When Did Korean Miners Become Victims?– The Trajectory of a Hundred Years

Classification Code: 1-10-04-001 1-02-04-001 1-03-04-001 1-04-04-001 ・-01-04-001

Publication Year: 2017

Commentary on articles appearing in major newspapers during prewar and postwar years, and various other publications

Author: Chung Daekyun

- Author

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

When Did Korean Miners Become Victims?

– The Trajectory of a Hundred Years

Chung Daekyun

Emeritus Professor, Tokyo Metropolitan University

- Articles Appearing in Prewar Newspapers

In recent years, Korean miners who worked in wartime mines are frequently being depicted as “forced labor” and “victims.” Particularly noteworthy is the children’s story recently published by 尹ムニョンYun Mun-yeong entitled Gunkanjima – hazukashii sekai bunka isan [Gunkanjima – shameful World Heritage site] (ウリ教育Uri Edu , 2016). This story contains the following passage from “Korean mine workers” in the age of comfort women and the “Statue of the Girl.”

- Gunkanjima – Shameful World Heritage Site

“Having started the war, Japan at the height of its folly carried away even young children from the Korean peninsula to force them into labor in Japan. The ソェドリ (Soedori= a reference to children, meaning “iron ”) were not even told where they were going. But their destination was the hell-like island of Gunkan-jima. The young children were taken down tunnels to depths of 1,000 meters to mine the coal that Japan needed to fight its war. The children were forced to work under conditions that resembled a steam bath where temperatures exceeded 45 degrees. They worked everyday for twelve hours and were given only a small rice ball to eat.”

What differences exist between the small children described in this passage and what the government of South Korea refers to as “forced labor?” The Investigative Commission of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Korea has published an English-language booklet entitled Stolen Country, Abducted People for preventing the registration of the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution as a World Heritage site. This booklet contains the following passage.

- Stolen Country, Abducted People

Under Japan’s wartime National Mobilization regime, people were treated as a form of material resource. Japan attempted to make up for its labor shortage by supplementing its workforce with labor from “colonial Korea.” As a result, many Koreans were forcibly deployed in the expansion of military industries and rice agriculture. These workers were deployed under series of systems referred to as “recruitment,” “government intermediation,” “conscription” and “patriotic labor service.” Their areas of deployment covered vast geographic regions and included the industrial districts of northern Korean, Japan, Manchuria, China and the South Pacific.

Korean workers were assigned to jobs that Japanese workers avoided, which generally meant dangerous work that posed a risk to life. In this way, Korean workers were forced to suffer both ethnic discrimination and deplorable working conditions. While they were forced to labor under unbearable conditions, the pay that Korean workers received was subject to forced savings. Japan has yet to settle these accounts.

Photographs: Family photo found on the body of a dead worker in Japan’s Chikuho Coalmines

Miner lies on his back while using a pick to mine coal

Japanese official encouraging a group of Koreans gathered at government office to apply for “conscripted labor”

Photo 1 of “young children” eloquently conveys the pitiable status of victims. Both photo 1 and 2 portray “Japan – The Evil Empire.” Normally, “Japan – The Evil Empire” is referred to as “Japanese imperialism.” The “Japanese imperialism” that Koreans talk about today is a projection of the “dark shadows” that persist in the hearts of the Korean people. The “evil” and “negation” of Japan and the Japanese are exaggerated to an excessive degree. The image that emerges of Japan is not the product of normal personal interactions and experiences involving Japan.

It should be noted that even in South Korea, Korean miners were not previously viewed as “innocent victims.” In this section, we first present an overview of how Korean miners deployed in the Japanese “homeland” were depicted in prewar newspapers. The sources used are primarily daily newspapers published in Korea (Korean newspapers and government newspapers). In the second half of this section, we present an overview of how prewar Korean miners are depicted as remembered in postwar books published in South Korea and Japan. An effort is also made to trace the development of a couple of narratives that have emerged in South Korea. We will start with an article that appeared in a Korean newspaper on the subject of Korean miners working in the Hashima Coalmine and other offshore coal mines of Nagasaki Prefecture. This is probably the first major article on the subject to appear in prewar Korean newspapers.

- “Korean Village Near Nagasaki” (Dong-a Ilbo, June 8, 1922)

This reporter headed out one afternoon to Takashima Village near Nagasaki City to observe the conditions in the Mitsubishi Mining Company where about 500 Koreans are employed. I boarded a ship and sailed out to a distance of about 50 ri in the Korean measurement of distance [ri = 400 meters]. What first entered my sight were the plumes of smoke rising from the coalmines of this green and verdant island. About 170 Koreans live on this island. Housing is not a problem as all are accommodated in company housing. One good day of work earns 2 yen in wages. Food is provided by the company at a cost of 40 sen (=0.4 yen) per day and clothing is not a major expense as all are laborers. An industrious worker can even manage to save some money. It is said that after working here for two or three years, some workers are able to save about 500 – 600 yen, which they have sent back home. Among the workers that have brought they wives and children with them, some of the sons have been enrolled in primary school. The children have earned high marks and are particularly gifted in languages. Children around the age of ten can be seen speaking fluent Japanese and translating for their mothers.

Advancing a little further out from Takashima Village, one arrives at an island known as Futago Island where nearly 200 Korean miners live. The standard of living is the same as that in Takashima Village. A further 10 ri out in Korean measurement lies a small island that is only about 10,000 tsubo in total area. About 180 Korean workers live and work here. During the day, they toil in coalmine shafts that are about 100 hiro in depth [hiro = the distance between outstretched arms], and at night they return to their company housing to sleep. Several families live in their own houses that are situated apart from company housing. In these homes, Korean women dressed in chima jeogori are seen preparing food. During the day, [the men] work at depths of 300 shaku [90.9 meters] mining for coal in dangerous mineshafts, and nights are spent listening to the lonesome sound of the vast ocean.

What goes through the minds of these workers living so far from home? The mineworkers I spoke to shared these thoughts. “Some say that living in foreign lands is unbearable. But for us, the time here passes very quickly. Although six years have already passed, it’s as though I arrived here a few days ago. Korea has probably changed a lot. Many schools have been built and there are many students now. When letters arrive from friends back home, they contain really happy news. If you work hard here, food is not a worry. Back in Korea, I could not stand the abuse by policemen. But here, abuse does not happen. All the children are enrolled in primary school. They speak good Japanese but their Korean is poor. So, we try to speak as much as possible in Korean at home. Those who earn 2 yen per day are those who work inside the mineshafts. Those who work outside earn only 1.20 – 1.30 yen.”

The largest number of workers here are from South and North Gyeongsang Provinces. The next largest group is from South and North Jeolla Provinces. There is almost no one here from Gyeonngi Province. Many of the workers return home after saving several hundred yen. These are people who came here because life back at home was difficult. Nevertheless, an indescribable ray of sadness covers the faces of these men who work in mineshafts during the day and spend the evenings reminiscing about the past as the waves repeat their gloomy rhythm.

The remainder of this section covers articles on Korean workers that appeared in Korean newspapers in the 1920s and 1930s prior to the start of planned mobilization. The question of interest is whether these articles show any evidence of narratives that refer to “Japan–The Evil Empire” or “victims.”

- “Korean Flood Relief Fund” (Busan Ilbo, September 2, 1925)

Names of Korean compatriots working at Nagasaki’s Takashima Coalmine who contributed 434 yen to Korean flood relief. [Omitted]

- “More than 90 Stowaways Caught” (Dong-a Ilbo, May 5, 1932)

李漣九、鄲澆学、徐貼淑、李基守 (Ri Jong-gu, Gwak Gyeong-hak, Seo Jeom-suk, Ri Gi-su) and four others from Beomil-dong in Busan have been arrested for conspiring to smuggle laborers to Japan. The group gathered 83 workers and charged them 12 yen per person for transport to Japan. On the night of the first, the laborers were discovered by the Maritime Police as they were departing for Japan on two motorized boats from 甘川里 (Gamcheon-ri) beach in Saha-myeon, Dongrae. The eight co-conspirators are currently being questioned but have already spent the more than 900 yen they had received from the 83 laborers. With no way to continue their voyage and no way to return, it is said the laborers are crying loudly in front of the police station.

- “A Rush of People” (Busan Ilbo, March 7, 1934)

All ferryboats are full of passengers and officers of the Ministry of Railways’ Busan Office are grinning widely with satisfaction. This heralds the age of fully booked passages to Japan. Korean workers who spent the lunar New Year at home are now returning to Japan. The number of passengers began to increase remarkably from four or five days ago so that the one ship that departs every night from Busan is no longer able to handle the traffic. On the 5th, some 300 people were unable to board and were diverted to the cargo ship Shokei Maru for passage to Japan. Pier One remains extremely crowded with people as this situation is expected to continue unabated for another couple of days.

- “44 Buried Alive in Burning Mineshaft–Disaster at Fukuoka Prefecture’s Yoshikuma Coalmine: 35 Koreans” (Maeil Sinbo, January 27, 1936)

On the 25th at around 11 a.m., a fire broke out in the Yoshikuma Coalmine in Kaho District, Fukuoka Prefecture. The fire started about 40 ken [72 meters] from a mineshaft to the east of the rest area. Of the total of 86 coalminers who were inside the shafts at the time, 42 escaped as the fire spread. However, 44 who were working in the lower levels at the time of the fire were unable to escape due to the heat of the fire and blockage of the passage. It is unknown whether they are alive or dead. Included among these workers are 35 Korean miners. The site of the fire was closed off and rescue efforts were started immediately. Air is being pumped into the mineshaft and every effort is being made to speed the rescue. However, no one appears to have been rescued as of 9 a.m. on the 26th. The cause of the fire is being investigated by the Chief Inspector of the Iizuka Police Department and numerous policemen. (“Fire in the Aso Yoshikuma Mine: 29 dead, 2 injured, most of whom who Korean miners” Chikuho sekitan kogyoshi nenpyo [Chronological history of Chikuho coalmining industry], p. 385)

On the other hand, there are some articles that plainly identify Koreans as victims and the Japanese as wrongdoers.

- “Money Saved from Toiling in Distant Land Stolen on Way Home–Unexpected Culprit was Crewmember” (Maeil Sinbo, June 18, 1936)

Bak Seong-beak朴ソンベク (age 22) of Goheung, South Jeolla Province travelled to Japan several years ago to work as a coalminer in the Iizuka Coalmines of Fukuoka Prefecture. Toiling long hours under foreign skies, Bak worked diligently and saved about 50 yen for his elderly parents back home. Carrying this money home, he arrived in Busan in the morning of the 16th aboard the Busan-Hakata ferry, the No. 2 Choho Maru. As he prepared his baggage for landing in Busan, he discovered that the money he kept in his pocket had been stolen. Shocked with the loss, Bak became pale.

