accordingly.

The change of the Factory Council Rules, formulation, revision, or abolition of an agreement, disposition of Factory Council assets, or other critical matters shall be determined pursuant to a representatives meeting resolution and agreement from all councilors in attendance at a board of councilors meeting.

Agenda items at board of councilors meetings shall be reported to representatives meetings.

The Factory Council president may permit observers to attend the board of councilors meeting where the agenda allows. However, these observers must be full Factory Council members and must be fewer than the number of those councilors who are also full members.

In order to conduct the work of the Factory Council, the president may, with the agreement of the councilors, appoint a sewayaku (caretaker) or a dedicated secretary.

Article 13

The Factory Council shall formulate agreements in relation to relief matters for the purposes of mutual relief among full members, attending to the welfare of fellow members and gifting the following monies:

(1) A solatium in the case that a member is sick or injured

(2) Condolence money in the case of a member passing away

(3) Gift money in the case of a member enlisting, transferring, or retiring

(4) Gift money or a solatium in the case of a member getting married, having a child, or meeting with an accident

(5) Other necessary gift money

Article 14

Factory Council costs shall be covered by membership fees and subsidies from the company.

The monthly premium for full members shall be 30 sen for men and 15 sen for women and youths (under 16 years of age), to be taken out of their wages. The premium may be increased or decreased according to the financial circumstances of the Factory Council.

The company shall subsidize the Factory Council for an amount equivalent to full members’ fees.

Article 15

Persons wishing to leave the Factory Council will not have their fees refunded.

Article 16

The Factory Council president shall be responsible for safekeeping and investing Factory Council funds.

Article 17

Spending by the Factory Council shall be in accordance with the Factory Council Rules or various types of agreements. Extraordinary spending shall require the agreement of all members of the board of councilors meeting. In urgent cases, however, the approval of the board of councilors meeting can be sought after the fact.

Article 18

The president shall draw up a budget and financial statement for every term for the approval of the board of councilors meeting, whereupon this shall be reported to the representatives meeting.

Article 19

The Factory Council’s financial year shall start on XX day of XX month and finish on XX day of XX month.

Supplementary Provisions

Article 20

In the case that pre-existing agreements conflict with the Factory Council Rules, the Factory Council Rules shall prevail.

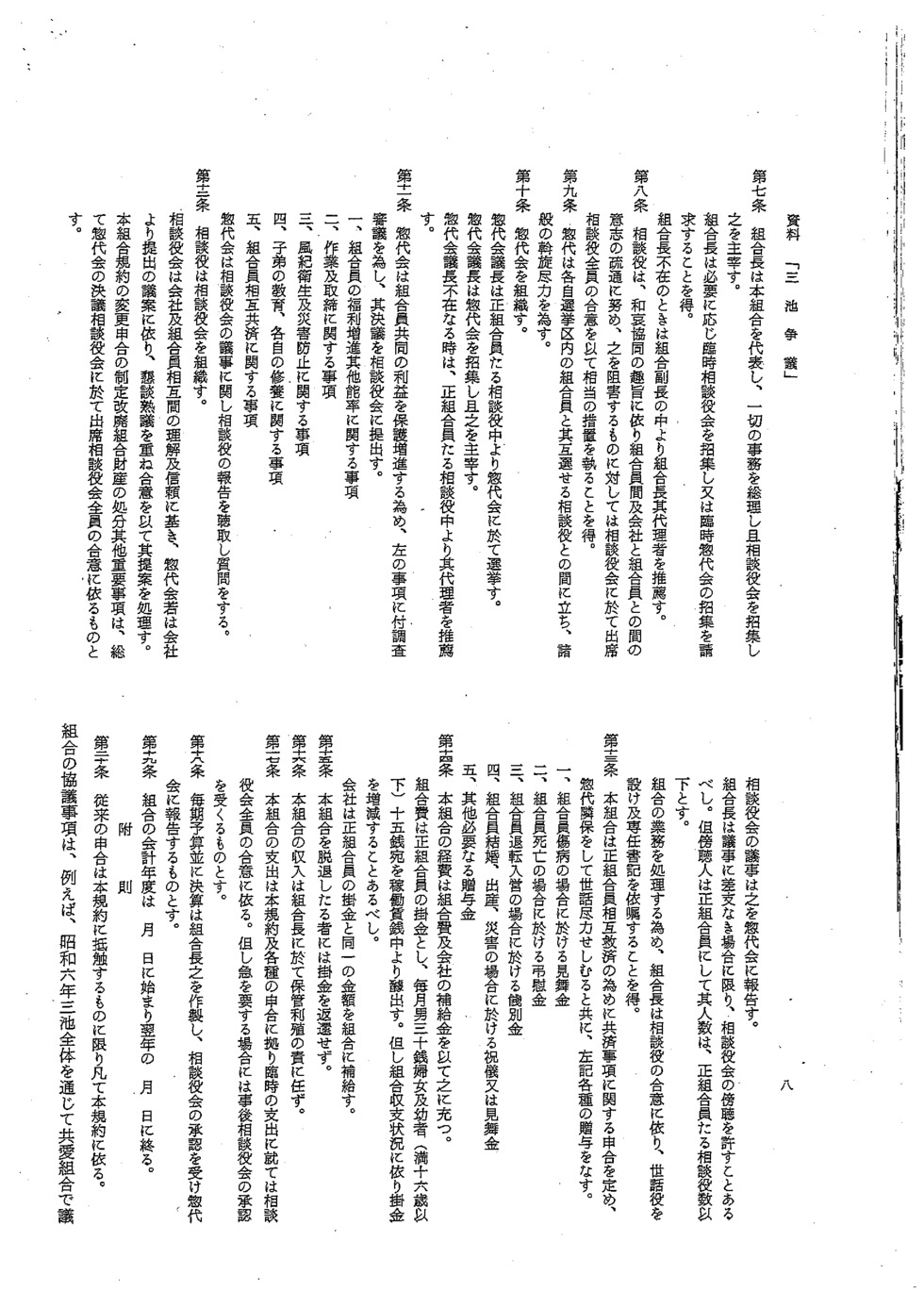

As to what was deliberated by factory councils, Table 5, for example, shows agenda items for Miike as a whole in 1931. As seen in the table, most of the matters raised at factory councils related to labor conditions.

Factory council activities covered all the company’s welfare-related initiatives such as mutual aid, the operation of purchasing groups or purchasing cooperatives (goods sales—directly operated by the company from 1889 to 1922; called baikanba or baibutten), financial cooperatives, savings facilities, and side work cooperatives, and the management and operation of physical education, relaxation, and entertainment facilities, with factory councils achieving some noteworthy results.

Table 5: Items discussed by factory councils (in the case of Miike in 1931)

|

Outcome |

Adopted |

Rejected |

Pending |

Withdrawn |

Total |

% |

|

Item |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wages, bonuses, benefits, etc. |

16 |

22 |

5 |

- |

43 |

5.5 |

|

Work facility-related |

221 |

28 |

22 |

2 |

273 |

35.6 |

|

Welfare facility-related |

115 |

14 |

25 |

5 |

159 |

20.7 |

|

Clinic and health-related |

25 |

6 |

4 |

- |

35 |

4.5 |

|

Purchasing cooperative-related |

36 |

11 |

27 |

4 |

78 |

10.2 |

|

Other matters |

54 |

26 |

12 |

6 |

98 |

12.7 |

|

Factory council operation-related |

59 |

10 |

11 |

- |

80 |

10.8 |

|

Total |

526 |

117 |

106 |

17 |

766 |

100 |

|

% |

68.7 |

15.3 |

13.8 |

2.2 |

100 |

|

None of the factory councils functioned very well in the early days, and in the case of Miike, the disputes at all Miike operations in 1924 (see Section 2) initially prompted action to close the factory council down. Subsequently, however, efforts were made to improve the factory council system and they began to function more smoothly, with the result that the company experienced no labor disputes through to the end of the war.

However, with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the government called for industrial peace in order to strengthen the wartime economy, and in late 1938, the government and the private sector together began promoting labor-management cooperation in the name of the Industrial Patriotic Movement. A succession of “industrial patriotic units” were subsequently formed in factories and offices around the country, and in April 1939, the government threw all its weight behind the Industrial Patriotic Movement as a national policy. A joint government-private sector industrial patriotic federation was set up in each prefecture, followed in November 1940 by the formation of the Great Japan Industrial Patriotic Association as the national control agency.

