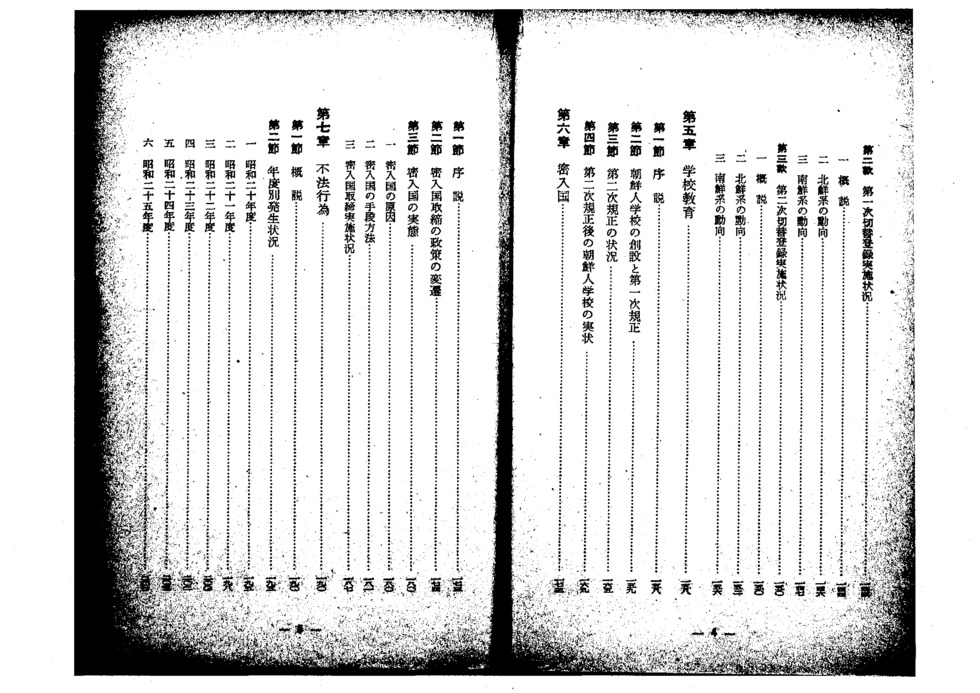

Page 1

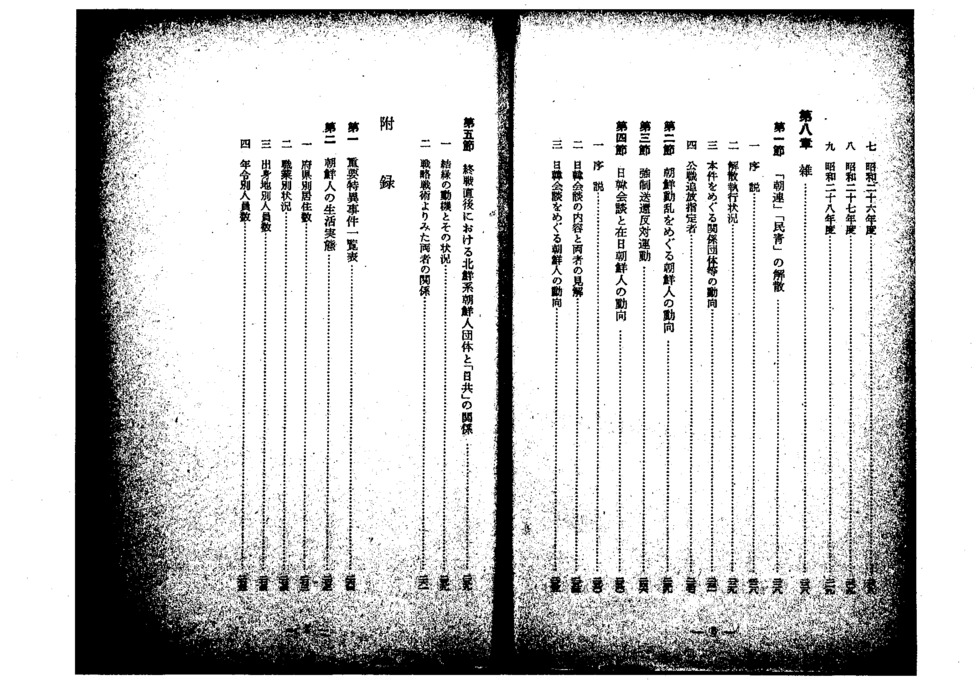

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

Heiji Shinozaki, Zai-Nichi Chosenjin Undo [The Korean Movement in Japan]

(Tokyo, Nagano: Reibunsha, 1955)

[Pp 29-46]