After landing, Bak rushed to report the theft to the waterfront police station with jurisdiction. Officers immediately investigated the matter with full force. Kyoichi Mizuki (age 29), a crewmember of the Choho Maru, was arrested and confessed to the crime under questioning. The crime is considered to be serious and investigations are ongoing.

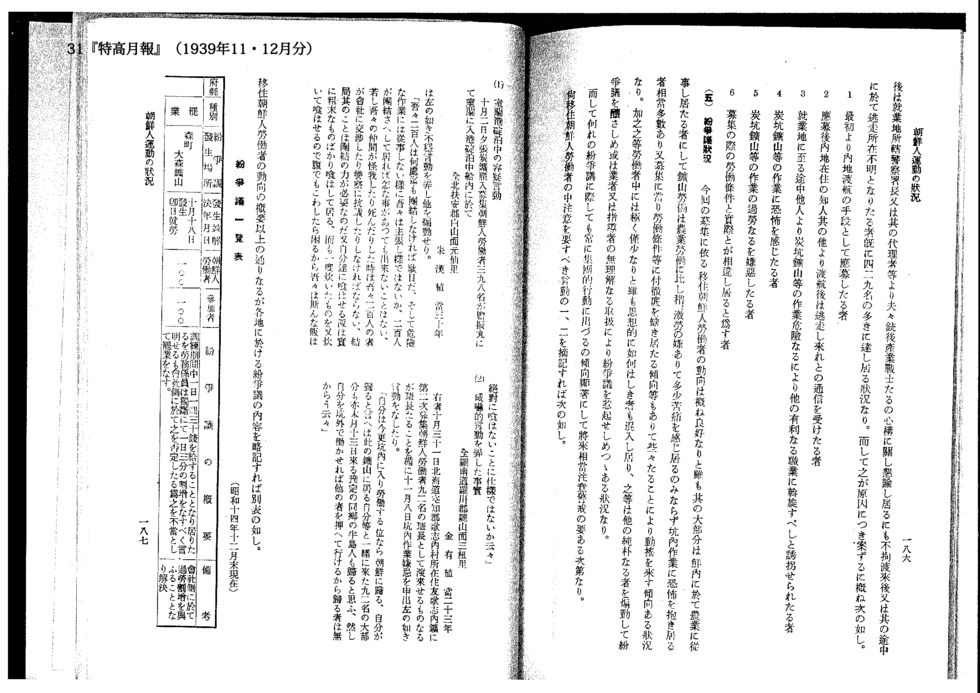

- Under the Manpower Mobilization Plan

In 1939, the government of Japan enacted the National General Mobilization Plan. This included a decision to deploy Korean workers in Japan’s key industrial sectors such as coalmining, metal mining and construction. The Mobilization Plan was a planned system of collective mobilization based on a wartime decision and act of the State. A total of 667,684 Korean workers were “transferred” to the Japanese homeland under the Mobilization Plan (Chosenjin shudan inyu jokyo shirabe [Survey of conditions of Korean collective transfer], Labor Bureau of the Ministry of Welfare, September 1945). The Mobilization Plan underwent the following three stages and ended at the conclusion of the war: mobilization through “free recruitment” (September 1939 – January 1942), mobilization through “government intermediation” (February 1942 – August 1944), and mobilization through “national conscription” (September 1944 – end of the war). The following are articles that were published in the media during this period.

- “Workers Bound for Kita-Kyushu–Large Numbers Leave Goheung on 28th” (Dong-a Ilbo, November 30, 1939)

Large numbers of workers have been recruited in the Goheung of South Jeolla Province for work in the coalmines of Kita-Kyushu. Led by guides, the workers departed Goheung on the 28th bound for their various places of deployment. For a time, the town was crowded with those who were leaving and the crowds that had come to see them off.

- “Outstanding Workers from Korean Peninsula to be Hired to Meet Human Resource Needs” (Nagasaki Nichi-nichi Shimbun, December 9, 1939)

Coalmines in Nagasaki Prefecture have been employing all available labor to expand output in line with the national policy on fuel and energy. A common problem among coalmines, however, has been the shortage of labor brought on by the general mobilization of human resources. This has made it increasingly difficult to meet production goals. No matter how loud recruiters raise their voices of “Come all workers!” recruitment has its limits because all surplus labor throughout the country has already been exhausted. When can we hope to solve the labor shortage in coalmines? Government authorities have been pursuing various measures to address this problem. Recently, the decision was made to transfer laborers from the Korean peninsula in line with the principle of “Japan-Korea harmonization.” Since late November, large numbers of reliable young people are being transferred to the Japanese homeland. The number of transferees has already reached 1,500. Through the intermediation of the Nagasaki Employment Office, these young workers have been deployed to ease the labor shortage in coalmines throughout the Kitamatsu coalfield, as well as in the coalmines of Seihi-Sakito, Hashima and Takashima. A sigh of relief is being heard in the coalmines.

- “Large Number of Workers Depart Changnyeong for Kaijima Mines” (Dong-a Ilbo, December 14, 1939)

A little while ago, a large number of farm workers from Changnyeong in South Gyeongsang Province were recruited to work for the Nittetsu Mining Company. On December 11, a second group left for Japan, many of them to work in the Kaijima Mines. In the midst of a sudden cold spell, the group was addressed in turn by the governor of the district and the chief of police. They were seen off by old parents and young wives and children who had gathered from distances of 20 to 30 ri. Brushing away the tears of their families, the young recruits piled onto several trucks and made their painful departure.

- “Large Number of Workers Depart Geochang for Mining Districts in Japan” (Dong-a Ilbo, February 17, 1940)

An increasing number of workers are leaving Geochang in South Gyeongsang Province to work in Manchuria and Japan. More recently, recruiters are coming directly from Japan to hire large numbers of workers. During a three-day period that began on the 13th, large numbers departed for mining districts in various areas. As a result, designated photo studios and barbershops were very busy. On the other hand, it was feared that there would be a shortage of farm workers.

The following are some articles covering the arrival of Korean mineworkers from the Japanese perspective.

- “Sending Money to Wife and Children Back Home–The Beautiful Virtues of Korean Peninsula People” (Hokkaido Times, November 25, 1939)

The people of the Korean peninsula are sweet people. For better or for worse, mining districts have become busier with their employment in coalmines. Those who say they are sly and cunning do so because of their own preconceptions. While some disputes have occurred, a little investigation has shown the sources of these disputes to be truly trivial. Now, all are working quietly and diligently. A troop of Korean workers gallantly heading for the mines in the morning sun outfitted in military rucksacks – yes indeed, they are all fine “industrial warriors”

The workers’ living quarters at Kamisunagawa is located at a short distance from the town and is called the No. 2 Oku-Shinwa Dormitory. When this reporter arrived at the scene, the miners were working in the mineshafts. The only ones present were a few in charge of the kitchen who were busy heating water and pickling radishes. These are people who cannot eat a meal without hot pepper and garlic. Mining companies are having a difficult time procuring these materials in sufficient quantities. A box lunch of rice comes with two thick red peppers, which the workers eat with nothing else to soften the spiciness. Pickled radish takes on a fiery red color with the addition of powdered pepper. But the workers eat this without giving it a second thought.

Japanese workers have complained to the company about the use of garlic. The pungent odor of garlic pervades the mineshafts and the Japanese don't like to work alongside Korean workers. When the company conveyed this complaint to them, a representative of the Korean workers bravely stated, “We too are citizens of Japan. So that we can work along side the people of Japan, we pledge to stop eating garlic.”

On the other hand, some articles carry stories of strikes and how Korean workers refused to go to work in the mines.

- “This Is Not What We Were Told–Refusing to Work in Mines” (Asahikawa Shimbun, November 1, 1939)

Workers from the Korean peninsula are playing a role in easing the labor shortage in coalmines throughout Hokkaido and have begun to work in the various coalmines of the Sorachi district since early October. The efficiency of these workers is being closely watched, not only by the mining companies that employ them but also by the Employment Department of the Hokkaido Prefectural Government and various employment offices throughout the district. About 300 Korean miners started working at the Mitsubishi Bibai Mines from the middle of this month and were divided into the No. 1 Troop and the No. 2 Troop and placed under the management of the mining department. Suddenly at around 6 a.m. of the 31st, the 150 members of the No. 1 Troop refused to enter the mine and remained outside throughout the morning. The company, which was taken aback, is discussing the matter with the person in charge of the No. 1 Troop in the hopes of returning the workers to the mineshaft. The cause of the trouble seems to be that the workers were not paid the level of wages that had been promised to them. It is thought that the 150 members of the No. 2 Troop will join their co-workers. The outcome is being closely watched by other workers in the mine.

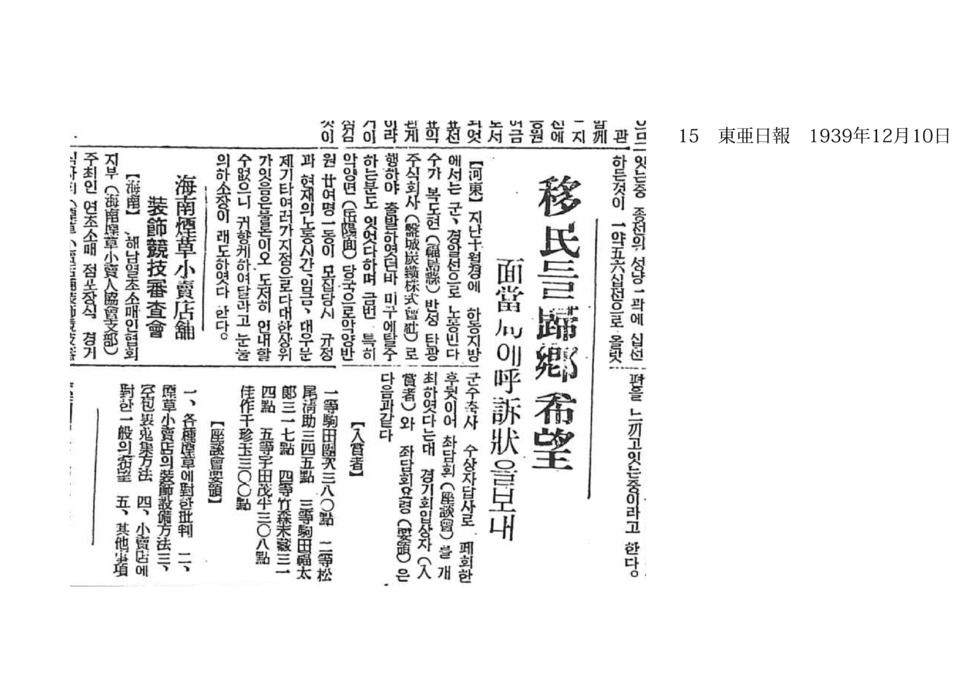

- “Immigrants Want to Return Home–Appeal Sent to Authorities” (Dong-a Ilbo, December 10, 1939)

[Hadong] On or around the 10th, a large number of workers departed the Hadong to work for the Iwaki Mining Company in Fukushima Prefecture. The workers had been recruited with the intermediation of the Army. It is reported that some of these workers have escaped. A group of about 20 workers have sent a tearful appeal to the authorities of Akyang-myeon asking to be returned home. Their complaint is that the terms and conditions promised when they were recruited are very different from the actual working conditions in terms of working hours, wages, treatment and other matters, and that these many differences are intolerable.