Mitsui too participated in this movement from an early point, transforming the existing factory councils into “Industrial (Mining) Patriotic XX Mine Councils.” Moreover, in 1941, following the formation of the Great Japan Industrial Patriotic Association, at the advice of the government authorities, these councils again underwent a major transformation pursuant to the Great Japan Industrial Patriotic Association’s guidelines for development of industrial patriotic organizations, with the title “Factory Council” abolished and replaced with “Industrial Patriotic Unit.” This marked the complete disappearance of the factory councils and their 20-year history, with every single council standardized into the required Industrial Patriotic Unit. These units were organized into a hierarchy geared to the workplace but using exactly the same structure as the military, with the president (mine or plant manager) as the commander in chief, each unit headed by a commander, and five-person crews created right at the bottom of the structure, ensuring a chain of command that reached to all corners of the workplace.

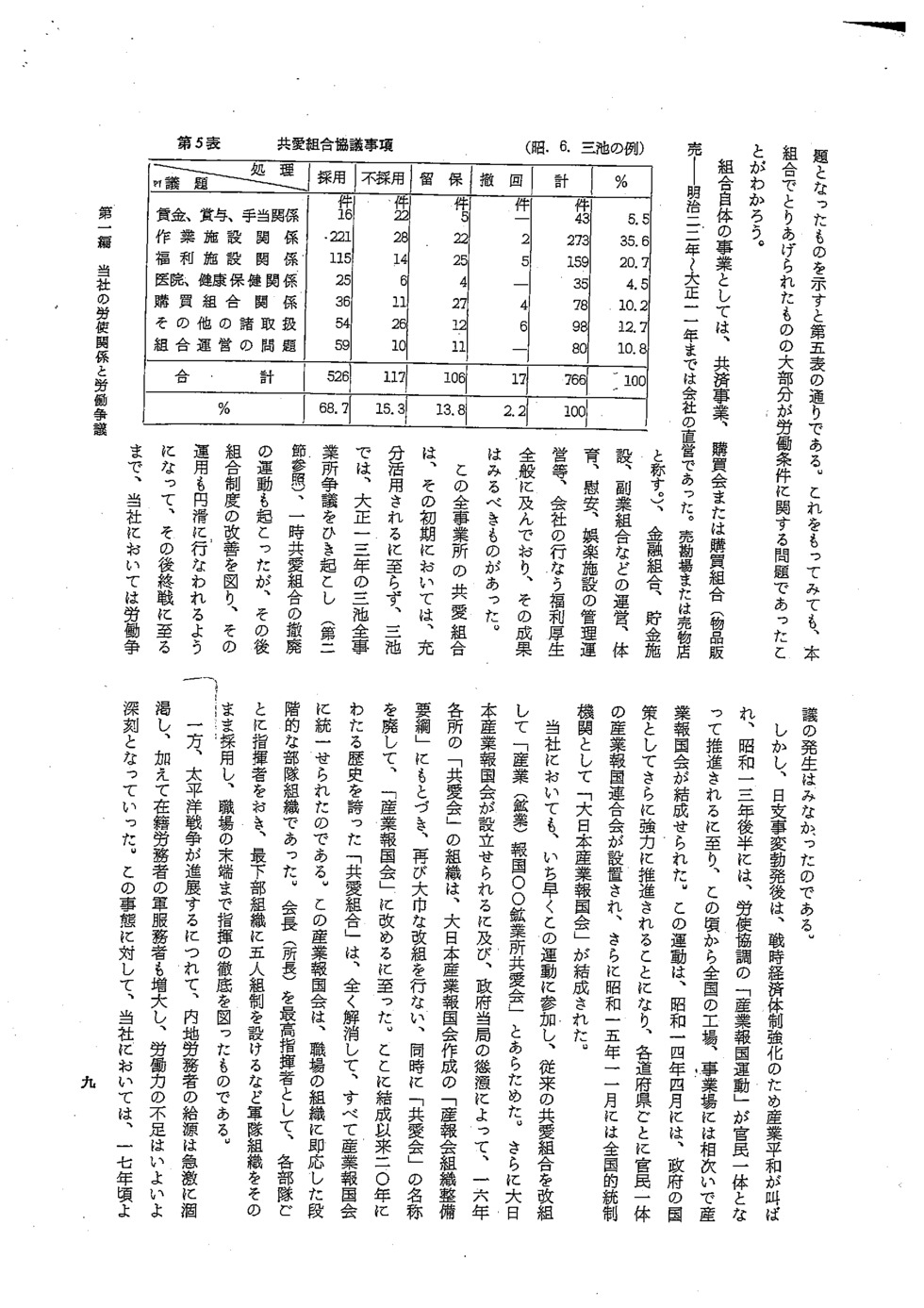

As the Pacific War unfolded, domestic labor sources dried up rapidly even as a growing number of registered laborers became military servicemen, with the consequence that the company found itself faced with a serious labor shortage. As of around 1942, to make up for the shortage of labor, Mitsui decided to focus on inputting Korean labor and to cover the remaining shortfall by using the labor service corps, Chinese workers, or white prisoners of war, working to maintain production somehow.