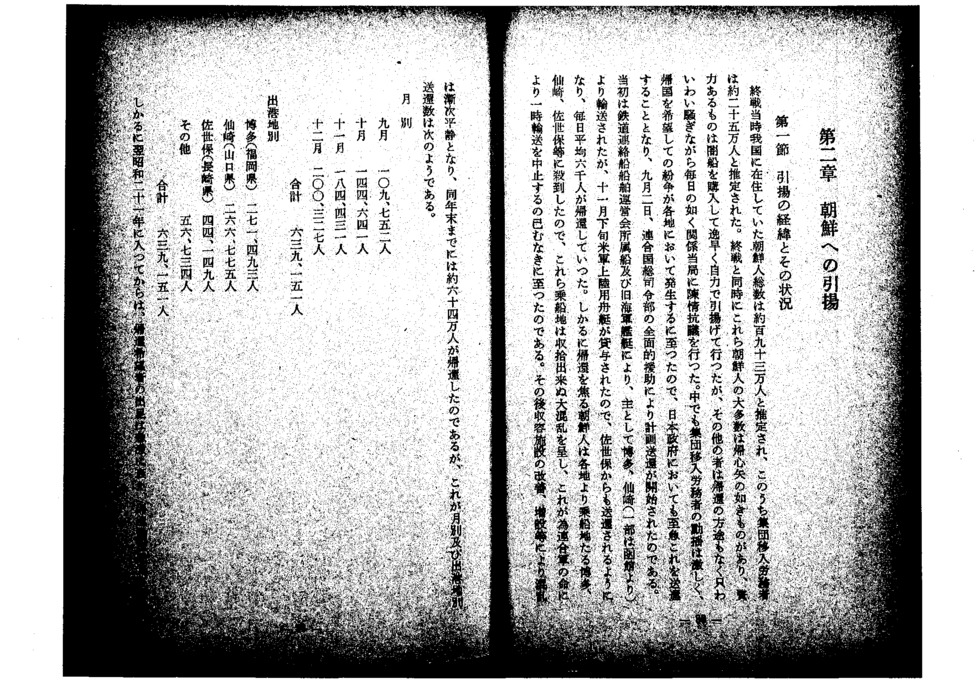

Chapter II Repatriation to Korea

- Background and status of repatriation

At the end of the war, approximately 1.93 million Koreans were estimated to have been living in Japan, of whom around 250,000 were thought to have been conscripted laborers. As soon as the war was over, the majority of the Koreans in Japan were eager to return home. Those with funds bought boats on the black market and quickly made their own way home. Others, however, had no means of returning home and simply continued to petition the relevant authorities even as they bemoaned their own plight. Unrest among the conscripted laborers was particularly intense, and when they started to cause trouble in various parts of the country in their wish to go home, the Japanese government too was moved to repatriate them as soon as possible. A repatriation program was launched on September 2 with the full support of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP). Initially, the returnees were transported primarily from Hakata and Senzaki (as well as some from Hakodate) in boats belonging to the Railway Ship Operating Committee and in former Japanese Navy ships. Then, in late November, the loan of US Forces’ landing craft saw laborers also sent home from Sasebo, with an average of 6,000 departing every day. However, as Koreans impatient to go home flocked to Hakata, Senzaki, Sasebo and other ports, these embarkation points descended into uncontrollable havoc, so that transportation had to be temporarily suspended under order of the Allied Powers. The subsequent expansion and improvement of reception facilities saw the turmoil gradually subside, and by the end of the year around 640,000 Koreans had been repatriated. The breakdown by month and by port was as follows:

By month:

September 109,752 people

October 144,641

November 184,431

December 200,327

Total 639,151

By port of departure:

Hakata (Fukuoka Prefecture) 271,493 people

Senzaki (Yamaguchi Prefecture) 266,775

Sasebo (Nagasaki Prefecture) 44,149

Other 56,734

Total 639,151

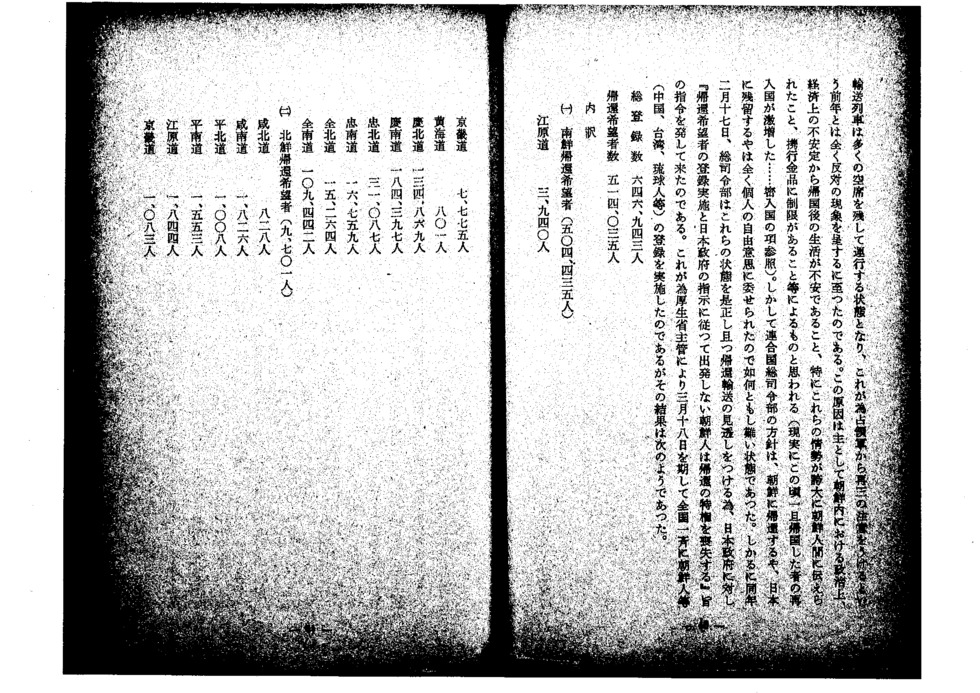

However, in 1946, the number of Koreans wishing to return home rapidly dwindled and transport ships for repatriation and temporary transport trains were running well under capacity. This was completely the opposite situation from the previous year, when the government had been repeatedly warned by the Occupation authorities. The main reasons for the slowdown were concern about life back in Korea given the political and economic instability there, particularly because the difficulties were communicated among Koreans in an exaggerated form, and also the restrictions placed on how much money and property they could take home with them (in fact, there was a surge in repatriated Koreans returning to Japan around that time; see the section on illegal entry). Moreover, SCAP policy was that whether an individual returned home or remained in Japan should be left entirely up to the person, making for a rather difficult situation. However, on February 17, 1946, to redress this situation and make the repatriation process more transparent, SCAP ordered the Japanese government to register the names of those wishing to go home, with Koreans who did not depart according to Japanese government instructions to lose their right to repatriation. The head of the Ministry of Health and Welfare consequently initiated registration of all Koreans and others (those from China, Taiwan, and the Ryukyus, etc.) on March 18, with the following results.

Total number of persons registered: 646,943

Total number of persons wishing to be repatriated: 514,035

Breakdown

(1) Persons wishing to be repatriated to South Korea (504,435)

Gangwon Province 3,940

Gyeonggi Province 7,775

Hwanghae Province 801

North Gyeongsang Province 134,869

South Gyeongsang Province 184,397

North Chungcheong Province 31,087

South Chungcheong Province 16,759

North Jeolla Province 15,264

South Jeolla Province 109,442

(2) Persons wishing to be repatriated to North Korea (9,701)

North Hamgyong Province 828

South Hamgyong Province 1,826

North Pyongan Province 1,008

South Pyongan Province 1,553

Kangwon Province 1,844

Gyeonggi Province 1,083

Hwanghae Province 1,559

Based on these figures, SCAP had also instructed that starting from the last day of April, 4,000 Koreans should be sent home per day according to Japanese government plans, with the repatriation to be completed on September 15. Local government authorities accordingly encouraged repatriation by instructing local Koreans wanting to go home to depart on a stipulated date. However, the repatriation situation remained unsatisfactory, prompting only an increase in the number of Koreans losing their right to repatriation because they had not returned home on the date stipulated. Around that time, repatriation was also suspended three times because of a cholera outbreak, floods, and a rail strike back in Korea, resulting in the end date being pushed back from September 15 to November 15 and then to December 15. The repatriation program was eventually discontinued on December 15 without any improvement in the poor take-up, with actual number of people repatriated since the introduction of registration standing at around 72,000, and around 470,000 Koreans losing their right to repatriation. As a result, of the approximately 1,930,000 Koreans in Japan at the end of the war, given that around 980,000 had gone home by the end of repatriation program, the number remaining in Japan would have been around 950,000. When registration was conducted on March 18, around 647,000 Koreans appeared on the list, so after subtracting the 72,000 who went home during the repatriation program (up to December 15), around 575,000 must have remained in Japan. However, because there were also many Koreans who found their own way home immediately after the war by means such as black market boats, did not register, or entered Japan illegally, the total number of Koreans in Japan after the war is estimated to have been between 600,000 and 700,000 (there were 621,000 Koreans with alien registration as at the end of December 1947). Even after the end of the repatriation program, those who had been unable to return home during the official period because of sickness or other such circumstances were registered with SCAP and allowed to make their way home individually at a later date. A very small number of Koreans consequently continued to leave from Sasebo, but this was stopped entirely with the outbreak of the Korean War (those who had gathered at Maizuru Port immediately before the Korean War to return to Korea had no choice but to go back to their Japanese homes). Those who lost the right to repatriation were not supposed to be given the opportunity to return home for the meantime, but given the possibility that Koreans wanting to be repatriated might start to cause trouble again, the authorities sought to forestall this by giving municipal offices in cities, towns, and villages lists of individuals who had lost their repatriation rights.

- Goods and money carried by those returning home

A September 22, 1945 SCAP Instruction Note entitled “Control over Exports and Imports of Gold, Silver, Securities and Financial Instruments” ordered the Japanese government to ban the import and export of these items, and Ministry of Finance Ordinance No. 88 was consequently promulgated on October 15, 1945 to prohibit those leaving Japan from taking with them gold and silver, securities, and other financial instruments. However, because this was extremely inconvenient for Koreans, Chinese, and others returning home from Japan, SCAP supplementary instructions were issued on October 12, 1945 that permitted Koreans, Chinese, and others returning home to take with them Japanese currency up to the value of 1,000 yen per person. The Japanese government would collect from the owner any yen currency above that value and provide a receipt, holding the money until further instructions were received from SCAP. Based on those instructions, Ministry of Finance Notification No. 271 was promulgated on November 1 that year, lifting the restrictions and the requirement to report imposed by Ministry of Finance Ordinance No. 88 on Koreans and others who were returning home carrying the equivalent of no more than 1,000 yen in currency.