It should be noted that the period of manpower mobilization was also a period of rampant “human smuggling to the Japanese homeland” as described in the following articles.

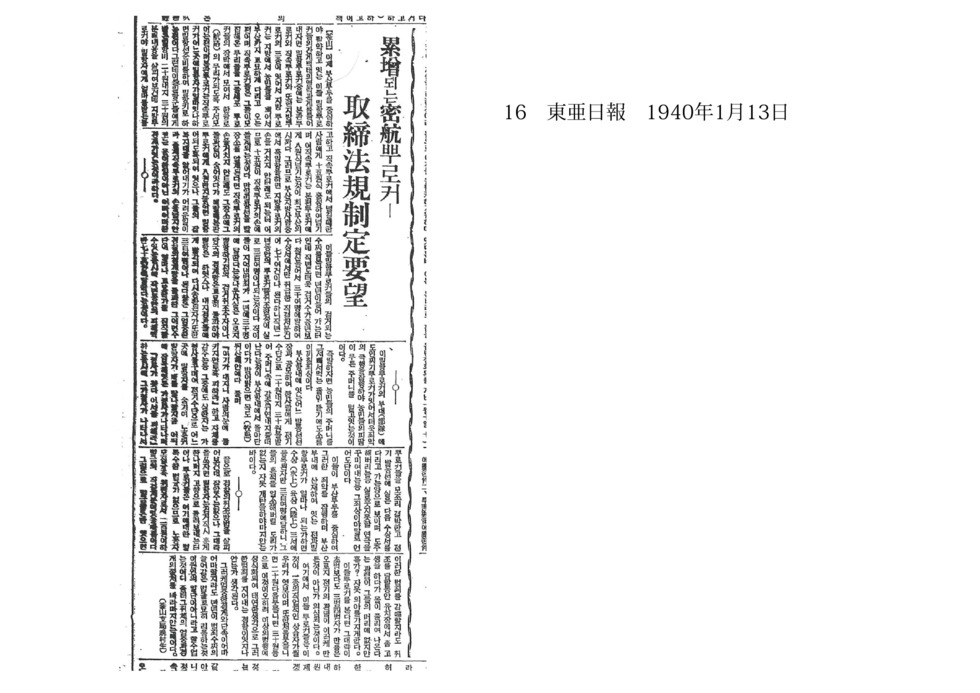

- “Increasing Number of Brokers Engaging in Human Smuggling” (Dong-a Ilbo, January 13, 1940)

Networks of about 100 human smugglers are currently active around the wharfs of Busan port. The brokers engaged in this human smuggling fall into three categories: primary brokers, brokers under the direct control of primary brokers, and local brokers working in the outlying regions. The role of local brokers is to trick local farm workers under various guises and to cleverly entice them to come to Busan. In Busan, the directly controlled brokers gather these workers inside the tent of their primary broker and put together the needed number of people for arranging passage to Japan. When the number of workers reaches a certain level, it is the job of the primary broker to make the necessary arrangements with smuggling vessels. The 20 – 30 yen collected from each worker to pay for the passage to Japan is divided in the following way. First of all, regardless of the amount he has received from each person he has recruited, the local broker pays a commission of 15 yen per person to the directly controlled broker. Next, the directly-controlled broker pays 8 yen per person to the primary broker. These are said to be the current going rates in Busan.

This means that someone living in Busan who wants to smuggle himself into Japan does not have to go through a local broker. All he has to do is to pay 15 yen to a directly controlled broker. Furthermore, if he knows where the smuggling vessel is departing from, he can hide in the tent with the others and pay 8 yen to the primary broker when he is boarding the vessel. However, because it is difficult to find these hideouts, it is said that it is not easy to bypass the directly controlled broker.

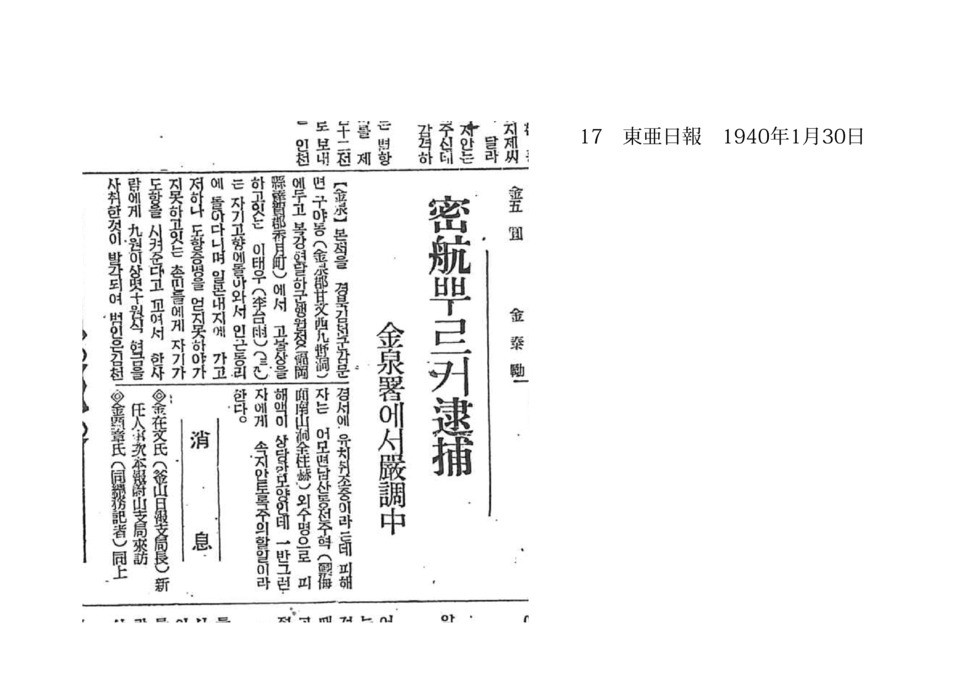

- “Smuggling Broker Arrested” (Dong-a Ilbo, January 30 1940)

李台雨(Yi Dae-u) (age 39) domiciled at Gimcheon, North Gyeongsang Province and currently operating a used goods business in Katsuki Town in Onga District, Fukuoka Prefecture, was arrested on charges of extracting payment for smuggling people to Japan. Returning to his hometown, Yi walked around the neighborhood offering to give passage to village people who wanted to go to Japan but did not have valid travel permits. Promising to deliver them to Japan, I received amounts of between 9 yen and several tens of yen from each person. I is currently being detained and questioned by the Gimcheon Police. Victims include 全栓赫(Jeon Ju-hyeok)and others. It is believed that payments made by the victims amount to a considerable sum.

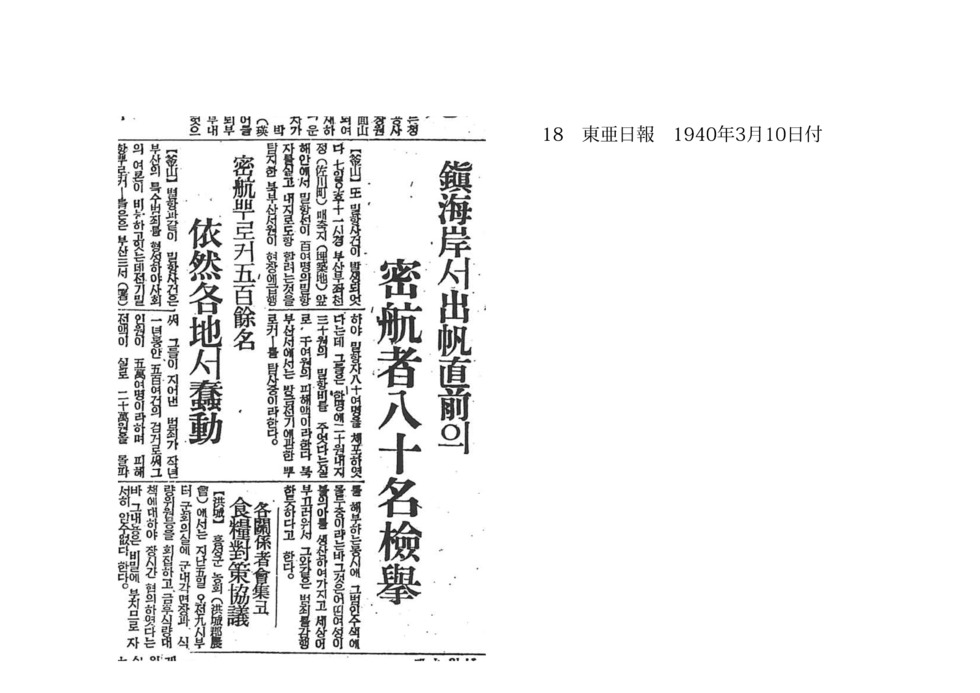

- “More than 500 Smuggling Brokers Remain Active in Various Areas” (Dong-a Ilbo, March 10, 1940)

Human smuggling constitutes a designated special crime in Busan and has engendered considerable public debate. According to information gathered by Busan’s three police stations, there are more than 500 smuggling brokers who remain active today. In the past year alone, criminal charges were filed in 500 cases involving a total of 50,000 people. The total amount of money paid by victims in these cases is said to exceed 200,000 yen.

- “Smuggling Brokers Arrested–Rigorous Questioning Continues at Mokpo Police Department” (Dong-a Ilbo, May 19, 1940)

A group of human smuggling brokers active in the inland areas of North Jeolla Province has been identified and arrested. According to informed sources, the brokers asked printing businesses to forge travel permits bearing the seal of the authorities. Several hundred people have been victimized and amounts paid by the victims are said to come to a total of about 3,000 yen. Other co-conspirators are said to be at large. [Note: Publication of Dong-a Ilbo was suspended in August 1940]

The following are articles that openly encourage going to Japan for work.