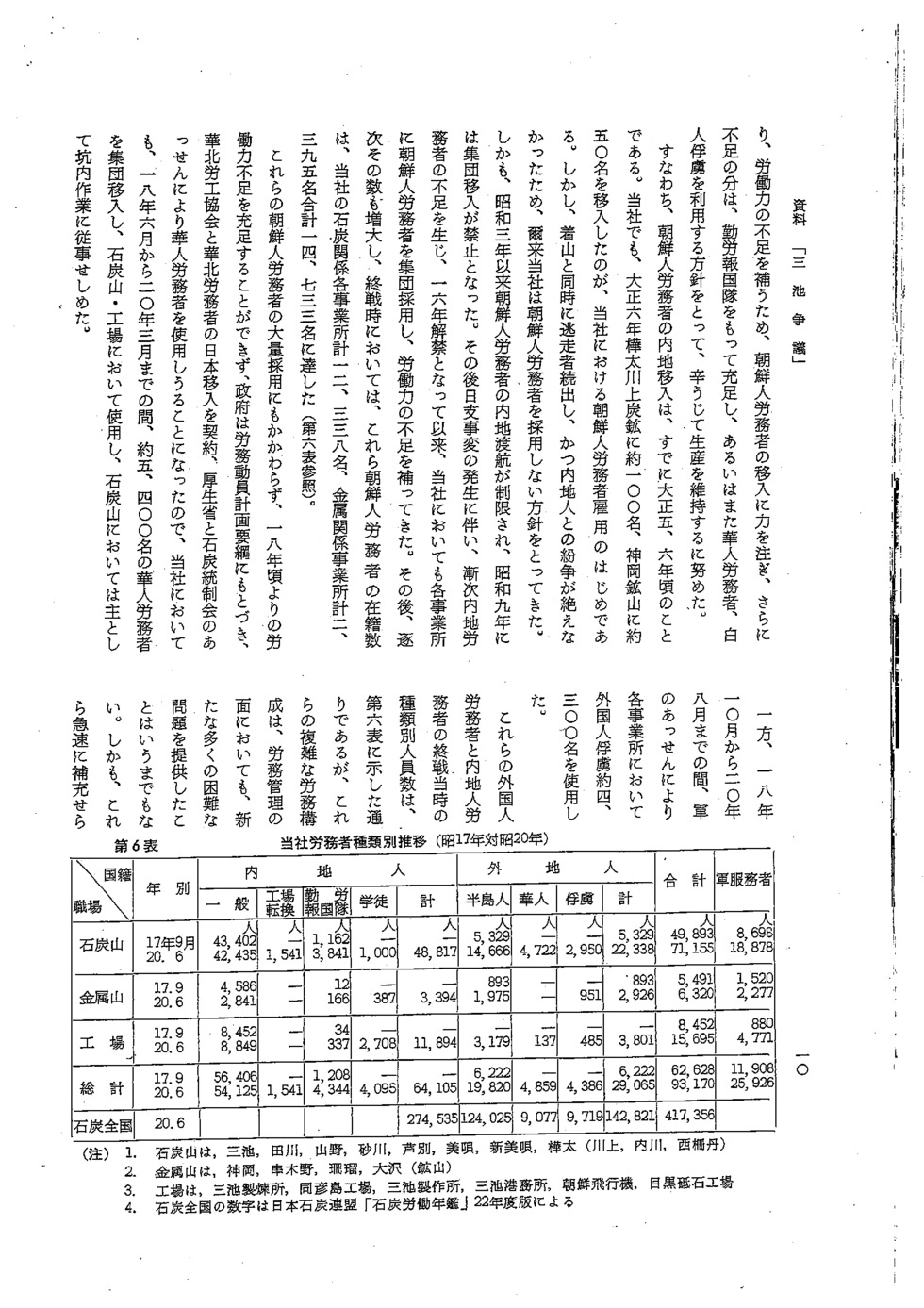

Japanese companies had in fact brought in Korean workers back in 1916-17. Mitsui began employing Koreans in 1917, with around 100 personnel going to the Kawakami mine in Sakhalin and around 50 to the Kamioka mine. But when a succession of Korean laborers ran away almost as soon as they arrived at the mine, and then there was endless trouble between these workers and the Japanese, Mitsui had decided not to take on any more Koreans. In addition, the government restricted Korean workers coming to Japan as of around 1928, going on to ban mass migration in 1934. Subsequently, following the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japan gradually began to suffer a shortage of local labor, and when the ban on Korean workers was lifted in 1941, Mitsui too began hiring groups of Korean workers and using them to cover the shortfall. The number subsequently gradually increased, and by the end of the war, Mitsui had 12,338 Korean workers at its coal-related operations and 2,395 at its metal-related operations, making a total of 14,733 (Table 6).

Despite the mass hiring of Korean workers, it was impossible to cover the labor shortage that arose as of around 1943, and the government drew up guidelines for a labor mobilization plan which opened the way for contracting the North China Industrial Labor Association to send North Chinese workers to Japan through the mediation of the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Coal Control Association. Mitsui consequently brought in around 5,400 Chinese workers in groups over the period from June 1943 to March 1945 to use in coal mines and factories, with those workers sent to coal mines employed primarily for underground work.

Table 6: Mitsui workers by type (1942 vs 1945)

|

Nationality

Workplace |

Year YearwYear

|

Japanese

|

Foreigners

|

Total

|

Military servicemen |

|||||||

|

General

|

From factories

|

Labor service corps |

Students

|

Total

|

Koreans

|

Chinese

|

Prisoners of war

|

Total

|

|

|

||

|

Coal mines

|

Sep. 1942 Jun. 1945 |

43,402 42,435 |

- 1,541 |

1,162 3,841 |

- 1,000 |

- 48,817 |

5,329 14,666 |

- 4,722 |

- 2,950 |

5,329 22,338 |

49,893 71,155 |

8,698 18,878 |

|

Metal mines

|

Sep. 1942 Jun. 1945 |

4,586 2,841 |

- -

|

12 166

|

- 387 |

- 3,394 |

893 1,975 |

- -

|

- 951 |

893 2,926 |

5,491 6,320 |

1,520 2,277 |

|

Factories

|

Sep. 1942 Jun. 1945 |

8,452 8,849 |

- - |

34 337 |

- 2,708 |

- 11,894 |

- 3,179 |

- 137 |

- 485 |

- 3,801 |

8,452 15,695 |

880 4,771 |

|

Total

|

Sep. 1942 Jun. 1945 |

56,406 54,125 |

- 1,541 |

1,208 4,344 |

- 4,095 |

- 64,108 |

6,222 19,820 |

- 4,859 |

- 4,386 |

6,222 29,065 |

62,628 93,170 |

11,908 25,926 |

|

Coal mines nationwide |

Jun. 1945

|

|

|

|

|

274,535 |

124,025 |

9,077 |

9,719 |

142,821 |

417,356 |

|

Notes:

- “Coal mines” denotes Miike, Tagawa, Yamano, Sunagawa, Ashibetsu, Bibai, Shin-Bibai, and Sakhalin (Kawakami, Naikawa, Nishisakutan).

- “Metal mines” denotes Kamioka, Kushikino, Sanru, and Osawa.

- “Factories” denotes Miike Seirensho, Miike Seirensho’s Hikoshima plant, Miike Seisakusho, Miike Komusho, Chosen Hikoki, and Meguro Toishi Kojo.

- The nationwide figures are from Nihon Sekitan Renmei, Sekitan rodo nenkan 22 nendo ban [Coal mine labor almanac 1947].

Through military mediation, from October 1943 to August 1945, Mitsui also used around 4,300 foreign prisoners of war in its various operations.

Table 6 shows the number of foreign and domestic workers by type at the end of the war. It hardly needs to be said that this complex labor composition presented many new, difficult labor management issues, while workers brought in so quickly to cover shortfalls also included many low-quality personnel with limited efficiency. The workers sent over from China from the end of 1944 through 1945 in particular included many who were unsuited for mine labor, opium-addicted, physically infirm, or malnourished, because the North China Industrial Labor Association was simply looking at numbers, rather than considering the physical suitability for mine work of the individuals they sent.

As a result, while supplementing the mine labor force from these various sources might have secured the required number of workers, production plummeted just at the time when the war was coming to an end.

Section 2: Major labor disputes in the prewar period

From the time that the company was established through to the end of the war, the only labor disputes at mines or factories directly operated by Mitsui occurred at Miike and Hikoshima (a smelter). Kamioka and Yumoto both experienced very minor disputes, and there were no other incidents elsewhere bearing mention. At affiliate companies too, the only dispute was at the Matsushima coal mine.

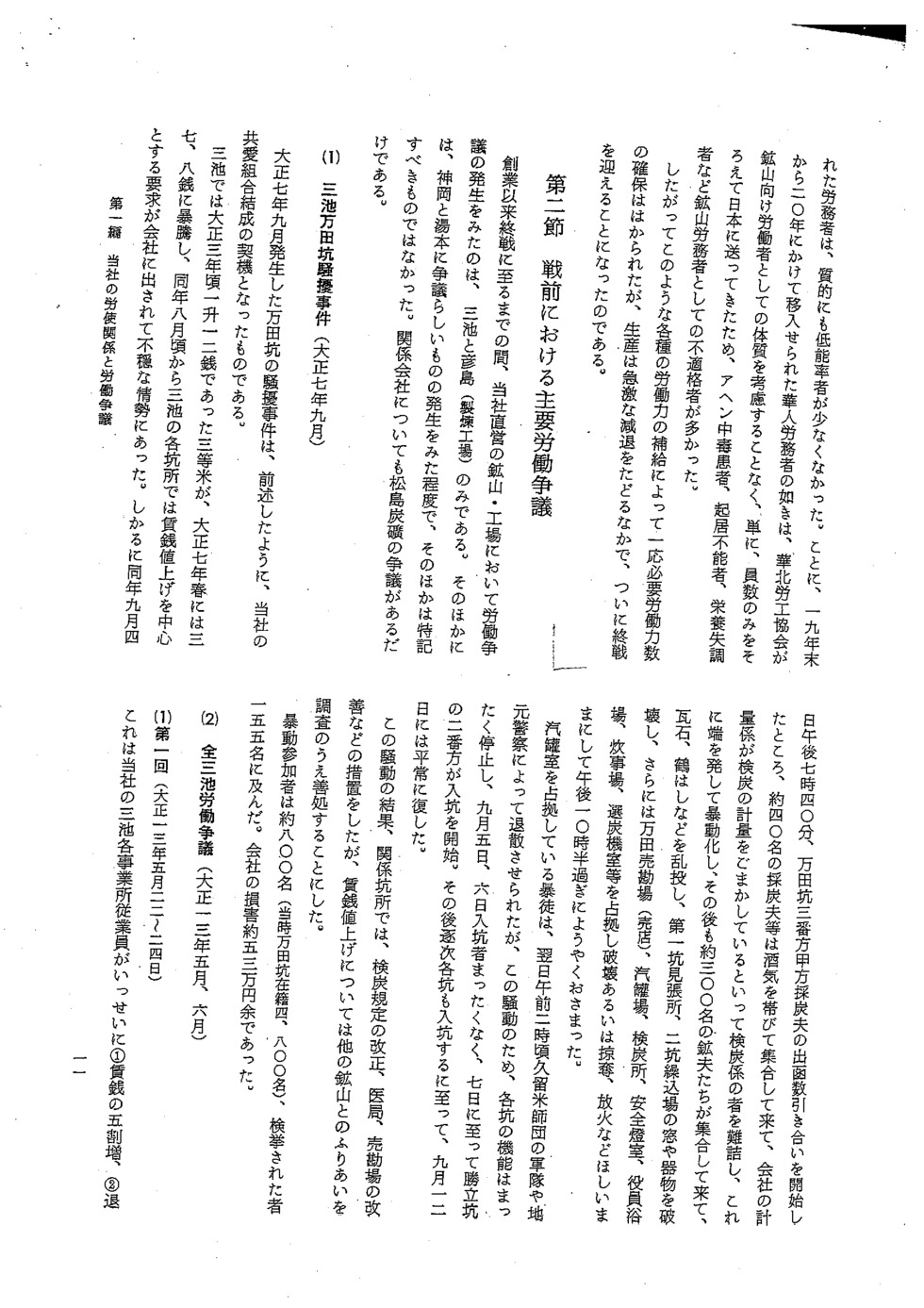

(1) Riot at Miike’s Manda pit (September 1918)

As noted above, the Manda pit riot which occurred in September 1918 became the motivation for setting up Mitsui’s factory councils.

