Mr. Mitsuoki Tsubouchi ② Long Interview

General Incorporated Foundation the National Congress of Industrial Heritage

Koko Kato, Managing Director

“We took flies and rats to the Company and they bought them from us.So even though we were kids, we could buy anything.”

Mr. Mitsuoki Tsubouchi, 87, currently lives in Tokyo. He is a person who has intimate knowledge of Hashima from during and after the war, until he moved to Tokyo in 1961. Over several interviews, he shared his memories of Hashima, including the relationships he had with workers from Korea. This is the extended version of the interview that I shared in my last column. His forceful storytelling was filled with humor.

Spending his youth on Hashima

――On Hashima, there were so many rats and cockroaches and flies. We would catch them and take them to the Company - and they would buy them from us. That’s how kids earned pocket money ――

――Tell me about your youth

“The Company bought the flies and rats. They would give us money for each of them. For the flies, they paid a certain amount for a bunch. I can’t remember how much they gave us for 100 flies. We would catch them and take them (to the Company).”

――They gave you money for your catch?

“Yes, they gave us money. We could buy anything with that money.”

――Were kids allowed to go into the pit?

“No, just on the outside, or above ground.”

――So you did this near the apartments?

“Yes. I’m trying to remember how long we did this for. I don’t think we did it for long. The rats were harder to catch, so we’d catch a lot of flies and put them in a box and take them (to the Company).”

Entertainment on Hashima――Movies, Pachinko――

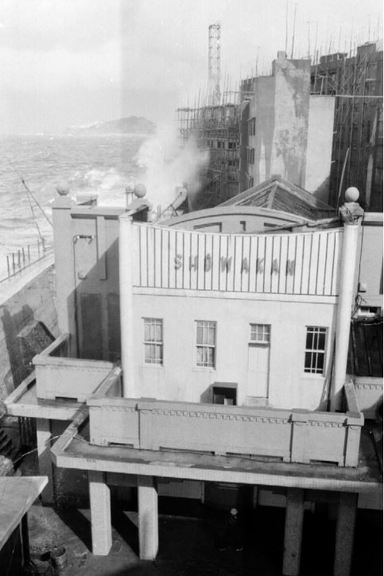

――I heard you worked at Showa-kan (movie theater). Can you tell me about entertainment on the island?

“I started working at Showa-kan in 1957. I am trying to remember how much I was paid then. I think it may have been 7,000 yen per month. The theater was always full.”

――Were they showing movies during the war?

“Yes.”

――You weren’t allowed in the theater, because you were a child, right?

“No, no kids. There were many movies we wanted to see. So we would go towards the end, and we would open the door. We would poke our heads in and look.”

――You were peeping (laugh). Were Korean people also in the audience?

“Yes, they could get in. It did’t matter who.”

――How frequently did the movies change?

“I think it was once a week. It changes almost every day. There were no Western movies during the war. They were all Japanese movies. But I think there was Tarzan”

Showa-kan (Year unknown)

――There was also a Pachinko parlor on the island?

“Yes, back then, there was a movie theater and a pachinko place. Pachinko and Smartball. Pachinko was a game for kids. Now it’s a grownup’s game. Back in our day, Pachinko was a game for kids.”

――Really? Pachinko was a game for kids?

“Yes. Nagata Store sold school suppplies, and Nakayama Store was the Pachinko place. They didn’t just have Pachinko. They also had Smartball, and they sold cigarettes. They mainly sold cigarettes. They just put a Pachiko machine there, and we played to kill time. There was also Kanegae Store (that sold household items) and a liquor store... The Pachinko machines weren’t electric. You used your thumb to snap the ball, like snap, snap (pachin, pachin). It was easy. The tulip cups would open, that kind of thing, but I wonder how long we played those for. It wasn’t that long. Then the grownups started playing and told the kids we can’t play anymore... it was like that.”

――Was the store owner running the pachinko operation?

“Yes, yes.”

――Was he taking money from the kids?

“I’m trying to remember how much he charged. I don’t think he charged that much. We were kids, afterall.”