- “Special Treatment Offered for Korean Miners” (Osaka Asahi Shimbun: Central Korea Edition April 21, 1940)

The Nissan Mining Company in Mizumaki Town, Onga District, Fukuoka Prefecture, is hiring large numbers of Korean miners to increase coal production. The company has built new homes and apartments to provide special treatment to workers from Korea. In particular, the No. 1 and No. 2 Shokei Dormitories built for young and inexperienced workers from agricultural districts in southern Korea that have suffered crop damage provide hotel-like accommodations. Residents are excited about the excellent facilities. After ending a day of work in the mines, a group of miners gather during a quiet spring evening to enjoy the large communal bath brimming with hot water that would be unthinkable back home. The miners remember their families back home as they turn their eyes to the distant waters of the Genkai Sea.

- “The Unbelievable Income of Korean Miners” (Asahi Shimbun: South Korea Edition May 8, 1940)

Korean miners are earning big money as they toil like workhorses. Since last March, about 400 Korean miners have been working at the Nissan Onga No. 2 Takamatsu Coalmine in Mizumaki Town outside Wakamatsu City. The Korean workers belong to the mine’s Santo Training Center and are making a valiant effort every day to serve the nation through the production of coal. During the two months of March and April, these 400 workers remitted a total of 17,000 yen to their hometowns. Amazingly enough, it is anticipated that the total amount remitted will easily exceed 25,000 yen by the end of this month. In addition, the workers have accumulated a total of 12,000–13,000 yen in postal account savings, which far exceeds the company’s compulsory savings amount of 5,000 yen. The diligence and industriousness of the Korean workers can well serve as a model for Japanese mine workers. It is certain that they will play an important role in increasing the future output of coal.

Korean newspapers reported on statements made by the officials of the Government-General of Korea.

- “Improving the Quality of Korean Workers in Japan–Statement by Section Chief Hino of Gyeonggi Province Department of Social Affairs” (Dong-a Ilbo, April 5, 1940)

An inspection of the living conditions Korean workers in various regions of Japan organized by the Central Harmonization Commission of the Ministry of Welfare began on the 13th of last month. Participants consisted of 17 officials from the police and Department of Social Affairs from the seven provinces of southern Korea. The inspection was completed as scheduled and the participants returned to their posts on the 31st. Section Chief Hino of the Gyeonggi Province Department of Social Affairs, who served as the leader of the mission, made the following statement.

“Today, a total of 900,000 Korean workers [actual figure was approximately 1.2 million] are working in Japan. Compared to 310,000 workers in 1931, this represents a three-fold increase over a period of ten years. Among these 900,000 workers, 400,000 understand Japanese and 500,000 don’t. For this reason, the most urgent task on hand is to increase fluency in Japanese.

In the area of guidance counseling and instruction, many years of efforts have resulted in a marked decline in criminal activity. The crime rate ten years ago was 11 persons per 100, but has now been reduced to 4 per 100. While the number of persons coming to Japan has increased, the happiest news is that crime is continuing to decline from day to day. Although factories throughout Japan are welcoming Korean workers with open arms, there is a shortage of middle-echelon young people who can lead and instruct these workers. To address this problem, consideration is being given to establishing an institution in Korea for training such leaders. A training institute for Korean workers already exists in Kanagawa Prefecture and is reporting excellent results.

The spirit of patriotism is rising among Korean workers. They have already contributed the enormous amount of 250,000 yen since the promulgation of the New Order, and heartwarming stories are streaming in from all corners. The workers appear to have a keen interest in the issue of the adoption of Japanese names. However, because the procedures are complicated, the process of adopting a Japanese name is difficult to complete without returning to Korea. Consideration should be given to simplifying the procedural requirements.

The following article reports on relief funds sent by the Korean coalminers of Hashima to their hometowns suffering from crop damage.

- “Workers in Japan Contribute Funds to Drought Relief” (Dong-a Ilbo, June 19, 1940)

[Jinju] At the end of last year, a group of workers from Jinju went to work in the Hashima Coalmine of the Mitsubishi Takashima Mine in Nagasaki Prefecture. On the 17th, these workers sent a donation of 50 yen to the Jinju Government Office to help in drought relief. The result of diligent work and careful saving, the warmth and affection of the workers has truly moved the people of the town.

The following article reports on conditions at the Hashima Coalmine

- “Hellish Coalmines Exist only in Nightmares–On the Cutting Edge of Science” (Nagasaki Nichi-nichi Shimbun, February 28, 1941)

This reporter recently visited the Hashima Coalmine to hear the voices of volunteer workers contributing to increasing the production of coal. Having exchanged the sickle for the pick, these workers are using the agricultural off-season to diligently contribute to the achievement of national goals by burrowing deep into the earth where sunlight never reaches. The site of the coveted “black diamond” is an island shaped like a battleship that floats like a dream in the waters off Nagasaki Bay. More accurately, this is the island of Hashima designated as Takashima Village in Nishi-Sonogi District. The island is extremely small in area, and its population density is four times greater than that of Fukagawa in Tokyo. This is probably the most densely populated spot on earth. The amazing thing is that this entire island exists on the cutting edge of the world of science. The island is an hour and a half by ship from Oohato in Nagasaki. Upon arrival, the first things that surprise the visitor are the imposing ferro-concrete buildings that reach skyward. There are plenty of four and five story buildings, while Japan’s tallest, at nine stories, towers over the island.

Walking through a long tunnel, I arrive at Hashima Shrine and take a brief rest. Changing into work clothes, I am led into the coal shafts by Mr. Hyogo, the manager of the mine. For the ride to the bottom of the pit, I hop on an elevator capable of carrying 50 workers down to a depth of 2,000 shaku [600 meters]. The elevator descends at a speed of 40 shaku [12 meters] per second. But because the facility was build with no regard for budget, riders barely realize that they are on a descending elevator. People realize that they are descending when their ears pop on the way down. Arriving at a depth of 2,000 shaku, the air feels a bit damp but the area is as bright as noon with electric lamps burning bright. Streamlined electric trains are pulling coal-laden bins at amazing speed. The manager reminds me, “Fish are swimming above your head,” and I suddenly come to the realization that I am standing 2,000 shaku below the surface of the sea. I curiously take in the sites as we advance through a long shaft, finally arriving where workers are digging for coal. In common view of things, coalmining is automatically associated with handheld picks. But there is no place for that kind of traditional method here. Electric-powered picks are used to chip away at the coal vein. At first sight, the work appears to be simple but actually requires considerable skill because coal has to be extracted and removed while making sure that the mineshaft does not collapse. This is the responsibility of the lead digger. There are many others, each with his own responsibility. Some are seen feeding the coal into bins. Others are filling in the holes that have been left after coal has been extracted, constructing the shaft, or carrying coal away in wheelbarrows. Having observed all these processes, one gets the sense of the strenuous nature of the coalminer’s work. All the while, workers with blackened faces and bodies are working diligently to perform the duties assigned to them.

I hear the deafening roar of a dynamo and am told this is from the motor that drains the water that collects in the mineshaft. Standing in a hole that is 2,000 shaku deep, I experience no difficulty breathing and there is no trace of the scent of gas. This is all thanks to the excellent ventilating system that constantly feeds fresh air from the surface to these underground tunnels. Because the power of science is utilized in all aspects of the operation, there is absolutely no sense of fear or danger. Needless to say, the volunteer brigades s who have come to the mine with no previous experience are also happily performing their tasks. After my tour of the mine, Manager Hyogo says, “This was only a brief inspection, but I hope you have gained an appreciation for what our coalminers are doing. Also, I believe you have seen how this work is not the hellish work that it is often made out to be by the public. The faces of the workers are beaming with the hope that society will gain an accurate understanding of what coalmines are all about.” All these advances have dramatically changed and improved the life of the coalminer, and the barbaric conditions of the past are seen no more, even if one endeavors to look for them. No doubt, this owes much to the improvements made in recreational facilities and treatment of workers. However, the greatest cause of this change is the promulgation of the New Order. Responding to the Imperial Rule Assistance Movement, a Self-Governing Committee for the Implementation of the Path of Subjects was formed for the workers last December. Under the instruction of the committee’s subordinate organizations, workers are now engaged in autonomous programs for training and the development of character. These have recently garnered immense results in various areas. There has been a remarkable drop in work stoppages, people leaving their posts early, and workers applying to be transferred to other jobs. I was told that labor productivity at this mine was probably the highest in Japan.

This report contains an interesting statement made by Kinsaku Sakurai, a worker from Hiroshima who had worked in Hashima for many years.

- “Agricultural Off-Season Volunteer Workers–Reportage” (Nagasaki Nichi-nichi Shimbun, February 28, 1941)

“I have been working as a coalminer for 31 years. At first, I worked at Takashima. The pay was low and ranged from 48 sen (0.48 yen) to a maximum of 90 sen. The facilities were very poor and we were using primitive carrying-poles to transport the coal out of the shafts. My shoulder ached terribly, and if I said I could not work anymore, my co-workers would attack me with their fists. This happened more than a couple of time, and I passed the years in tears. Those who couldn't stand this punishing work environment would attempt to escape the island. They tied empty sake kegs to their body and tried to swim to shore when the guards were not looking. Later on, I moved to Hashima and have been here for 18 years. In the early years, Hashima also was no better than a prison cell and bloody fights were the order of the day. Hashima began to change into what it is today when the company started developing recreational facilities about 20 years ago… It’s true that many of the workers are here because they hold a grudge against society. They are thirsting for attention and love. So, if they are instructed with a warm heart, the barriers will come down faster than in a group of normal people. To reduce the constant transfer of workers, I am helping them settle down by introducing them to prospective wives. But the problem is that there are very few women on the island.”

With the start of the Pacific War in December 1941, Japan began to mobilize all of its resources for the war effort. During this period, many articles supporting the war effort appeared in Korean-language newspapers. The following article reports on a visit to Japan by Korean mineworkers.