At Miike, where third-class rice had cost 12 sen per sho (a traditional measurement equivalent to approximately 1.8 liters) in 1914, the spring of 1918 saw this price soar to 37 or 38 sen, and as of around August, Miike’s various pits began to receive demands primarily that the company raise wages, giving rise to an ugly atmosphere. On September 4, 1918 at 7:40 in the evening, when apportionment of the output of Manda Pit Third-Shift A coal diggers began, a group of around 40 coal diggers and other individuals smelling of alcohol gathered, saying that the company’s measuring officer was fiddling with the coal measuring weights and taking to task the person in charge of checking the coal. This developed into violence, with around 300 miners subsequently gathering and hurling rubble, picks, etc., breaking windows and other property at the Shaft 1 lookout and the Shaft 2 transfer station, and occupying, destroying, or pillaging and setting fire to the Manda store, boiler room, coal inspection station, lamp house, senior staff bathroom, kitchen, coal washing room, etc. as they saw fit until around half past 10 that night.

The mob that occupied the boiler room was sent packing by the Kurume army division and local police at around two the next morning, but the riot closed down all the functions of each pit completely, and no one at all went into the mine on September 5 or 6. On the 7th, the Katsudachi Pit Second-Shift miners started going into the mine, and after that, the other pits gradually followed, with everything back to normal by September 12.

As a result of this riot, the various pits revised their coal inspection rules, improved medical clinics and stores, and carried out other measures, but in relation to raising wages, they opted to examine the relationship with other mines before taking appropriate steps.

Around 800 people took part in the riot (of the 4,800 employed at the Manda pit), and 155 were arrested. The damages to the company amounted to more than 530,000 yen.

(2) The Miike labor disputes (May and June, 1924)

(a) The first Miike labor dispute (May 22 to 24, 1924)

This was the first real labor dispute which the company had experienced, involving staff at all Miike operations going on strike on May 22 to 24, 1924 to demand (1) a 50 percent wage rise, (2) a bigger retirement benefit (from the equivalent of 10 days’ wages per annum to 30 days’ wages), and (3) abolition of the factory councils.

The main agents in the dispute were workers at Miike Seisakusho. Backed by the Miike Rodo Domei (an outside labor federation for Miike), local merchants disgruntled at factory council purchasing groups, and others, the incident developed into a dispute. Factory councils had not long been formed, and their poor operation led to a great deal of worker dissatisfaction. However, negotiations between strike representatives and the company resulted in the cessation of hostilities until the regular wage rise on June 1, and the strikers withdrew all their demands, with the dispute ending peacefully aside from the strike.

(b) The second Miike labor dispute (June 6 to July 7, 1924)

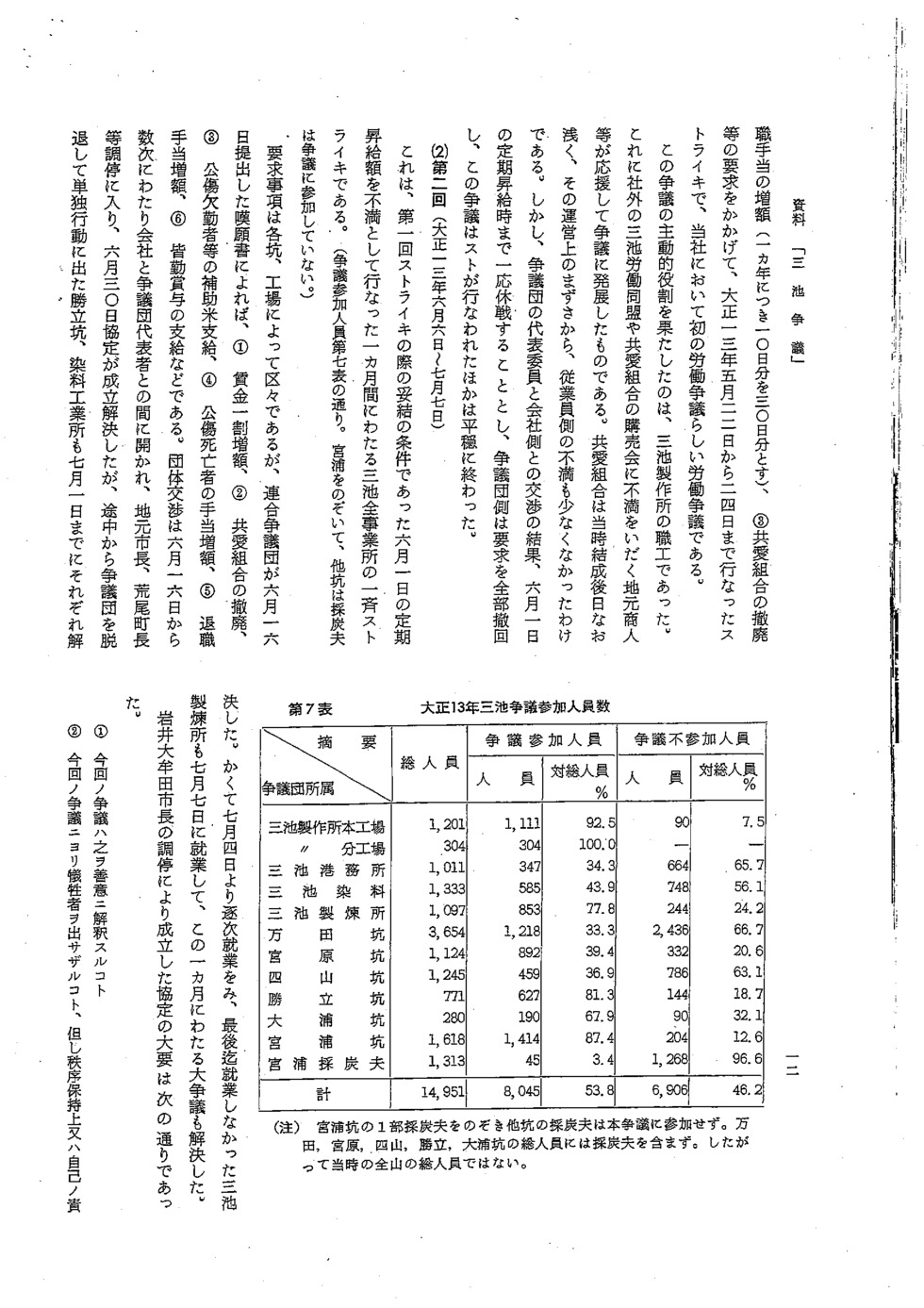

This was a month-long strike across all Miike operations arising out of dissatisfaction with the amount granted in the regular wage rise on June 1, which had been a condition for settling the first strike. (The participants in the dispute are noted in Table 7. With the exception of Miyaura, coal diggers from the other pits did not take part.)

While different pits and factories had different demands, the petition submitted by the strike confederation on June 16 contained the following: (1) a 10 percent wage rise; (2) abolition of factory councils; (3) an extra rice allocation for workers absent from work because of injuries sustained in the course of their duties; (4) an increase in the benefit for workers dying in the course of their duties; (5) an increase in the retirement benefit; and (6) payment of an attendance bonus. Collective bargaining was held several times from June 16 between the company and strike representatives. The local city mayor, the Arao mayor, and other figures became involved in mediation, and an agreement was concluded on June 30 which settled the dispute. The Katsudachi pit and Miike Senryo Kogyosho, which had split along the way from the strike confederation and taken their own course, reached separate settlements by July 1. As of July 4, workers gradually returned to their duties, with Miike Seirensho, which was the final place where workers returned to work, seeing its workers back in their posts on July 7. This major dispute too was consequentially settled in the space of a month.