While the ceiling on the amount of currency which Koreans and others returning home were permitted to take with them was therefore set at 1,000 yen, prices subsequently soared markedly, not only in Japan but also in other countries, to the extent that such a sum was not sufficient to cover people’s immediate needs when they arrived home. This quickly forced the Japanese government to increase the permitted amount. At the same time, the growing frequency of movement of people between Japan and other countries required wide-ranging revisions and additions to instructions issued by SCAP in the immediate postwar period. The Instruction Note “Property Individuals are Authorized to Carry on Entering and Leaving Japan” was issued on January 18, 1949 in response to this need, including the following new measures to be taken in relation to Japanese yen taken home from Japan by individuals returning to Korea or the Ryukyus. While the Japanese yen held by individuals returning home was still confiscated, rather than the Japanese government giving those individuals local currency, a receipt was to be given for a maximum of 100,000 yen per family which could be exchanged for local currency when submitted to the government or military authorities back at home. If the amount of Japanese yen taken from individuals returning home was more than 100,000 yen, the Bank of Japan would give each person a receipt in exchange, and hold the money until further instructions were received from SCAP. Based on those instructions, Cabinet Order No. 199 was promulgated on June 3, 1949 on the export and import of property and goods.

While quite strict restrictions were maintained in relation to currency, those on luggage were gradually relaxed, with the initial limit to what someone could carry increased to 250 pounds, while subsequently it became possible to make an application to the US Eighth Army Military Government to take home via special transport 500 pounds of household property and 4,000 pounds of light machinery and other office equipment (in special cases, an application could be made to SCAP for over 4,000 pounds). However, because extremely few people actually applied, these measures ultimately appear to have had little effect in terms of encouraging repatriation. This subsequent relaxation of restrictions also obviously enabled those who had already returned home to send for their luggage as well.

- Choren and repatriation

The Zai-Nippon Chosenjin Renmei (League of Koreans in Japan; “Choren”) was formed immediately after the war as a self-governing body for Koreans residing in Japan, for purposes such as maintaining civil order among their compatriots and dealing with the repatriation issue. Initially, Choren was very cooperative in Japanese government efforts to repatriate Koreans, coming into its own as a self-governing body in both name and substance in helping those returning home to put their affairs in order, voluntarily deploying Choren members to train stations in Tokyo, Shinagawa, Shimonoseki, Hakata, and Haenosaki, etc., to look after the returnees, and otherwise engaging in a remarkable amount of activity. However, as time went on, it started to go too far, meddling in the Japanese government’s repatriation program and ultimately creating its own plan which it then tried to impose. It also threatened and intimidated those Koreans wanting to go home, preventing them from boarding their stipulated trains, or illegally occupying transport trains and using them to go out in groups to buy food supplies directly from farmers in the countryside (“kaidashi,” literally “going out to buy”). With obstructive behavior of this nature becoming increasingly frequent around Japan, SCAP too could no longer ignore what was happening, and on May 7, 1946 it issued an Instruction Note banning Choren from interfering in any way with the Japanese government’s repatriation efforts. As a result, Choren’s illegal behaviors gradually decreased.

[Pp. 172-219]

Chapter VI Illegal Entry

- Introduction

Illegal entry of persons is not a phenomenon particular to Japan, but rather occurs all over the world. It is also not something that occurred for the first time in the postwar period. However, the scale of the problem in Japan, as well as the fact that it occurred after the war, when Japan was in the process of rebuilding as a nation, lent it much greater significance than in other countries and also a certain singularity. Moreover, the issue was complicated still further by the special circumstance of all the ports from which boats were leaving having previously been under Japanese rule. The main reasons for entering Japan illegally were all very easy to sympathize with—to escape social turbulence at home, for example, or to reunite with family members or to study. Particularly given the special relationship between Japan and the countries in question in the past, Japan had little heart for cracking down on the illegal migrants. At the same time, states in particular cannot afford to be swayed by emotion.

In March 1946, SCAP banned entry into Japan of those without permission from the Supreme Commander with the aim of preventing postwar turmoil and ensuring the complete and smooth execution of Occupation policies, and a crackdown was implemented as of April that year by the Occupation Forces and Japanese police authorities. The postwar crackdown was of course undertaken as part of Occupation policy, but its specific objectives were that (a) the mass return [of Japanese citizens] from foreign parts packed Japan’s limited territory to the full, so any further population influx had to be restricted; (b) many illegal entrants were also engaging brazenly in smuggling, and it was vital to prevent the substantial impact that this would have on the Japanese economy, which was still in the process of reconstruction; and (c) some illegal entrants with subversive ideas were joining up with certain elements in Japan with the aim of bringing about a revolution, and these individuals were seriously impacting civil order by passing on critical information and transporting handguns and other weapons, giving rise to the need to forestall and do away with such activities. Even today with the Peace Treaty in force, these objectives remain essentially the same.

- Evolution of policies cracking down on illegal entry

Prior to the war, the Ministry of Home Affairs was in charge of managing alien entry into and exit from Japan. The Ministry handed the matter as a police institution, pursuant to Ministry of Home Affairs Ordinance No. 6 (“Cases Related to Alien Entry, Exit, Residence, and Deportation”). Postwar, however, these institutions and the related laws and regulations were either scrapped or their enforcement was suspended. (As Koreans were Japanese citizens at the time, they obviously received different treatment.)