- “Ten Outstanding Miners Selected–To be Dispatched to Japan” (Maeil Sinbo February 1, 1942)

The Gangwon Provincial Mining Federation has selected the following ten outstanding miners recognized for their excellent performance during the output strengthening period. They will be dispatched for a week to the Miike Coalmine in Fukuoka Prefecture, a high-performance mine in Japan, where they will observe mining conditions as wartime mining warriors. At the same time, they will perform volunteer work and visit several other high-performance mines (Niroo, Ikuno, Ashio and others) in each sector of the industry for periods of one to two days. This will be followed by pilgrimages to holy sites, such as Ise Shrine, Momoyama Imperial Tomb, Meiji Shrine and Yasukuni Shrine. These visits are intended to raise their awareness as Japanese and contribute to increasing coal output in Gangwon Province. The group will depart Chuncheon at the end of February and will return home in mid-March after completing their tour of 21 days. The cost of the tour will come to 150 yen per person, 100 yen of which will be subsidized by the Provincial Mining Federation. The tour is open to other mines that are willing to pay for the full cost of participation in the tour. The ten outstanding miners selected for the inspection tour are the following. [Omitted]

- “Unfazed by Brother’s Martyrdom in Line of Duty–The Fighting Spirit of Korean Workers” (Nagasaki Nippo, July 23, 1943)

Kosen Kanemoto (age 27) is a “mining warrior” from the Korean peninsula who works at Nippon Mining Company’s Yatake Coalmines in Kosasa Town of Kita-Matsuura District. On July 2, his younger brother, who was employed as a workhand, was killed in the line of duty. Brushing aside the recommendation of the company to return his brother’s remains to his hometown for burial, Kosen Kanemoto has continued to work extracting coal from the bowels of the earth without even a day of absence. Encouraged by his example of fighting spirit, his compatriots from the Korean peninsula have risen to new heights of commitment to their work. Kosen Kanemoto will soon be officially commended by the Ainoura Police Department to recognize him as a model worker for contributing to increased wartime coal production, reinforcing war capacity and for distinguished service to his occupation.

- “Application Written in Blood–The Sincerity of Korean Youth” (Nagasaki Nippo, September 28, 1943)

A Korean youth has volunteered for Special Naval Volunteer Service with an application written in blood. His application bearing the words, “We are the children of the Emperor and of the Japanese spirit,” was delivered from the Sakito Coalmine to the Prefectural Special Police. The applicant, Taichin Kanetake (age 17), was born in Yeongcheon, North Gyeonsang Province and is a Youth School (vocational school) second-year student living in the Sakito Coalmine No. 1 Shinwa Dormitory located in Sakito Town of Nishi-Sonogi District. Last March, Kanetake visited Sakito as an “industrial warrior” in the service of increasing coal production. He is now studying Japanese with a goal of joining the military. As soon as the introduction of the new systems for the conscription of Koreans into the Imperial Army and for Special Naval Volunteer Service were announced, Kanetake felt that he could not sit still for even a day as a Japanese citizen. Thus, in August, he submitted an application to the Youth School for transfer to Special Naval Volunteer Service. But for a variety of reasons, he was forced to give up his plan and returned home. However, with battles raging in the Solomon Islands, he felt he could not remain idle. On September 18, the anniversary of the Manchurian Incident, he cut the small finger on his right hand to write this message in blood, to which he attached his application for voluntary service and once again submitted it to the Youth School where he was enrolled. “We are the children of the Emperor and the spirit of Japan flows through the veins of Korean youth.” Moved by the sincerity and fervor of the applicant, the school decided to forward the application to the authorities.

- “I Will Continue to Work to the End” (Maeil Sinbo, May 5, 1944)

“I will continue to work diligently toward increasing coal production.” This is his oath, and with this oath he dedicates his life to the mine. These are the words of a young worker from the Korean peninsula who is committed to working diligently.

This is Kyuko Kanagawa, who works in the Kabo Coalfields. Kanagawa has completed his period of service and is now scheduled to return home. However, he says, “No, I will continue to work to the end.” With this pledge, he has remained in the coalmine and is continuing to work as diligently as before.

Kanagawa boasts the highest performance in the mine and constantly earns the highest wages. Over the past two years, he has sent 1,000 yen to his hometown. In addition, his savings amount to 800 yen. (This entire article was written in Japanese)

- “Kisaeng Entertainers Leave for Japan” (Maeil Sinbo, January 20, 1945)

Three troupes of kisaeng entertainers totaling some 20 women will soon be leaving to deliver the songs and dance of Korea to Korean industrial soldiers working in Japan. The purpose of the mission is to contribute to increasing the nation’s future war capacity. The mission is organized by the National Mobilization Federation and jointly sponsored by the Labor Mobilization Support Association, Coal Control Board, Japan Federation of Itinerant Entertainers [correctly, Japan Federation of Itinerant Theatrical Companies] and others, and will be leaving on the 25th. The tour will continue for a month and end on February 20. Two of the troupes will travel to Kyushu and the third will visit workers in Hokkaido. Led by Chief Examiner Tsuji of the National Mobilization Federation, the mission left Seoul on a train that departed at around 6:30 p.m. on the 18th. The names of the members of the mission are as follows. [Omitted]

What emerges from the above public statements and articles from the period of labor mobilization is a two-fold image. On one hand, one sees how Korean workers cooperated with the war effort and gradually increased their contribution to Japanese industries. On the other hand, there are occasional glimpses of resistance and protest from Korean workers. Examples of the latter are found in articles concerning Fukushima Prefecture’s Iwaki Coal Company and the Sorachi Coalmine. In the Iwaki case, contrary to allegations, it was determined that no significant difference existed between terms indicated at time of recruitment and actual work conditions. Notwithstanding this determination, the company was warned to pay greater attention to the treatment of workers. With regard to the Sorachi case, the Special Police Gazette (January 1939 issue) published by the Police Bureau of the Ministry of Home Affairs contains the following statement. “Under the direction of the police department with jurisdiction, the matter was resolved as caused by a misunderstanding.” Taking into consideration the fact that “human smuggling to the Japanese homeland” was widespread during the period of labor mobilization, it is clear that the presentation of Korean workers as victims and the expression “Japan – The Evil Empire” constitute new myths that were created after the end of the war through the collaboration of Japan and South Korea.

However, this does not mean that Korean people of this period did not harbor feelings of enmity and hatred toward Japan. In the next section, we explore the negative feelings that the Korean people had for Japan by reviewing articles appearing in the Special Police Gazette. The principal characters who appear in these articles are the political deviants and resisters of the period.