Table 7: No. of participants in the 1924 Miike labor dispute

|

Confederation members |

Outline |

Total no. of people |

Strike participants |

Non-participants |

||

|

No. |

% of total |

No. |

% of total |

|||

|

Miike Seisakusho main factory |

1,201 |

1,111 |

92.5 |

90 |

7.5 |

|

|

Miike Seisakusho branch factory |

304 |

304 |

100.0 |

- |

- |

|

|

Miike Komusho |

1,011 |

347 |

34.3 |

664 |

65.7 |

|

|

Miike Senryo Kogyosho |

1,333 |

585 |

43.9 |

748 |

56.1 |

|

|

Miike Seirensho |

1,097 |

853 |

77.8 |

244 |

24.2 |

|

|

Manda Pit |

3,654 |

1,218 |

33.3 |

2,436 |

66.7 |

|

|

Miyanohara Pit |

1,124 |

892 |

39.4 |

332 |

20.6 |

|

|

Yotsuyama Pit |

1,245 |

459 |

36.9 |

786 |

63.1 |

|

|

Katsudachi Pit |

771 |

627 |

81.3 |

144 |

18.7 |

|

|

Oura Pit |

280 |

190 |

67.9 |

90 |

32.1 |

|

|

Miyaura Pit |

1,618 |

1,414 |

87.4 |

204 |

12.6 |

|

|

Miyaura coal diggers |

1,313 |

45 |

3.4 |

1,268 |

96.6 |

|

|

Total |

14,951 |

8,045 |

53.8 |

6,906 |

46.2 |

|

Note: With the exception of some coal diggers from the Miyaura pit, no coal diggers from the other pits participated in the dispute. The total number of people for the Manda, Miyanohara, Yotsuyama, Katsudachi, and Oura pits does not include coal diggers, so the total figure above does not represent the actual total number of people at all pits at the time.

The broad outlines of the agreement reached through the mediation of Omuta City Mayor Iwai were as follows.

(a) To take the current dispute in good part;

(b) To avoid the dispute producing any victims and to restore everything to its former state, even though some persons who are unable to maintain order or who are willing to accept personal responsibility may be removed in consultation with the mayor;

(c) To undertake a study of matters in good faith and to ensure that those elements requiring improvement are in fact improved, with the exclusion of anything relating to wages, seeking to increase income through other means such as improving efficiency;

(d) To work to improve factory councils as the institutions coordinating between the company and labor and to ensure their smooth utilization, as well as to find the best means of promoting communication with employees and ensuring goodwill; and

(e) For the company to institute some small relief methods for the strikers.

The total direct damages from the dispute were 550,000 yen for Miike Kogyosho and Miike Seisakusho, and the company subsequently phased in a number of reforms including: (1) amendment of the factory council rules (more representatives, establishment of a representatives meeting, establishment of a system for observers to attend a board of councilors meeting, etc.); (2) a special wage payment (25 sen per person); (3) establishment of a system for providing rice to people absent from work and a system for lending goods from the purchasing cooperative; (4) establishment of a special wage system for contract unit price changes; (5) amendment of the rules for rewarding coal diggers’ work attendance; and (6) improvement of the pension system. As a result, Mitsui became much more careful about labor management as well, with almost no labor disputes arising at the company subsequently through to the end of the war.

(3) Hikoshima Claude-method factory dispute (July 21 to August 3, 1931)

Of the 154 workers registered at the smelter attached to this factory, 112 presented a request for formal approval for joining a labor union (at the time, around 30 workers had set up and joined a labor union). On July 21, 1931, they set up a strike headquarters in front of the factory and held a strike for over 30 days, but this ultimately ended in the complete defeat of the strikers. During the strike, some members went into the factory and turned off switches, stopping all the machinery, and the strikers also engaged in demonstrations and propaganda with the support of fellow workers from other parts of Japan. However, when the company dismissed the 20-odd workers who had engaged in actions injurious to the company during the strike for reasons of misconduct, the strike group rapidly fell apart.

(4) Matsushima coal mine dispute (October 1926)

The Matsushima coal mine operated on a typical bunkhouse system which had caught the eye of official circles, and it was this system that was involved in the dispute which occurred.

The cause of the dispute was a combination of the bunkhouse foremen’s resentment of miner chiefs, their dissatisfaction with company policy, and miner dissatisfaction with the company. The trigger was a labor union called Kojokai set up on October 3, 1926 by more than 20 middle-level bunkhouse foremen and the 500 miners they controlled, which the company tried to prevent. Initially, the senior bunkhouse foremen sided with the company and sought to dissolve the union, but later they switched to the miners’ side. When the union presented demands for better treatment of the miners on October 11, the senior bunkhouse foremen worked with the middle-level bunkhouse foremen to force the company to respond to those demands. Fifteen demands were presented, including: (a) a wage rise; (b) an increase in the dismissal benefit; (c) payment of an allowance for continued service; and (d) construction or improvement of entertainment and hygiene facilities. The company had no choice but to accept all these demands, which it did on October 15, with the dispute ending that day.

This dispute also led to the total abolition of Matsushima’s infamous bunkhouse system in July 1929.

Chapter 1: Formation of labor unions and the launch of a federation of labor unions in the same corporate group