When the end of the war made those Koreans residing in Japan a liberated people, many went home through a repatriation program conducted by the Japanese government, partly at the call of SCAP and partly at the wish of the individuals themselves. While the program ended at the end of 1946, political, economic, and social unease at home led many repatriated Koreans to remember what their lives were like in Japan, resulting in a steep rise in those returning to Japan. From the perspective of Occupation administration, SCAP was unable to ignore this, and issued an Instruction Note on March 6, 1946 to the effect that non-Japanese nationals who went back to their home countries could not return to Japan until commerce and public transportation became possible, except with the permission of the Supreme Commander. This was followed by another directive on April 2 noting that non-Japanese nationals who are not part of the Occupation Forces would be able to receive permission to enter Japan temporarily, with individuals without permission from the Supreme Commander being prohibited from entering Japan. Anyone entering Japan in contravention of these principles was deemed to be an illegal entrant and was punished by a military court for infringing a SCAPIN or ordered to leave the country.

While these two Instruction Notes were not directly designed to crack down on illegal entry, the directive subsequently issued on June 12, 1946 entitled “Suppression of Illegal Entry into Japan” was entirely focused on combating illegal entry, and was effectively the first instruction note on the issue. The direct aim was to prevent the cholera that was prevalent in Korea at the time from spreading to Japan, and consequently ordered the Japanese government to monitor, seize and detain ships illegally entering Japanese ports. On July 15, the Japanese government decided at a meeting of Vice-Ministers to crack down on illegal smuggling and illegal entry, and laid out an approach to that end. An October 14 decision by the Vice-Ministers on the handling of illegal entrants clarified the division of work among the Ministries of Home Affairs, Welfare, and Transport in relation to the crackdown. As a result, the Ministry of Home Affairs took on arrests, escort of illegal entrants, and guarding of detention facilities; the Ministry of Welfare was responsible for managing and maintaining those detention facilities; and the Ministry of Transport handled the task of repatriation by ship. Smuggling watch-posts were set up under police administration in the prefectures with the most illegal migrants: Yamaguchi, Fukuoka, Saga, Nagasaki, Tottori, and Shimane. A directive again entitled “Suppression of Illegal Entry into Japan” was issued on December 10, instructing the Japanese government to continue with its active campaign against illegal entry, leading to the further bolstering of coast patrols by the police.

Within the Japanese government, because the April 2 directive had suggested that the Japanese government register foreigners who were entering Japan with the permission of the Supreme Commander, as well as formulate a domestic law in relation to crackdowns on illegal entry, the Ministry of Home Affairs led consultations among the relevant ministries that led over a year to the drafting of a plan. Following a Cabinet decision dated April 28, 1947 and Imperial Edict No. 207 issued on May 2, 1947, an Alien Registration Order was promulgated. Article 3 of the Order forbad foreigners from entering the country for the meantime except as permitted by the Supreme Commander, essentially prohibiting the entry of ordinary foreigners into Japan. Persons entering the country in contravention of the Order could be imprisoned for up to six months, fined up to 1,000 yen, or deported. Koreans and Taiwanese, who were not Japanese and whose status had been ambiguous since the end of the war, were deemed to be foreigners for the meantime under Article 11 of the Order, so they too now had to register as aliens.

Implementation of the Order meant that management of entry into and exit from Japan by foreigners was governed by both the April 2 directive and the Alien Registration Order, which strengthened the crackdown on illegal migration even further. SCAP too issued two notes—one on July 8 that year, and the other on December 23—directing specific measures to be taken, which were subsequently implemented by the Japanese government with the cooperation of local Occupation Forces.

On May 1, 1948, the Maritime Safety Board was established to handle illegal activities at sea, but when illegal migration did not decline but rather increased and grew worse, on May 19, 1949, the government issued a Council of Vice-Ministers’ decision on crackdowns on illegal migrants which stressed close partnership among the relevant ministries as well as greater efficiency in order to do everything possible to halt illegal migration.

On June 22, 1949, SCAP issued a directive entitled “Establishment of Immigration Service,” directing that as of November 1 that year, the Japanese government should shoulder responsibility for preventing illegal entry by individuals. A further note entitled “Suppression of Illegal Entry into Japan” and dated November 3, 1949 again stressed the responsibility of the Japanese government for preventing illegal entry, with both SCAP directives and Japanese legal orders directing that these crackdowns should be strictly enforced.

Based on the above directives, the government promulgated Order No. 299 (“Order on Immigration Control”) on August 10, 1949, setting up a new Immigration Division within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Administration Bureau to manage immigration in a rational way, and to liaise with and coordinate among the relevant administrative institutions in relation to the repatriation of illegal entrants. Those institutions included the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the National Rural Police, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Transport, the Maritime Safety Board, and the Ministry of Welfare, with the administrative duties of each laid out in the Order. However, the government was painfully aware that this was not enough to ensure the complete execution of immigration control duties.

On February 20, 1950, SCAP issued a directive entitled “Customs, Immigration and Quarantine Operations,” instructing the Japanese government to review existing customs, immigration, and quarantine implementation methods and establish effective controls consistent with general international practice. However, when the Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950, there were soon indications of a surge in the number of illegal entrants from Korea, creating pressure for the government to establish a single institution as soon as possible. On September 15, a directive on immigration was issued, noting that there were still weak points in the government institutions originally involved in cracking down on illegal entry. It instructed that policies be instituted in relation not only to managing immigration in a rational way, but also to those items concerned with cracking down on illegal entry, and that an institution be established to implement and actively coordinate immigration control. Based on that directive, the Japanese government promulgated Order No. 295 (“Order on the Establishment of an Immigration Control Agency”) on September 30 to bring all those duties under the charge of one organization. The new Immigration Control Agency was set up as an external bureau of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and spearheaded by the above-mentioned Immigration Division.