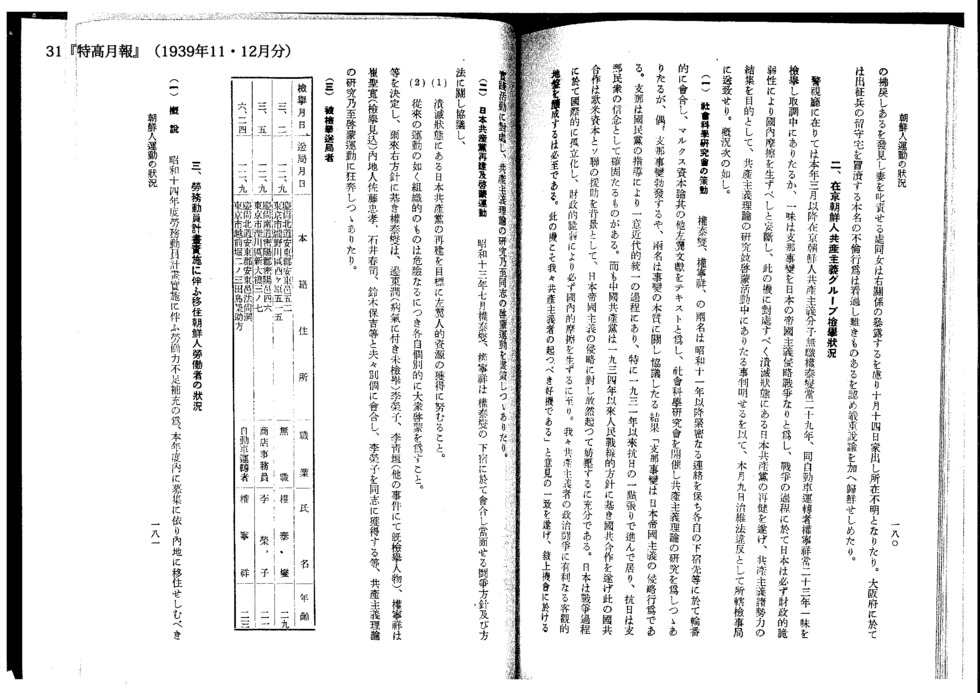

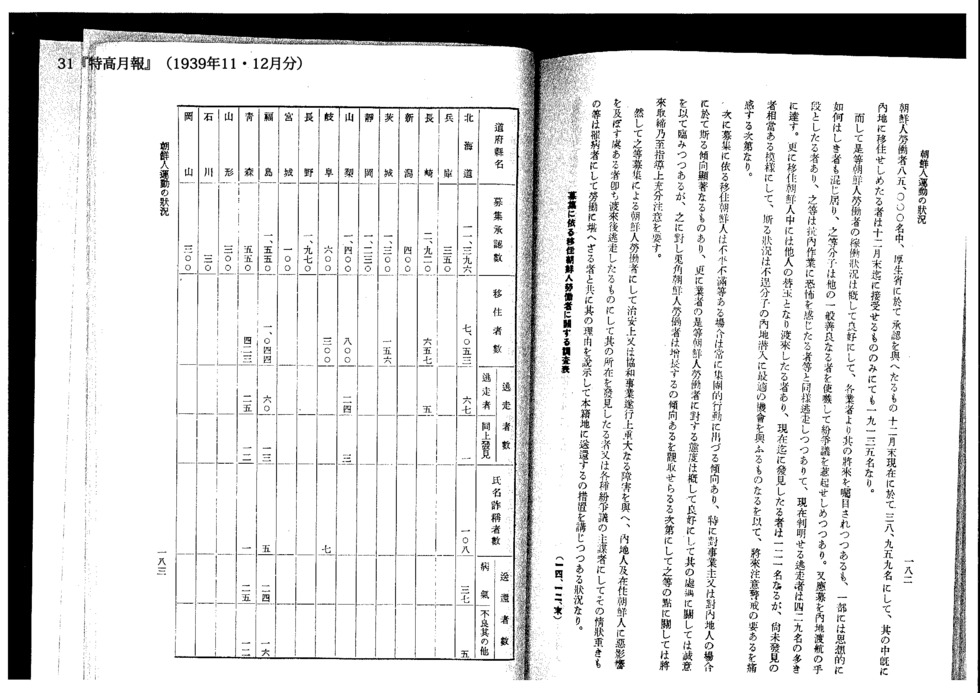

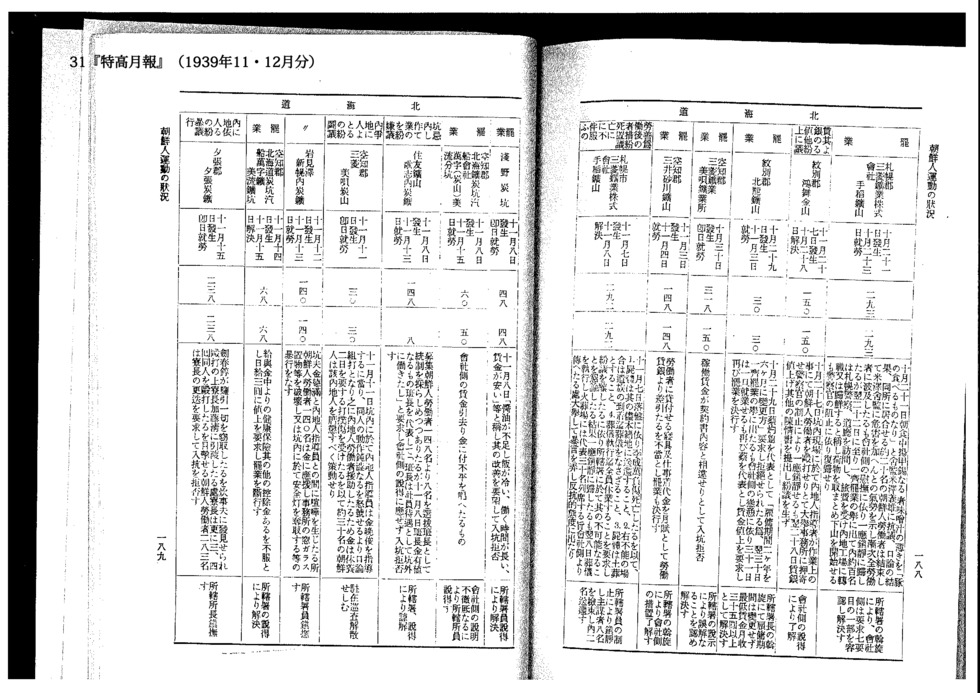

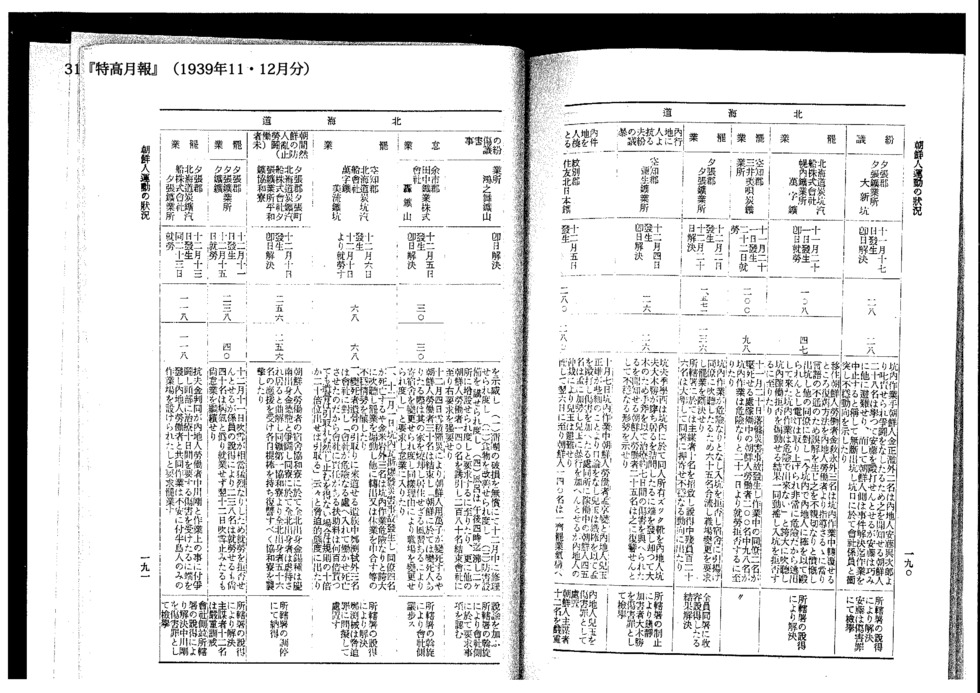

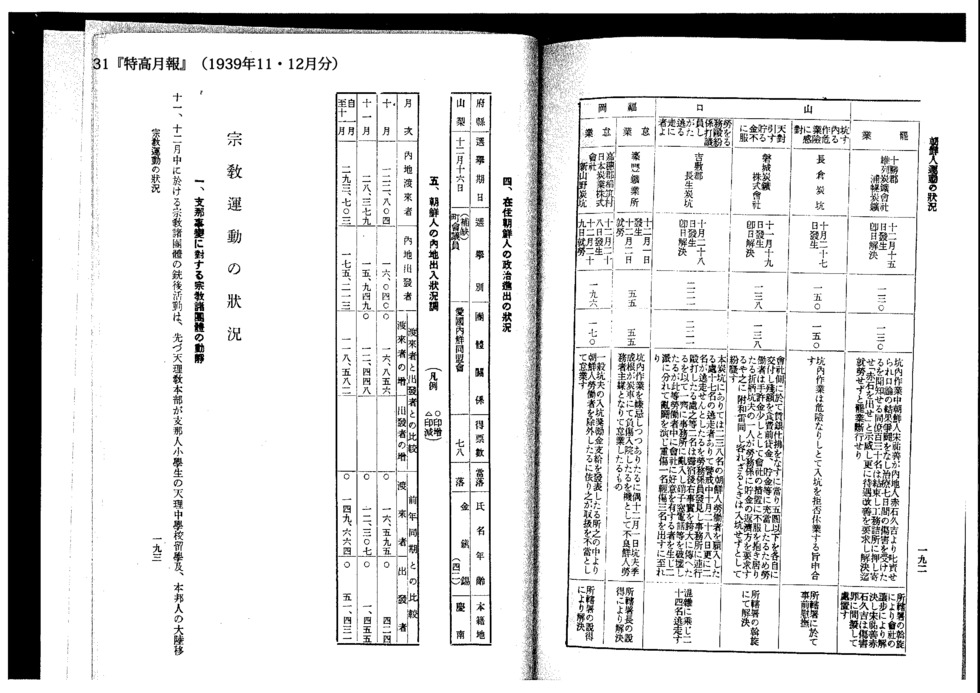

III. Articles Appearing in the Special Police Gazette

According to consecutive issues of the Special Police Gazette (November and December 1939) published a few months after the start of the labor mobilization program, the total number of Korean workers that had migrated to Japan as of the end of December 1939 came to 19,135 people. Of this total, 67 percent had been settled in Fukuoka and Hokkaido Prefectures. A section of the Rodo doin keikaku jisshi ni tomonau iju chosen-jin rodosha no jokyo [Conditions of immigrant Korean workers following implementation of labor mobilization] entitled “Summary” contains the following passage.

- Special Police Gazette (November and December 1939)

Thus, the work status of these Korean workers is generally good and various industries are looking with anticipation to their increased future role. However, persons of questionable ideology are mixed in with these workers, and these individuals are instigating protests and trouble by tricking other workers who are of good character. Also, some individuals are using the recruiting process as a means for immigrating to Japan. As in the case of workers who exhibit extreme fear of working in the mineshafts, these individuals are prone to escaping from their place of employment. Currently, a total of 429 escapees are known to the authorities. Moreover, among immigrant Korean workers in Japan, some have arrived by assuming the identities of others. To date, a total of 121 such individuals have been found. It is thought that many others have evaded detection so far. This situation provides ideal conditions for allowing outlaws and other unwanted persons to enter the Japanese homeland. In this regard, the need for greater future vigilance is keenly felt.

Immigrant Korean workers who have come to Japan through recruitment programs have a marked tendency to resort to collective action when they feel that they have been treated unfairly or when they are otherwise dissatisfied. This tendency is particularly strong when dealing with employers or with Japanese individuals. The attitude of employers toward Korean workers is generally good, and employers act in good faith in addressing problems that arise. However, it has been observed that Korean workers have a tendency to become excited and to grow impudent. This matter should be fully taken into consideration in the future implementation of control and instruction of Korean workers.

Among the Korean workers who have immigrated through the recruitment process, there are those who have a serious negative effect on public order and the implementation of joint enterprises. These are escapees. Whenever their place of residence is discovered or when they are found to be playing a leadership role in various types of disputes, those whose situation is considered to be serious are, together with the ailing and others unable to withstand the rigors of work, sent back to their place of origin with an explanation of the reasons for their removal.

Reading these documents, one becomes aware that various difficult problems existed from the beginning of the effort to mobilize Korean workers. While they were called “industrial warriors,” the fact is that to a certain degree the war was “someone else’s business” for them. Therefore, the sense of loyalty that they felt must have differed substantially from what existed in the heart of the Japanese. Problems related to nationalistic sentiment and cultural differences also must have been significant. The Special Police Gazette approaches these issues specifically from the perspective of Japanese police authorities. Nevertheless, these articles are a rich source of information on how Korean mineworkers interacted with the Japanese people and Japanese companies.

For example, Section 31 refers to “assumed identities.” The Special Police Gazette blames this problem on the group leaders responsible for transporting the workers to Japan and cites their following shortcomings: (1) many group leaders do not speak Korean, (2) due to unfamiliarity with Korean people, group leaders cannot properly determine the identity of the people they are transporting, (3) because each group leader overseas a large number of workers, they are not able to keep proper watch over the workers in their charge. Additionally, the Special Police Gazette reports that imposters are very clever in memorizing the place of origin, address, name, age and other particulars of the identities they are assuming.

This begs the question of what motivated these imposters. The Special Police Gazette states that migrating to Japan remained a “high aspiration” of many Korean people. Those unable to apply to a recruitment program smuggled themselves into Japan by mixing in with those who had been successfully recruited by “falsifying their name.” It is reported that the following methods were used by imposters to migrate to Japan: (1) receive a copy of the family registry of an individual who has given up on applying to recruitment programs, (2) assume the identity of a recruit who has failed to show up at roll call, (3) receive the copy of the family registry of a recruit who has a change of heart shortly before departing the train station or port.

As seen in the section on “brokers for human smuggling,” the period of labor mobilization was also the period of “human smuggling to the Japanese homeland.” However, many had smuggled themselves into Japan even before the start of labor mobilization. As of 1938, one year before the start of labor mobilization, 799,878 Koreans were residing in Japan. This number exceeds the 633,320 Japanese who were living in Korea in the same year. During this period, and particularly for young people living in southern Korea, the “Japanese homeland” presented an opportunity of a lifetime. In the pursuit of a better life, many Koreans attempted to migrate to Japan. Therefore, it is not at all surprising that some attempted to enter Japan under “assumed identities” and others would become “escapees” upon arrival. An article describing the reasons for escaping immediately states that some migrated to Japan with the express intent of escaping. The article identifies the following six types: (1) those who apply to recruitment as a means for migrating to Japan, (2) those who after applying for recruitment have received communications from friends and others already living in Japan encouraging them to escape after they arrive, (3) those on the way to their scheduled place of employment who are warned of the dangers of working in mines and are solicited to work in more advantageous jobs, (4) those who develop a debilitating fear of working in mines, (5) those who decide to avoid the strenuousness of working in mines, (6) those who find that the terms promised them at recruitment differ from actual work conditions. It is interesting to note that at this early stage of labor mobilization, the total number of escapees is reported to be 429. This figure increases dramatically during the periods of government intermediation and conscription. The Special Police Gazette provides the following data on escapees as of December 1943. Of a total of 146,938 workers brought to Japan under “recruitment,” 58,598 had escaped, and of a total of 219,526 brought under “government intermediation,” 60,137 had escaped. These figures perhaps reflect the difference between Koreans who are quick to seize an opportunity and Japanese who are diligent and restrained by the pressures of conformity.