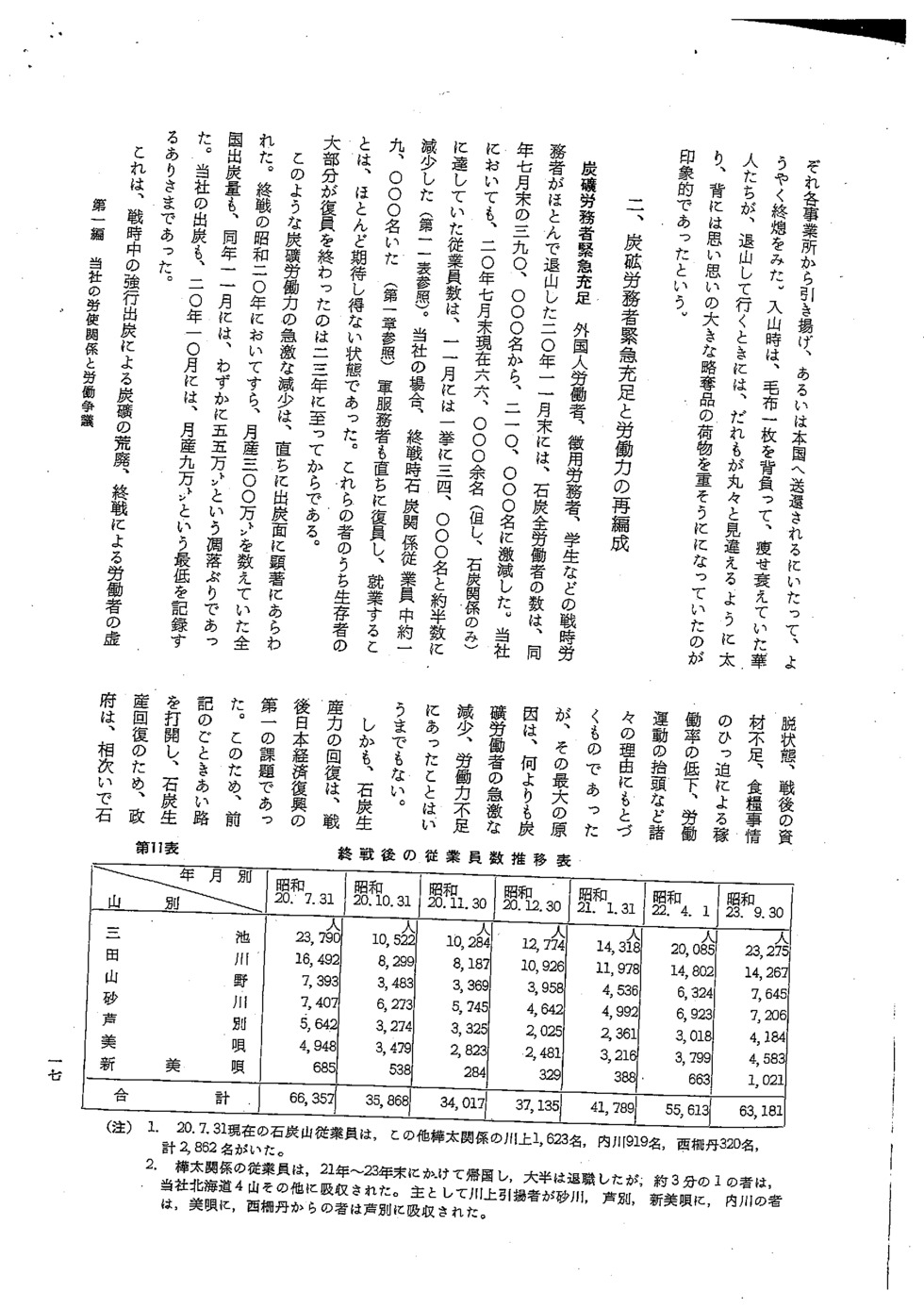

Section 1: Postwar reorganization of coal mine labor

- Trouble caused by Korean and Chinese workers

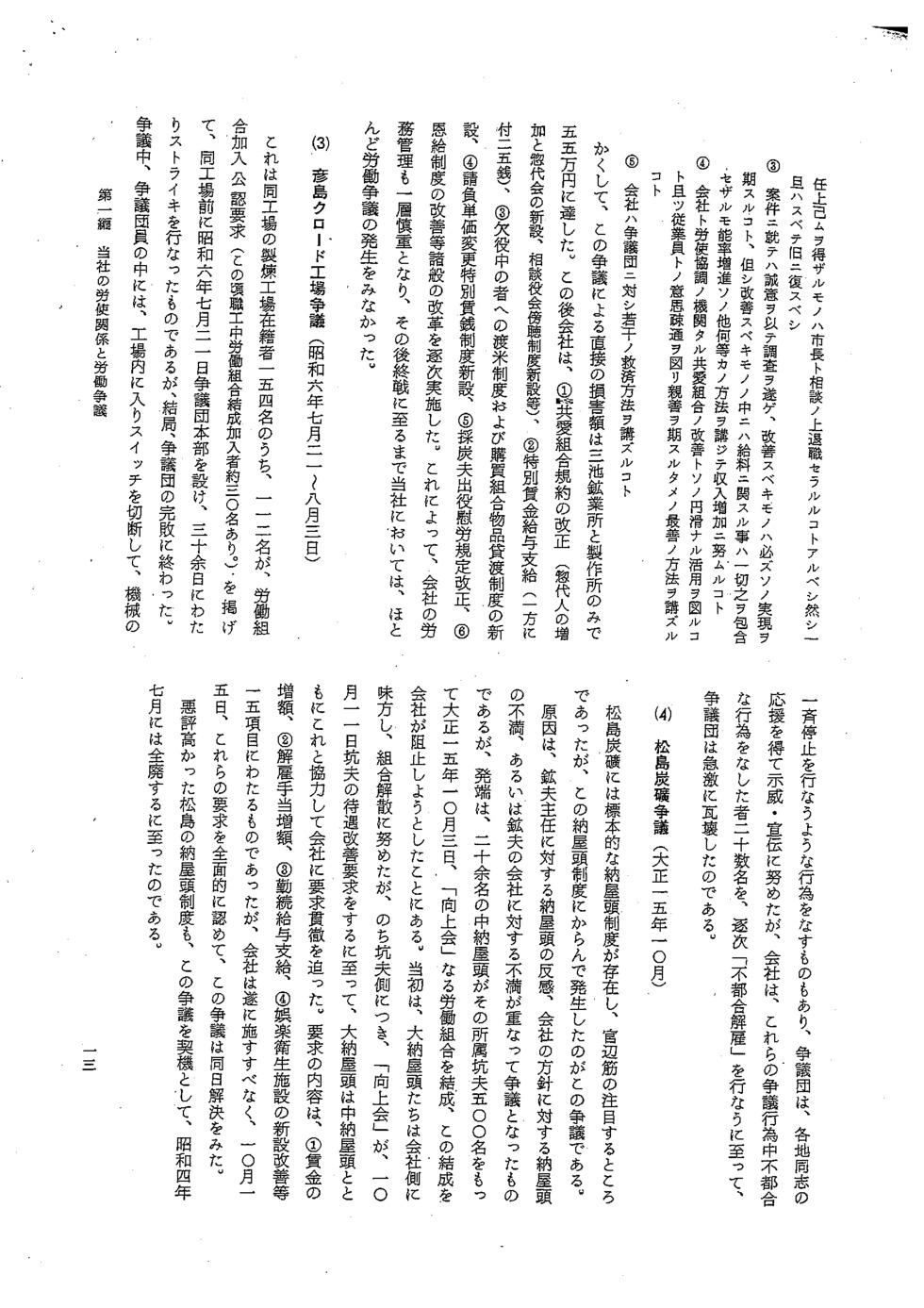

Immediately after the war ended in August 1945, the labor problem which the company faced was the trouble caused by Korean and Chinese workers, huge numbers of whom had been employed during the war. At the end of the war, the company was using a total of 12, 338 Korean workers in its seven coal-related operations and 2,395 in its seven metal-related operations, while the total number of Chinese workers at six of the company’s coal-related operations (excluding Shin-Bibai) was 4,811, and on the metal operations side, 99 at the Hibi smelter (Table 8). In terms of other foreigners, the company was using 3,421 prisoners of war for coal-related labor, 1,428 for metal-related labor, and 45 at Miike Komusho, but it was Chinese and Korean workers who after the end of the war began stealing goods, assaulting and threatening company executives and employees, and damaging property, among other actions, terrifying Japanese employees so badly that they began not showing up to work or quitting entirely so as to avoid trouble. The extremity of the disruption can be gleaned from Table 9, which presents a study on the damage caused by violence by Koreans and Chinese in coal mines at the end of the war, but here I shall give a few examples of Chinese violence, which was particularly extreme. The company argued that it was employing Chinese workers on a contract basis, but the Occupation Forces did not accept this and treated them as prisoners of war.

Table 8: No. of foreign workers by operation at the end of the war (as at Aug. 1945)

|

Outline |

Operation |

Koreans |

Chinese |

Prisoners |

|

Business type |

||||

|

Coal-related operations |

|

|

|

|

|

Miike |

2,297 |

2,348 |

1,409 |

|

|

Tagawa |

2,195 |

623 |

398 |

|

|

Yamano |

1,850 |

581 |

573 |

|

|

Sunagawa |

2,137 |

385 |

- |

|

|

Ashibetsu |

2,055 |

440 |

611 |

|

|

Bibai |

1,418 |

434 |

430 |

|

|

Shin-Bibai |

386 |

- |

- |

|

|

Coal mine total |

12,338 |

4,811 |

3,421 |

|

|

Metal-related operations |

Kamioka |

1,297 |

- |

945 |

|

Osawa |

48 |

- |

- |

|

|

Aso |

215 |

- |

- |

|

|

Miike Seirensho |

400 |

- |

283 |

|

|

Hikoshima |

236 |

- |

- |

|

|

Hibi |

99 |

99 |

200 |

|

|

Takehara |

100 |

- |

- |

|

|

Total for metal-related operations |

2,395 |

99 |

1,428 |

|

|

Other |

Miike Komusho |

- |

- |

45 |

|

Total |

|

14,733 |

4,900 |

4,894 |

The Chinese at Miike armed themselves with small arms and light machine guns after the war, and demanded that they be supplied with clothing, food, money, etc., within a stipulated time, or took personal sanctions against mine employees, against which the company was almost helpless. Some of the Chinese at the Manda, Yotsuyama, and Miyaura pits were from the National Revolutionary Army or the Eighth Route Army, and at the Manda and Yotsuyama pits, they shot at each other with machine guns, while the unit head at Yotsuyama was killed by someone from the Manda group. On September 17, 1945, an Allied Forces unit charged with evacuating prisoners of war disarmed the Chinese, and eventually this trouble died down.

At Sunagawa, there were frequent incidents of Chinese beating up employees, with a string of labor assistants leaving the mine out of fear of this. The Chinese also invaded employee housing, the company club, and other premises, threatening employees. At one stage, it really became a touch and go situation, but on October 19, the Chinese were sent back to China from Muroran, effectively putting an end to the problem.