In response to this move, SCAP noted that while it was good to see a new institution established independently of penal corrective institutions and police organizations, procedures for the deportation of illegal entrants continued to be grounded in judicial procedures, which was out of line with general international practice, so new procedural legislation should be formulated. The government accordingly formulated and promulgated the “Order on Procedures for the Deportation of Illegal Entrants, Etc.” on February 28, 1951 pursuant to a Potsdam Cabinet Order. Subsequently, before the key portions of the Order could be implemented, an American advisor who happened to have been invited to Japan by SCAP to provide guidance on this issue recommended that because of the many difficulties that implementing the Order would entail, and with the Peace Treaty soon to enter into force, a comprehensive order should be formulated that covered not only deportation procedures but also immigration control as a whole.

In line with that direction, the government therefore promulgated Order No. 319 (“Immigration Control Order”) on October 4, 1951 to cover immigration control as a whole, with the Order to enter into force on November 1 that year. At the same time, the “Order on the Establishment of an Immigration Control Agency” (which was required to carry out the provisions of Order No. 319) was also amended to realize the development of legislation and an institution consistent with international practice pursuant to the SCAP directive. With authority over alien immigration control simultaneously handed over entirely to the Japanese government, Japan regained autonomy over immigration control seven years after the end of the war. Because of the circumstances, it was decided that the Alien Registration Order would remain as the means of controlling illegal entry by Koreans and Taiwanese for the meantime. However, as the entry into force of the Peace Treaty would officially remove their Japanese citizenship and make them legally foreigners, creating an irrational situation whereby there were two different laws for alien immigration control, the government began revising the law. It formulated and promulgated the Alien Registration Law on April 28, 1952 as Law No. 125 so that all alien immigration control could be carried out under the Immigration Control Order. (Obviously, with the entry into force of the Peace Treaty, Koreans and Taiwanese resident in Japan became aliens in both name and substance, so their entry into and exit from Japan became entirely subject to application of the Immigration Control Order.) Law No. 126: Disposition of Ministry of Foreign Affairs-Related Orders based on Orders Issued in Consequence of Acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration, which was issued the same day, made the Immigration Control Order legally binding.

On August 1, 1952, reform of administrative institutions saw the Immigration Control Agency become an internal bureau of the Ministry of Justice, and its name was changed to the Ministry of Justice Immigration Bureau. The organization previously had been an external bureau of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. However, its duties remained the same.

- Actual status of illegal entry

(a) Causes of illegal entry

After the war, Japan made steady progress under the management of the Occupation Forces toward rebuilding itself as a democratic state, but Korea and other countries which were previously Japanese territory did not necessarily follow the same reform trajectory as Japan. Another factor was the complex entanglement of Communist elements, with the result that major political, philosophical, and economic gaps emerged between these countries and Japan. If these gaps could be called disparities, it is these disparities that inevitably and regularly have been the causes of illegal entry into Japan. Specific causes for illegally entering Japan—from the end of the war until recently—can be broadly divided into escape from social unease, work, study, visiting, living with others, draft avoidance, and smuggling, but in addition, a small number come to Japan with dangerous objectives related to special political assignments.

Obviously, these factors also changed slightly according to the particular circumstances of the time. Escape from social unease stood as by far the most common reason in the first two or three years after the Second World War. The division of Korea into opposing sides on the north and south led to tragic fighting between fellow countrymen, while the policies adopted by the government of South Korea also failed to match the expectations of the people, with the strict enforcement of anti-communist policies by the government giving the strong impression that it was a police state. Deteriorating economic conditions too made most of the public extremely worried about daily life, and many Koreans put themselves on board small boats and left behind the north-south conflict of their homeland to enter Japan illegally and to enjoy the stability of life there.

(b) Means and methods of illegal entry

(i) Boats, etc.

Most of the vessels used for illegal passage to Japan are small steamships (motorized sailboats) of less than 10 tons that carry from about 10 to 20 passengers per voyage. Some boats are above 10 tons up to around 20 tons and carry many more people—up to 100—but these cases are extremely rare. Reasons for the common use of small boats include:

- If they are caught and confiscated, the loss incurred is comparatively small;

- They are comparatively easy to acquire and operate;

- Small boats are comparatively likely to escape official notice; and

- Small boats can dock anywhere along the coastline.

Another characteristic of these small boats is that many are old, which, as noted above, is because of the price issue, as well as the limited loss in the case of confiscation, etc.

A comparatively large number of ship owners are Japanese, but more recently, quite a few Koreans have also begun buying boats or chartering them for single voyages. Crews too tend to be primarily Japanese because of their knowledge of shipping routes around Japan and Japan’s coastal geography, which meant they can skillfully slip across zones that are closely patrolled and arrive more easily at the vessel’s destination.

(ii) Circumstances at the point of departure

The two most common means employed by illegal entrants of securing passage by boat are through mediation by an illegal boat broker, or by acquiring a boat together with other people and sailing it to Japan themselves (in other words, self-piloted), of which the former method is by far the most common.