――So it was a child’s game, back then.

“Yes, it was like that. So it must have been cheap.”

Nagata Store (Year unknown)

Bathing on Hashima

――What was bathing like on the island? Did each apartment have a bath?

“There was no bath in the Nikkyu Shataku (apartment for day laborers)”

――There wasn’t? Was there a communal bath?

“Yes, there was a communal bath”

――Were there Korean people there too?

“Yes. Since there was only one bath.”

――Everyone went there to take a bath? Was there discrimination?

“No. But freshwater bath was available only twice a week. On other days, it was sea water. Sea water was warmed up for baths.”

――Working in the coal mine must have covered you in soot. Where did you wash that off?

“So that’s why there is a bath right there.”

――There is a bath there? And you wash off there?

“You just jump right in. With your clothes on”

――With your clothes on?

“Yes, with your clothes on, and you wash everything”

――Japanese and Koreans all together?

“All together. That was the only bath there was.”

――So everyone goes in together? Everyone gets out of the pit and goes to the bath and washes off the soot? Your clothes and all?

“There were two bathtubs, separated. One is smaller, and if your clothes are really covered with soot, you wash your clothes in that one”

Tsubouchi-san shares his stories of Hashima

Chinese laborers on Hashima

――I heard that your father was fluent in Chinese, and that he was taking care of and supervising the Chinese workers. What kind of stories have you heard about the Chinese laborers?

“The Chinese people came and went together. They go there in the morning, and they would go home together, as a group”

“My father was the person responsible for the Chinese people, the Chinese laborers. There were about 150 of them”

――Were there kids that came from China?

“No, those Chinese workers, they all came alone”

――What do you think of the testimonies that were given that said “Chinese workers were only able to eat soy bean extracts”?

“What was the year we ate soy bean extracts...? It was before the end of the war. That’s when we couldn’t eat. It was the same for the Japanese people. There just wasn’t any food. I’m trying to remember when rationing started. We’d each get a certain amount of rice, for instance. So when you say they couldn’t eat, it was the same for us, since there was a shortage of goods”

――Was your father a pit supervisor?

“Yes, yes. He took them there”

――What did he say it was like?

“I don’t know what it was like. But after getting out of the pit, I saw him go to their dorm quite often”

――He went to the dorm? Who went to the dorm?

“My father”

――Your father went to the dorm to speak with the Chinese people?

“I think so yes. He would bring back Chinese bread when he came home. They would give those to him before he came home”

――Was there a dining hall for the Chinese people too?

“ Yes, there was a proper one”

――Where were they (the Chinese people)?

“ They were here. A wooden building was built for them next to Building #30”

Funerals on Hashima

――In 1938, when you were in 1st grade in primary school, I heard you held a funeral for your younger brother, who passed away at age three.

“Yes, this was when my father was away at the Sino-Japanese war. My younger brother, who was my second younger brother, who was just below my younger sister, died at age three”

――Where did you hold his funeral?

“Funerals were held at homes. The crematorium was in Nakanoshima”

――Do you take a boat to Nakanoshima?

“Yes, you row a boat”

――Everyone rows the boat?

“There was someone called a Sendo (boatman)”

――So the Sendo rows, and you place the casket on the boat?

“Wood. You load the boat with firewood and take it with you”

――So all of you, your family, rode together?

“We loaded the boat at the beach. Everyone who needed to go went”

――Did you go?

“I had to, because my father wasn’t there”

――So you had to go in his place. How did that make you feel? How long did it take on the rowboat?

“It didn’t take that long by boat. More than one person rowed. Two or three people (from the company) helped row the boat. So it didn’t take much time to get there. Maybe about 10 minutes. It was pretty fast. So we got off at the island, went to the crematorium, and stacked the big pieces of firewood, and placed the body on top. Then we placed more wood on top, the smaller pieces. We lit up the wood, and it was very quick. We didn’t use oil or electricity, like you do now.

――Did you take an urn there?

“You don’t. Once it begins to burn, you go home. Then you come back the next day”

――Did you go back to pick the bones the next day? You picked up the bones and put them in an urn and came home? Did the family members put the bones in the urn and bring him home?