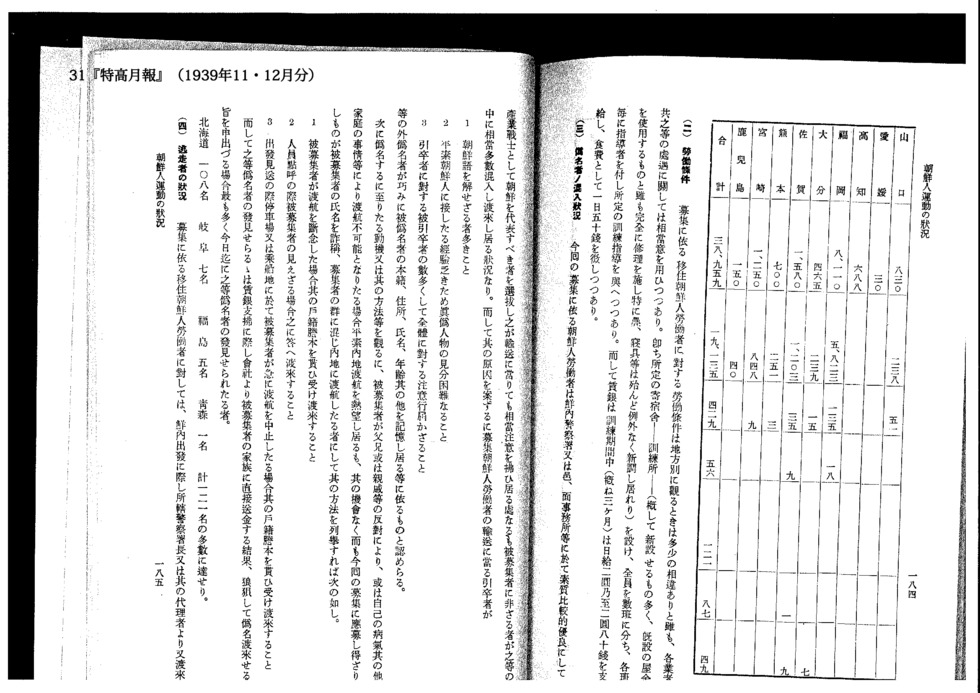

The November and December issues of the Special Police Gazette contain a “Table of Disputes” related to “immigrant Korean workers.” The information contained in this table provides a very interesting view of what immigrant Korean workers were actually experiencing in their workplaces. “Disputes” fall under a number of categories that include “labor strikes,” “disputes related to demands for higher wages,” “conflicts with Japanese people,” “assaults by Japanese people,” and “work slowdowns.” A total of 31 cases are described, of which 26 cases relate to Hokkaido. Although the data may be geographically skewed, these cases are an excellent source of information on what was actually taking place between Korean miners and Japanese people during this period. In the following section, a total of 15 cases are presented. Preference was given to cases that contain references to cultural friction and cases that contain relatively clear descriptions of the background of the dispute. These are all cases that occurred between October and December 1939. (Matters related to cultural friction are underlined.)

- Sapporo Mitsubishi Mining Company, Teine Mine (Participants: 293, all of whom were Korean workers)

During breakfast on October 21, a worker named 楊甲錫 (Yang Gap-seok) complained to Dormitory Master Yoshio Yonezawa that the miso soup was so thin that it was only “fit to be fed to pigs.” Following an argument, about 20 Korean workers living in this facility came together and threatened to harm Dormitory Master Yonezawa. The movement gradually grew to include all the Korean workers at the mine. Matters temporarily quieted down with efforts made by the company to calm the situation. However, on the following day, October 22, the workers staged a strike. About 100 of these workers declared that they would go to the Sapporo Police Department or the Hokkaido Prefectural Government to demand travel money for transfer to other workplaces in Japan or to return home to Korea. These workers gathered their belongings and began to leave the mine. However, they were stopped by police and returned to their workplace. (The authorities mediated a settlement in which the company accepted some of the seven demands made by the workers.)

- Sapporo District Mitsubishi Mining Company, Teine Mine (Participants: 292, all of whom were Korean workers)

On November 7, a worker named 李成万(Yi Seong-man) was killed in a cave-in accident. The workers then demanded the following: (1) that the body be returned to the worker’s hometown in its present form, (2) that if the preceding is not possible, then the funeral be delayed until the arrival of the dead worker’s family, (3) that the body be buried and not cremated, (4) that all workers be allowed to stop work until after the funeral. This developed into a dispute, which temporarily settled down with explanations given by the authorities that the demands could not be met. The company announced that the funeral would be held on the following day, November 8, and that 30 representatives of the workers would be permitted to accompany the body to the crematorium. The workers protested loudly and boisterously and showed a rebellious attitude. (The authorities intervened to control the situation, as a result of which eight leaders were arrested, of whom two were sent home.)

- Asano Coalmine (Participants: 48, all of whom were Korean workers)

On November 8, workers complained that, “There is not enough soy sauce and the rice is cold. Working hours are too long and wages are too low.” Demanding that conditions be improved, the workers refused to go to the mines. (The situation was settled with the persuasion of the authorities.)

- Sumitomo Mining Company, Utashinai Coalmine (Participants: 8 out of a total of 148 Korean workers)

To improve the management of workers, eight workers were selected from among 148 recruited Korean workers to act as group leaders. On November 8, a group leader named 金有植 (Kim Yu-sik) acting as the representative of the eight group leaders demanded that, “Group leaders should be treated formally as company employees and be allowed to work outside the mines.” The group leaders did not respond to the company’s explanations and refused to return to the mines. (The situation was settled with the persuasion of the authorities.)

- Sorachi District, Mitsubishi Bibai Coalmine (Participants: 30, all of whom were Korean workers)

On November 11, a Japanese instructor was instructing a worker named 金晩俊(Kim Man-jun). Angered by the worker’s slowness, the instructor yelled at the worker. The two then argued and started to fight. Several Japanese workers came to the aid of the instructor, as a result of which the worker suffered injuries requiring two days of rest. The about 30 Korean workers that were working in the mine united in demanding that the responsible Japanese individuals be punished. (The workers dispersed with the intervention of the policeman on duty.)

- Sorachi District, Manji Mine (Participants: 68, all of whom were Korean workers)

Dissatisfied with the fact that health insurance premiums and other expenses were being withheld from their pay, workers went on strike demanding wages be raised to 3 yen per day. (The situation was settled with the persuasion of the authorities.)

- Yubari District, Yubari Coalmine (Participants: 238, all of whom were Korean workers)

A cook caught剣春錞 (Geom Chun-sun) stealing a piece of salted fish. The cook struck the worker and delivered him into the hands of Dormitory Master Kiyoshi Kato, who also struck the worker an additional three or four times. Witnessing the beating, the 238 Korean workers demanded that the dormitory master be replaced and refused to enter the mines. (The situation was settled by the chief of the authorities.)

- Yubari District, Yubari Coalmine (Participants: 28, all of whom were Korean workers)

A Japanese named Yojiro Ando assaulted a Korean mineworker named金正 (Kim Jeong-nam) and two others inside the mine. Upon hearing of this, 28 other Korean workers charged toward Ando, but Ando was able to escape. The Korean workers then declared that they would not go to work until the incident had been properly settled and began to leave the mine. At the mine exit, the Korean workers clashed with company employees and threatened action. (The situation was settled by the authorities. Ando was arrested for assault and battery.)

- Hokkaido Colliery & Steamship Company Horonai Mines, Manji Mine (Participants: 47 out of a total of 108 Korean workers)

An immigrant Korean worker named 金教永 (Kim Gyo-yeong) and three others overturned their cart inside the mineshaft and sought the advice of Japanese workers on how to fix the problem. A misunderstanding resulted due to the language problem and the Koreans were angered that they had been treated insultingly. Thereupon, they left the mine and gave exaggerated reports to co-workers saying, “We were just now attacked with a steel bar by a Japanese worker in the mines, and he took away our lamps. We ran out because it was very dangerous. We can’t work in the mines because conditions in the mines are too dangerous.” Due to their agitation, the Korean workers united in their refusal to enter the mine. (The situation was settled with the persuasion of the authorities.)

- Monbetsu District, Sumitomo Kita-Nihon Mining, Konomai Mine (Participants: 280, all of whom were Korean workers)

On October 7, while working in the mine, an argument broke out over a trivial matter between a Korean worker named 盂享

(U Hyang-seop) and a Japanese worker named Masao Kodama. In the course of the argument, Kodama struck and injured U using a steel bar. Thereupon, 45 Korean workers who were in the mineshaft at the time came to the assistance of U and sought to assault Kodama. With the help of some Japanese workers, Kodama was able to escape harm.

On the following day, October 8, 140 Korean workers declared that they were going on strike unless the following demands were met: (1) mend torn futon and bedding by December without charge to the workers, (2) make improvements in food, (3) install accident-prevention equipment and facilities, (4) continue to heat bathwater until 4 p.m. and add a second bath. These workers called on the remaining 140 Korean workers to join them. The united group of 280 workers then went to the company and called for their demands to be met. (Kodama was charged with assault and battery. Stern warnings were issued to the twelve leaders of the Korean workers. With the intermediation of the authorities, the workers’ demands were met.)

- Yoichi District, Tanaka Mining Company, Todoroki Mine (Participants: 30, all of whom were Korean workers)

On December 4, a Korean worker named 甲万于(Gap Man-u) died an unnatural death in the snow. Thereupon, 30 Korean workers united in making the following demands and went on strike. “When there is an unnatural death, the Korean custom is to burn his house and render it unlivable. Therefore, we demand that our dormitory be changed. For the same reason, we demand that our place of work be changed.” (The company accepted the demands on the intermediation of the authorities.)

- Sorachi District, Manji Mine, Miruto Mineshaft (Participants: 68, all of whom were Korean workers)

On December 1, a gas explosion occurred in the mineshaft, killing four Korean workers. A worker named 金米岩 (Kim Mi-am) and three others greatly exaggerated the danger of working in the mine and called for a strike. They also agitated for other disruptive actions, such as work stoppages and filing requests en masse for transfer.