- Brokered voyages

Brokers live in ports such as Busan, Masan, Tonyeong, and Yeosu, which are known to be homes to smuggling bases, and are apparently extremely thorough in keeping up-to-date with the situation in Japan, not only by constantly monitoring the movement of Japanese authorities but also by contacting relatives and acquaintances living in Japan to track the actions of regulatory authorities. They apparently also closely study the coastline of the Kyushu and San-in regions and the status of smuggling watch-posts, etc. When they have gathered the desired number of people wishing to be smuggled into Japan, they boldly and skillfully target weak points in the patrol dragnet with a very high success rate. Some brokers even have their own ships; others do not, in which case the broker usually takes and holds the passage fee, paying it to the ship owner when the voyage succeeds—in other words, when the boat reaches Japanese territory. It is therefore common for ship owners (captains; brokers included) to get to shore, wherever it is, to land the passengers quickly and then immediately escape. Brokers on the Japanese side, who live in Tsushima, Kyushu, and the San-in regions, are in collusion with them and keep closely in touch, making it even easier to smuggle people into the country. While there is a certain amount of variation in the passage fee paid to brokers, it is generally between 15,000 and 30,000 yen and is almost always paid up front. Some brokers also have a large number of illegal registration certificates which they sell to Korean customers for extremely high prices.

- Self-piloted voyages

Those who acquire boats to smuggle themselves into Japan generally have considerable financial resources and the ability to buy a boat; confidence in their sailing and navigation abilities from experience as sailors and fishermen (including cases where the group planning the voyage contains people with such experience), and are familiar with Japan, and particularly the Japanese coast. Reasons for not going through a broker but rather overcoming the considerable difficulties involved in self-piloting a boat include:

- Steep passage fees make it much cheaper to buy an old boat to use;

- In some cases, if the boat can be resold once it reaches its destination, this is even more advantageous; and

- Brokers tend to be interested solely in making money, going through the motions without taking ultimate responsibility for their acts, so some people believe that the success rate is conversely higher with self-piloting.

(c) Landing in Japan

Boats used by smugglers choose a stretch of coast that is comparatively lightly policed, usually land late at night or early in the morning, and then flee immediately. Some also communicate with the shore via torch signals or flares as they approach, guiding the boat into a safe spot. Others have relatives or acquaintances, etc., who live in Japan come to meet the boat, and skillfully reach their destination based on a prearranged plan. In many of these cases, registration certificates have been illegally acquired. For those who do not have such support waiting in Japan, option include waiting in a nearby lodging or private house arranged through the mediation of a broker or other persons to work on acquiring a registration certificate, or to contact acquaintances and other connections for money and other assistance. They apparently also avoid regular public transport such as trains and buses and instead hire a car to get right away and slip into the Hanshin (Osaka-Kobe) region. Because illegal entrants are often crammed into small vessels or packed into the bottom of the boat, they often arrive in very poor condition, and there have been cases where the passengers could not stand the hardship and intimidated the captain into landing despite knowing that they would probably be discovered, and were in fact arrested.

(d) Other

Other methods of entering the country include:

- Boarding fish carriers;

- Landing in Japan by pretending that a ship is in distress;

- Entering Japan as a legitimate crew member of a ship in order to go ashore on a shore pass and then making a run for it;

- Paying a ship’s crew member to smuggle the person/people into Japan in the ship’s hold; or

- Boarding a boat under the protection of a special organization.

However, there are extremely few such cases.

(e) Smuggling routes

There are three main smuggling routes: one from South Korea, one from North Korea, and one following an international shipping route. The South Korean route is the most frequently used.

(i) The South Korean route leaves from Busan, Masan, Tonyeong, Yeosu, Jinhae, or Jeju Island, etc., and from there:

- Goes straight to Kita-Kyushu or the San-in region;

- Stops in at Tsushima or Oki and then goes on to Kita-Kyushu or the San-in region;

- Goes around the southern coast of Kyushu and goes through the Bungo Channel into the Seto Inland Sea; or

- Lands on the Pacific coast of Shikoku from the southern coast of Kyushu, or goes through the Kii Channel to land in Wakayama, Tokushima, Kobe, or Osaka.

The most frequently used routes go to Nagasaki, Yamaguchi, and Fukuoka because they are the shortest routes between Korea and Japan. These areas are the most heavily policed, and reasons for choosing these routes despite the danger include:

- The cheap passage fee;

- A very safe passage; and

- The poor capabilities of the boats used.

(ii) Extremely few people take the North Korean route, but many boats leave North Korea from Wonsan for destinations in the Hokuriku or Hokkaido regions, such as Niigata, Ishikawa, Toyama, Akita, and Hakodate, and these are often used by agents on special missions.

(iii) International shipping routes are primarily used for smuggling goods, so boats land at Miike, Shimonoseki, Kure, Kobe, Yokkaichi, Nagoya, or Yokohama, for example, but the number of such boats is not great.