At Bibai, there were frequent incidents such as imprisoning the mine manager, stealing clothing, watches, fountain pens, etc. (some people even wore several of the stolen watches on both arms), interruption of train operations, and violence against a Korean dormitory head, a police officer, and other people, and many labor assistants and coal diggers began leaving the mine because of the danger.

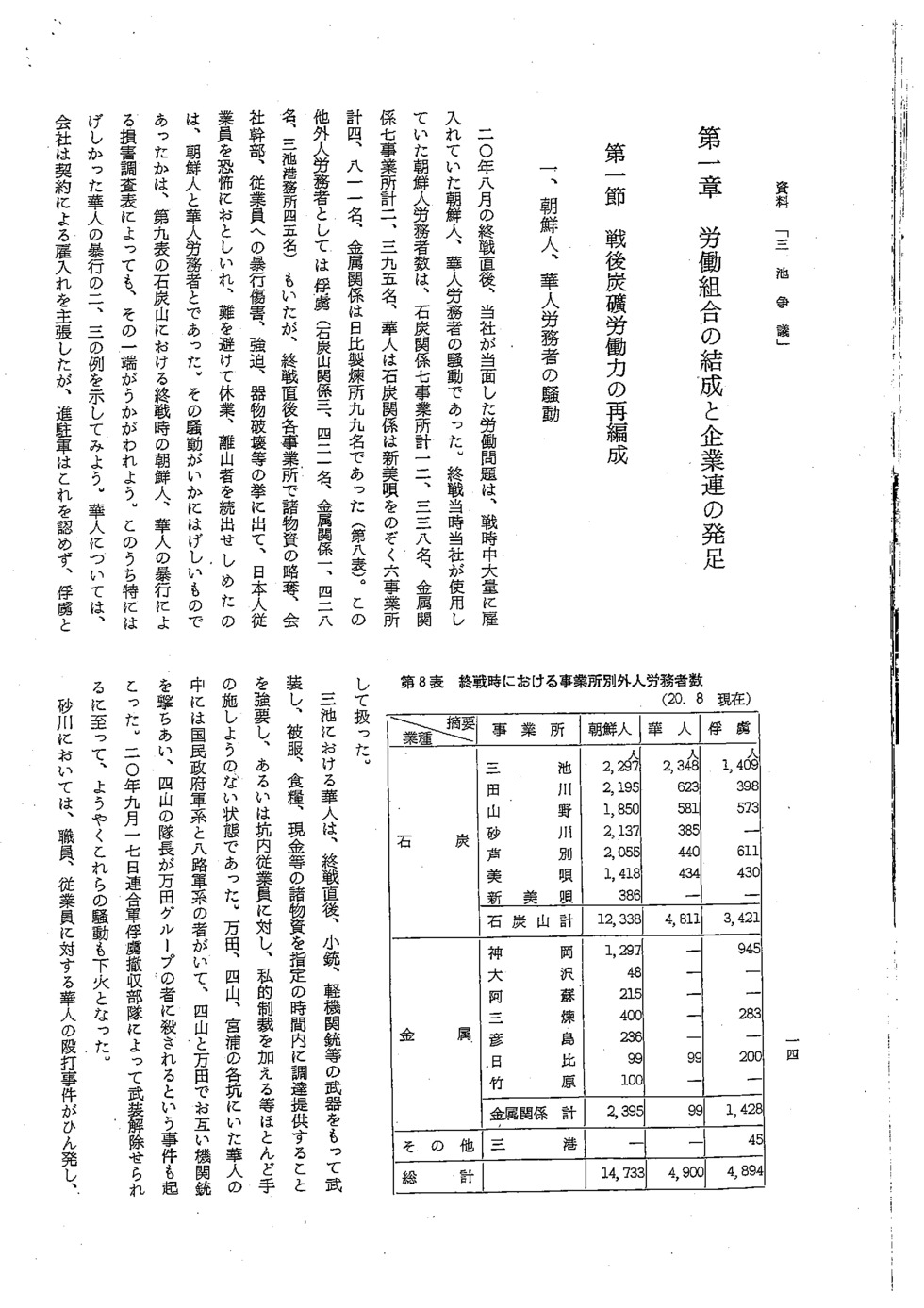

Table 9: Damage caused by Korean and Chinese violence in coal mines at the end of the war (created in January 1946)

|

Operation

Type of damage |

By nationality

|

Miike

|

Tagawa

|

Yamano

|

Sunagawa

|

Ashibetsu

|

Bibai

|

Shin-Bibai

|

|

Destruction of housing

|

Koreans Chinese

|

- 105,800 yen |

- - |

- - |

- - |

- - |

- - |

- - |

|

Destruction of fittings

|

Koreans Chinese |

5,365 yen 325,678 yen |

21,637 yen 28,087 yen |

13,200 yen 5,460 yen |

8,763 yen 11,191 yen |

21,300 yen 65,980 yen |

23,958 yen 72,730 yen |

2,987 yen - |

|

Futon destruction

|

Koreans Chinese |

11,540 yen 167,662 yen |

49,758 yen 286,507 yen |

43,000 yen 18,950 yen |

31,121 yen 101,236 yen |

37,660 yen 133,221 yen |

38,542 yen 183,675 yen |

10,406 yen - |

|

Injury

|

Koreans Chinese |

- 45,735 yen |

- - |

- - |

- 21,679 yen |

- - |

- 45,230 yen |

- - |

|

Total

|

Koreans Chinese |

16,905 yen 644,875 yen |

71,395 yen 314,594 yen |

56,200 yen 24,410 yen |

39,884 yen 134,107 yen |

58,960 yen 199,201 yen |

62,500 yen 301,635 yen |

13,395 yen |

Note: This table was created in January 1946 from materials presented to the Ministry of Finance by the Coal Control Association for the purposes of receiving national compensation for the amount of damages caused by unreasonable demands by Korean and Chinese workers at the end of the war.

With the imprisonment of the Bibai manager in particular, a 500-member police unit along with a 350-member civil defense unit failed to suppress the situation, which was only finally contained by the Occupation Forces. On September 24, 1945, a violent incident resulting in injury and death occurred whereby around 140 Chinese at Bibai attacked the dormitory at the Mitsubishi Oyubari coal mine, and struck and killed a Chinese unit head and another person who tried to stop them, as well as seriously injuring several police officers. On September 26, the prefectural police came in and arrested around 100 Chinese. However, military police from the Occupation Forces asked the prefectural police to release the Chinese, saying that they would crack down to ensure that a similar situation did not occur again, and suggesting that if the violence continued regardless, the Japanese police could act as they saw fit. The local authorities therefore had no choice but to release the Chinese. However, after they were released, the Chinese became very arrogant and started robbing and attacking people as they saw fit. They also lied to the police, saying that at the time of the mass arrest, they had lost a lot of their money, clothing, shoes, watches, etc., and demanding that these be returned. On October 2, they invited the Bibai assistant police inspector to the Chinese dormitory and demanded that all these lost possessions be returned immediately, keeping him at the dormitory all night. On October 3, they called the Bibai manager to their unit head’s room at the dormitory to demand that the company supply them with the goods immediately, keeping him tied up there for 21 hours from 11 in the morning that day until eight the next morning. In the end, the company and the police both supplied the goods that the Chinese were demanding, bringing the situation to a close.

As for metal-related operations, only the Hibi smelter used Chinese labor, but partly because there were not many Chinese, the situation remained calm from the end of the war through to the repatriation of these workers on October 10. However, on October 10, after the Chinese were put on board a ship at Tama Port ready for departure, they had to disembark again because of an engine failure, and, as in the saying “one loses all one’s inhibitions when away from home,” they grabbed weapons and staged a demonstration, invading local alcohol and sweets stores, etc., stealing goods, and blocking streets, as well as demanding that the company give them money for the return home in cash immediately. The company had no choice but to give in to their demands.

These are examples of violence and robbery by Chinese in particular. There were far fewer incidents of violence, robbery, etc., by the Koreans, who were employed for a comparatively long time, but the fact that there were incidents of violence involving Koreans at the various premises can be deduced from Table 9. While it is not noted in that table, here I will describe some incidents at Ashibetsu.