When family members came to Hokkaido to recover the bodies, 鄭渕* (Jeong Yeon-xx) and three others assumed a threatening attitude toward the company and made the following demands. “The company sent them into a dangerous workplace, and therefore the company is responsible for their deaths. We will not take the bodies even if paid compensation of several hundred times. But if there is no choice, we will take the bodies if we are paid ten to twenty times the amount stipulated in the rules.” (The situation was settled with the persuasion of the authorities. 鄭 (Jeong) was questioned on charges of intimidation.)

- Yubari District, Yubari Mines, Heiwa Mine, Kyowa Dormitory (Participants: 256, all of whom were Korean workers)

A fight broke out between two Korean workers at the Kyowa Dormitory. One was 金錫種 (Kim Seok-jong) from North Jeolla Province, and the other was 金徳竜 (Kim Deok-ryong) from South Gyeongsang Province. Acting under the misunderstanding that their compatriot from North Jeolla Province was being mistreated, 56 workers from North Jeolla Province living in the No. 1 Kyowa Dormitory of the Heiwa Mine came to the assistance of金錫種(Kim Seok-jong). Armed with clubs, they sought revenge and attacked the Kyowa Dormitory. (The workers backed down through the mediation of the authorities.)

- Yubari District, Yubari Mining Company (Participants: 238, all of whom were Korean workers)

On December 11, workers said they would not go to work on account of a strong blizzard. Responding to the persuasion of managers, 238 agreed to go to work. However, 40 workers feigned illness and refused to go. Although the blizzard had died down by the following day, December 12, these workers continued to refuse to work. (The situation was settled through the persuasion of the authorities. Stern warnings were issued to the twelve leaders.)

- Yubari District, Yubari Mining Company (Participants: 118, all of whom were Korean workers)

A fight broke out between a Korean miner named 金判同 (Kim Pan-dong) and a Japanese worker named Tsuyoshi Nakagawa on a work-related matter, and Geum Pan Dong sustained a head injury requiring ten days to heal. Following this incident, Korean workers declared it was unsafe to work alongside Japanese workers and went on strike demanding that work teams be formed consisting of only Korean workers. (The situation was settled through the persuasion of the company and the authorities. Tsuyoshi Nakagawa was arrested for assault and battery.)

The Table of Disputes was compiled by the editors of the Special Police Gazette based on reports received from police officers. Coalmining is the quintessential form of “three D labor” (difficult, dirty, dangerous). The entries in the Table of Disputes shows how some Korean workers reacted to these conditions and became embroiled in quarrels and physical exchanges with Japanese workers. It can also be seen that the workers sometimes organized themselves into groups to protest their conditions. However, what is particularly interesting to note from the above 15 cases is that disputes did not arise only from harsh work conditions. Disputes arising from nationalistic sentiments and cultural friction were not rare.

Many of the mineworkers were young workers from the agricultural villages of southern Korea. Most had never come into contact with a different culture before coming to Japan. The young workers probably approached these cultural differences not with a sense of curiosity but with a sense of dread and distrust. From their perspective, what they saw in Japan frequently seemed to be strange, threatening or odd. Take for example the Japanese custom of holding the rice bowl in the left hand and eating with chopsticks. From the Korean perspective, this was the eating style of beggars. What was customary for Koreans was to leave plates and bowls on the table. What would happen if the Japanese were forcing the Koreans to adopt this “style of beggars” as the correct and only acceptable manner for eating? That would certainly incite national and ethnic awareness. In this environment, a dispute could have occurred at any moment.

Can this environment be described as “hell” or “ethnic discrimination” as referred to in Sections I and II above? The following lessons can be derived from the 15 cases cited above. First, in addition to work conditions, disputes were triggered by differences in culture between Koreans and Japanese and by nationalistic and ethnic sentiments. Additionally, some disputes occurred among Koreans due to differences in place of origin and treatment.

Secondly, while animosity and enmity occasionally existed between Korean and Japanese, it should be noted that these workers were toiling alongside each other. If the prevailing working conditions are to be criticized for being “intolerable,” then it should at least be remembered that the Japanese miners shared the same conditions. Work inside the mines was normally carried out by teams of five or ten workers that combined both Japanese and Korean workers.

Seen from this perspective, the scenes of “hell” and “ethnic discrimination” described in Sections I and II can be better understood as the product of the pride of the Korean people living in today’s world. In this context, it can be seen how the “demonic nature” of the Japanese is grossly exaggerated as is the picture of “pure and innocent” Koreans as “victims.” Moreover, the imagination and creativity of Koreans has, almost without exception, been supported by the Japanese people through the provision of historical documents and on a moral basis. An article appearing in Tokyo Shimbun describes Han Soosan, the author of the novel Gunkan-jima (Oyaku Sakuhin-sha, 2009) set in Hashima, in the following manner.

- Interview with Han Soosan, Author of the Novel Gunkan-jima

The author explains that the inspiration for his novel came from Genbaku no zu: dai 14 bu, karasu [The Hiroshima Panels: No. 14, Crows], a panel drawn by the husband and wife team of Iri and Toshiko Maruki picturing the city of Nagasaki after the atomic bomb. The panel measuring 180 cm in height and 720 cm across is covered with crows. Over the bodies of the fallen drifts the traditional Korean costume of the chima and jeogori.

“I was shocked when I first saw the Hiroshima Panels at the Maruki Museum in 1991. Karasu [Crows], the original title of my book, comes from this picture. Mr. and Mrs. Maruki are artists, so painting was their medium of choice. As a writer, my choice was to write a novel. I wanted to go beyond repeating that the atomic bomb is evil. I wanted to express what it meant to be human.”

Gunkan-jima not only describes the conditions after the atomic bomb was dropped. It also graphically portrays how young people were gathered and brought to Japan under the aegis of “conscription” in what effectively was a form of forced labor. The novel describes the cruel passage to Japan and their suffering in the coalmines under terrible working conditions.

“I studied Genbaku to chosen-jin: dai 1 shu ~ dai 6 shu [Atomic bomb and the Koreans: No. 1 ~ 6 collections] compiled by the late Masaharu Oka, a pastor who lived in Nagasaki, and other materials compiled in both Japan and Korea. I also spoke with Mr. Oka and Koreans who had worked in the mines on Gunkan-jima and survived the atomic bomb.”

Among others, the writer Eidai Hayashi has left many volumes on the experiences of Korean miners as “atomic bomb victims.”

- Eidai Hayashi, Chikuho, gunkan-jima – chosen-jin kyosei renko, sono go [Chikuho, gunkan-jima–Korean forced labor and thereafter]

The number of workers in the Hashima coalmines continued to increase with the expansion of mining operations and peaked at about 5,300 in 1945. At this point, people were nearly spilling off the island.

This level of extreme population density with people living on top of each other has a subtle effect on the mentality of residents. This was a life trapped between the sea and the sky with no land to be seen. It was very special environment defined by the extreme rigors of labor that was forced upon the miners. Without a blade of grass to solace the eye, this must have been a scene of death and extinction for its residents.

The buildings on the island first began as three- and four-story wooden structures. But before long, they were replaced by ferro-concrete apartments that soared to heights of eight and nine stories above ground. Tall buildings crammed together with hardly any room to breathe meant that the lowest floors saw little or no sunlight. The days were as dark as night in these lowest reaches. It was as though the miners and their families had been condemned to living at the base of a deep canyon. Needless to say, these lowest floors accommodated the Korean miners and those Koreans who had brought their families with them.

In comparison, the higher floors enjoyed longer hours of sunlight. The view was breathtaking and living conditions were markedly better. The elite members of the Hashima mines occupied this veritable paradise. The Hashima apartments were strictly allotted according to status and occupation.

As a community bound together by a common destiny, a strong sense of solidarity developed among the Japanese workers. At the same time, this sense of solidarity led to intensified discrimination against Koreans and Chinese.

Japanese miners comprised the core workforce in the Hashima coalmines, but large numbers of Koreans had begun to arrive as early as the Taisho Era [1912-1926]. During the war years, the number of Koreans brought here as forced labor grew to about 500–600 miners, including those accommodated in the Yoshida Dormitory. In addition, there were about 80 Koreans who had come here on their own free will with their families. (pp. 158, 163)

There is very little written evidence of any sense of community or camaraderie that may have developed between Japanese and Korean miners in Hashima.

- Hisazo Iwashita, Ashi ga arunoka [Are you sure you aren’t a ghost] (Sumi no hikari [Light of coal], No. 125, June 1955 or 60)

Looking back on my long years of work in the coalmines, I am reminded of so many harrowing scenes… This particular experience takes me back to October of 1936.

In those days, the first shift entered the mine at 6 a.m. Our first task that day was to transport materials to a working face in the mine. The shaft sloped downward to the right and targeted a six-sided vein measuring 12 shaku [3.6 meters]. It was only moments after we had started drilling when the central portion of the ceiling collapsed and slag and water from an older cut rushed in.

The flow was so fast that the small passage that led to the conveyor shaft was immediately plugged, robbing us of our single escape route.

There we were, three of us trapped like mice in a gunny bag. I was then 27 years old and assigned to the working face. The two others were Korean miners: one named 張里 (Jang Ri) (assigned to the working face with rank of gocho sakiyama, or “corporal foreman”), and the other named 白淳 (Baek Sun).

Water continued to flow in, mercilessly adding to the pile of slag that plugged the exit. Rushing by our feet, the water began to climb inexorably.

The space around us was quickly narrowing. “This is how it ends,” I told myself as I resigned myself to my fate. Baek was screaming and sobbing loudly, and his uncontrolled behavior made things only worse.

But unexpectedly (and saved by heaven), the flow of water slowed and the water level began to drop.

“Yes, we can survive this!” I was beginning to feel confident and Jang was doing everything to encourage everyone. We decided we would try to stop the inflow of slag. The three of us worked together with our lives in the balance. We could not have been more serious or more desperate.

This was no easy task. The temperature was rising in the blocked shaft, and to make matters worse gas was beginning to build up. Fresh air was sputtering in fitfully from the air pipe, and the three of us congregated around it with open mouths. The pumps would stop sending air at 11 a.m. That was the rule in those days...

Air pressure started to drop precipitously. “It’s already 10:30,” I thought. Then suddenly the air began to flow with full force. Instinctively I knew a rescue party was approaching. To signal to our rescuers, all three of us continued to bang on the shaft frame.

After struggling for four and a half hours, all of us we were safely rescued. The manager of the mine and many others had anxiously congregated, and they greeted us as we reached safety. We were overwhelmed. A doctor and nurse where on hand, but we were able to exit the mine on our own strength. “Are you sure you aren’t a ghost?” These were the first words that greeted us in the open.