“No, I went alone. No one else came”

――No one else came? You went alone? What about your mother?

“My mother didn’t come”

――How old were you at the time?

“I just entered primary school. So I was 7, because I was in 1st grade”

――How old was your brother?

“He was three”

――What did he die of?

“I wonder what it was. He just got a lot of bumps on his skin. The doctor came, just as he was supposed to”

――The doctor came to your house?

“I guess if it happened today, there’d be various ways to treat it”

――Your mother must have been shocked.

“There was another one that had just been born. My sister was born in 1937. She must have been about a year and a half”

――So you took your deceased brother on the boat to Nakanoshima, took him to the crematorium there, and then picked up his bones the next day and came home.

“You don’t pick up all the bones. There are some that remain. The remaining bones go to a hole a little further down. You throw them all away in there”

――I see. This is a story that was published in an article in a South German newspaper. I will read it again. (From the newspaper) “Forced laborers were made to suffer in Hashima, which was commonly called Gunkanjima. During the war, people of Japanese descent were moved to safe places and replaced by Chinese and Korean forced laborers. More than 1,000 people died on this island. The bodies of the deceased forced laborers were thrown into the ocean or abandoned mines.” Do you think the “abandoned mines” mentioned here is here?

“That’s not possible. There is no way!” (raises his voice)

“Since not all of the bones fit in the urn, there’s always some that remain. The remaining bones are buried there, all of them. They were all thrown in there. It did’t matter if they were Japanese or not”

――I wonder if the abandoned mine that they mention in the article is Nakanoshima.

“It must be, because there is no way they would throw them into the ocean”

――Does this mean, when bodies are cremated at the crematorium in Nakanoshima, the bones that did not fit into the urn were thrown away into the abandoned mine? Maybe the article embellished that fact.

“I think that is the case. Because you need to go the the crematorium to cremate the bodies. There was no crematorium on Hashima.

――So funerals are held at home, bodies are cremated on Nakanoshima, and the bones that don’t fit in the urn are placed in the abandoned mines.

“I think that’s right. Because there was no crematorium on Hashima, unless you throw them in the ocean. So I think the abandoned mine (the article mentions) is that. It can only be Nakanoshima. Because there was not a place on Hashima where you could throw away bones.”

Hashima after the Atomic Bomb

――Where were you when the atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki?

“We were playing. I was with my brother, downstairs. I was playing around here, near Building #65. I saw a flash and heard a blast. I looked up, and saw black, pitch black smoke come up.”

――Did windows of buildings break when that happened?

“No, they didn’t break. We were far away”

(Source:Based on “History of the Dissolution of the Gunkanjima Hashima Labor Union”, 1966, by Hashima Labor Union

After the long interview, on my way home, I realized that the sun had already set.

I remembered some of the things Tsubouchi-san had said in the interview. “Life on Hashima was good. If I had known, I would not have come to Tokyo”; “I ate roasted chestnuts that were sent from Korea with two classmates that came from the Korean Peninsula”; “When I was a child, I peeked into the movie theater towards the end of the movie”; “My brother died when I was in first grade in primary school. I took the body on a boat to the crematorium on Nakanoshima”. Without knowing, I was drawn into his stories. One more account of life on Hashima vividly came back to life.

Koko Kato

“Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” World Heritage Council Coordinator,

Sakubei Yamamoto Collection UNESCO Memory of the World Project Coordinator

“Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” Industry Project Team Coordinator

Author and Director of “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution Registration Recommendation Document”, “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution Registration Recommendation Document Digest”, and other official books, DVDs, and websites on the

Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution

Visiting Professor, University of Tsukuba (April 1 2015-March 31 2016)

Managing Director, National Congress of Industrial Heritage

Special Adviser to the Cabinet since July 2015.

Graduated from Keio University Faculty of Letters

Interpreter for international conferences, CBS News Tokyo HQ. MCRP, City and Regional Planning, Harvard Kennedy School; started own company in Japan.