The first was a dispute between Koreans and Chinese at Ashibetsu. At the end of the war, there were more than 2,000 Korean workers at Ashibetsu and around 450 Chinese workers (Table 8). Of these, the Koreans had been brought in at the beginning of the Pacific War, with many becoming quite skilled workers, and during the war the company had created a restaurant for these Korean workers near Ashibetsu Kogyosho. There, Koreans who had demonstrated excellent work efficiency could exchange coupons to buy meals, etc. When the war ended, however, Chinese workers who were unable to use the restaurant and who felt that this was discriminatory treatment went in uninvited and demanded that they be allowed to use the facility. The Koreans refused to let them, and as a result, in the evening of September 22, 1945, all the Chinese and all the Koreans gathered to engage in a moonlight battle across the Ashibetsu River. Armed with sticks, stones, etc., both sides continued to wage war for over two hours, with each suffering one fatality and dozens of injuries.

While this was a fight between the Koreans and the Chinese, there was also an incident involving injury and death amongst Koreans. There were more southern Koreans than northern Koreans at Ashibetsu. Some of the northern Koreans were scheduled to return home ahead of the others, and to prevent the remaining northern Koreans from being mistreated by the southern Korean majority, they decided to make an example of key southern Koreans before they left. In mid-December 1945, they ordered around 1,000 knives and other blades from the local blacksmith and spent several days going in search of the southern Korean unit head and other leaders in the mountains and taking them naked in broad daylight to the front of the local police box, where they beat the unit head to death right in front of the branch manager, while also seriously injuring several other southern Koreans.

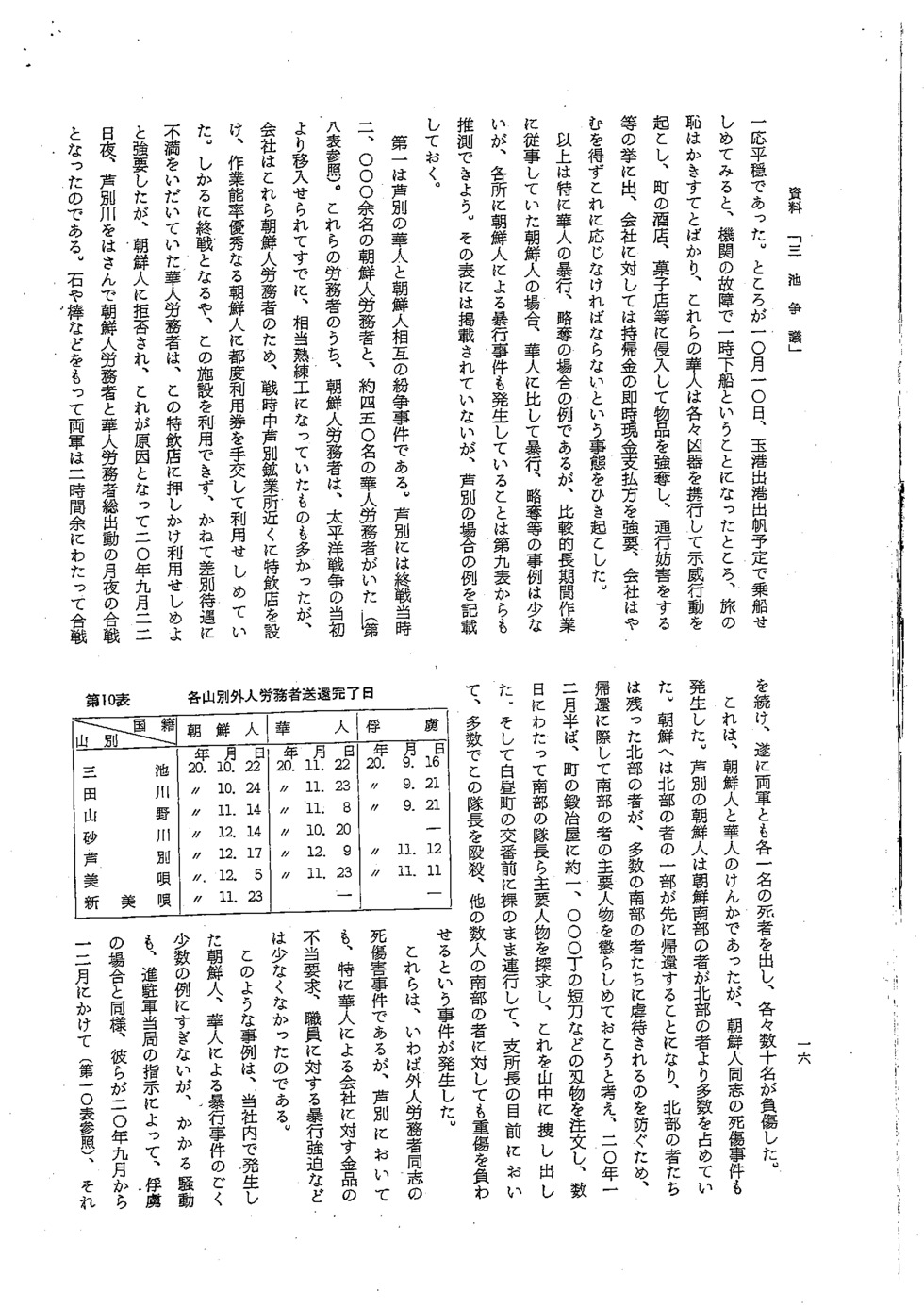

Table 10: Day of completion of repatriation of foreign workers by mine

|

Nationality |

Koreans |

Chinese |

Prisoners of war |

|

Mine |

|||

|

Miike |

Oct. 22, 1945 |

Nov. 22, 1945 |

Sep. 16, 1945 |

|

Tagawa |

Oct. 24, 1945 |

Nov. 23, 1945 |

Sep. 21, 1945 |

|

Yamano |

Nov. 14, 1945 |

Nov. 8, 1945 |

Sep. 21, 1945 |

|

Sunagawa |

Dec. 14, 1945 |

Oct. 20, 1945 |

|

|

Ashibetsu |

Dec. 17, 1945 |

Dec. 9, 1945 |

Nov. 12, 1945 |

|

Bibai |

Dec. 5, 1945 |

Nov. 23, 1945 |

Nov. 11, 1945 |

|

Shin-Bibai |

Nov. 23, 1945 |

|

|

These were incidents of injury and death caused amongst foreign workers, but at Ashibetsu too, there were also numerous incidents of Chinese in particular making illicit demands to the company for money and goods or threatening or physically abusing staff members.

The above are just a few examples of incidents of violence by Koreans and Chinese within the company, but in each case, as with incidents involving prisoners of war, they were all extracted from company operations from September through December 1945 at the direction of the Occupation Forces (Table 10) and sent home, bringing an end to the situation. It was a memorable sight to see Chinese who had arrived at the mine thin and weak and carrying a single blanket apiece going home fat and round and staggering under huge loads of pillaged goods.

[1] The bunkhouse system and other similar systems were abolished at Mitsui as follows. Tagawa: In 1900, when Mitsui took over management of the mine, there were four bunkhouse foremen, but the system was abolished in 1902 and replaced with ukeoi meiginin (registered contractors), a system which was in turn abolished in 1930. Yamano: In around 1901, a bunkhouse caretaker system which was effectively a bunkhouse system was instituted and eight caretakers (naya sewayaku) appointed, but with the formation of the kyoai kumiai (factory councils) in 1920, this was completely abolished. Miike: After the government sold the Miike mine to Mitsui, a similar system was introduced by appointing several miner recruiting contractors. This system was used alongside the direct control system, but it was totally abolished in 1908. Kamioka: A similar system called a hanba (kumi) system was introduced in around 1887, but completely abolished in 1926. Yumoto: A similar system called a kumicho system was totally abolished in 1924. Matsushima: The Matsushima coal mine bunkhouse system, said to embody the worst of the system, was totally abolished in 1923. While it was in operation, a total of 21 people were involved, comprising nine bunkhouse foremen, eight middle-level foremen, one foreman for coal putters, and three caretakers.

[2] Prison labor at Miike: In July 1873 when Miike was still government-operated, miners were virtually bought and sold, and the government used prison labor as miners at Miike. In 1889, when the government sold off the mine, the company struggled with recruiting miners in the same way as the government and got permission from the government to continue using the same prison labor from the government-operated years. At the time when the government sold the mine, there were 2,144 prisoners at Miike, comprising 1,463 from the Miike prison, 460 from the Fukuoka Prefecture Miike prison, and 231 from the Miike branch of the Kumamoto Prefecture prison. The periods during which prisoners were used at Miike and the number of prisoner coal diggers at each pit are as noted in Tables 3 and 4.