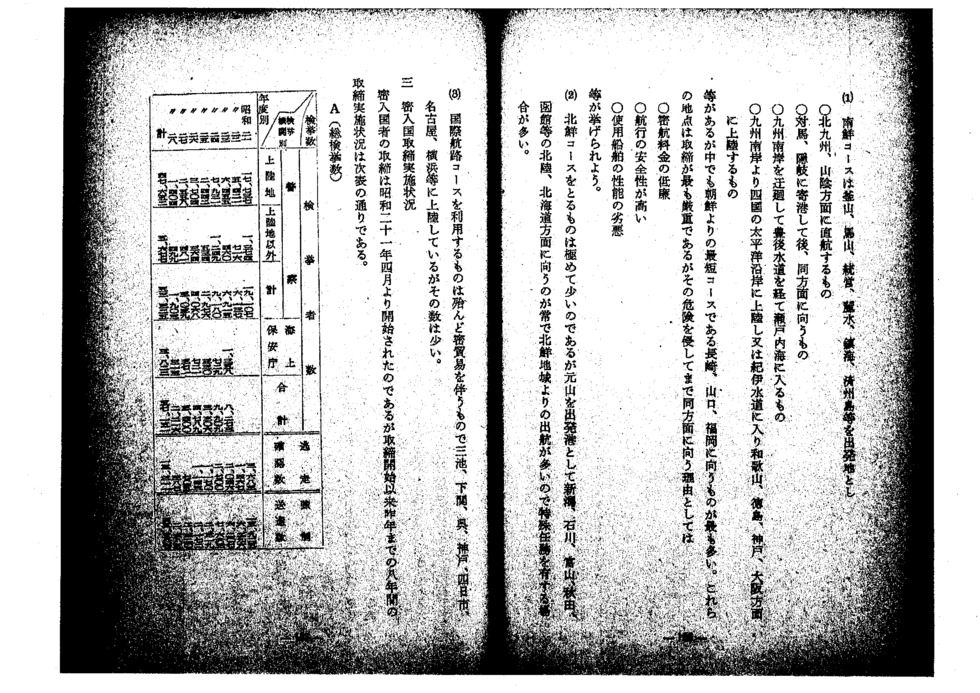

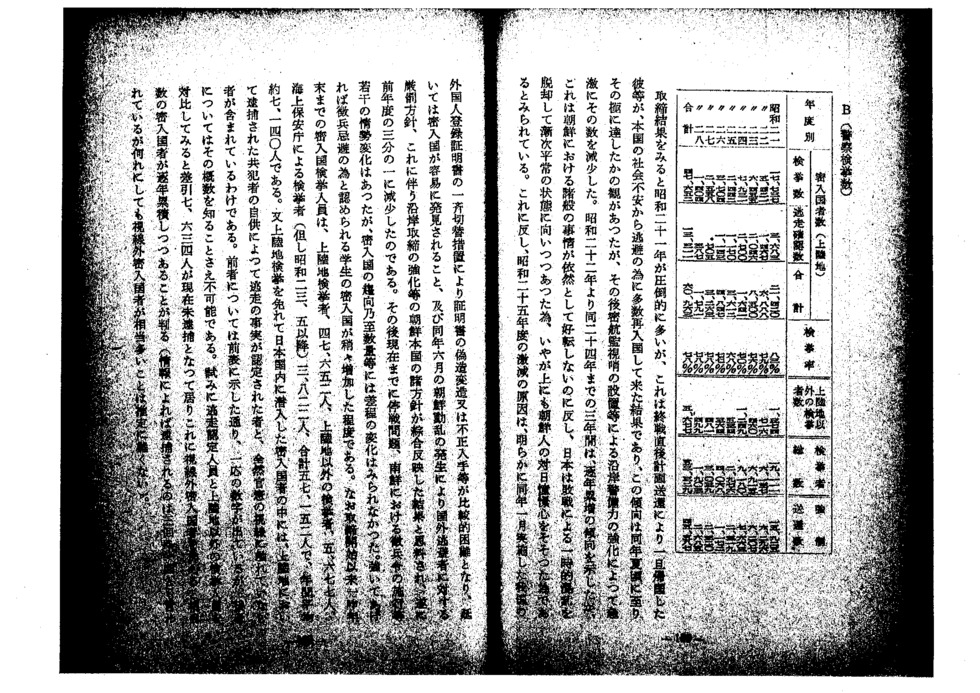

(c) Status of illegal entry crackdowns

The status of illegal entry crackdowns for the eight years between the launch of crackdowns in April 1946 to last year is shown in the table below:

- Total arrests

|

No. of arrests |

No. of persons arrested |

No. of confirmed escapes |

No. of deportations |

||||

|

By arresting organization |

Police |

Maritime Safety Board |

Total |

|

|

||

|

By year |

At point of landing |

Outside point of landing |

Total |

Total |

|

|

|

|

1946 |

17,737 |

1,374 |

19,107 |

|

|

3,683 |

15,925 |

|

1947 |

5,421 |

716 |

6,137 |

|

|

1,467 |

6,296 |

|

1948 |

6,455 |

460 |

6,915 |

1,358 |

8,273 |

2,046 |

6,207 |

|

1949 |

7,931 |

1,249 |

9,180 |

729 |

9,909 |

2,700 |

7,663 |

|

1950 |

2,442 |

534 |

2,976 |

330 |

3,306 |

1,170 |

2,319 |

|

1951 |

3,704 |

364 |

4,068 |

721 |

4,789 |

1,143 |

2,172 |

|

1952 |

2,558 |

481 |

3,039 |

371 |

3,410 |

705 |

2,320 |

|

1953 |

1,404 |

499 |

1,903 |

313 |

2,216 |

387 |

2,685 |

|

Total |

47,652 |

5,677 |

53,325 |

3,822 |

57,151 |

13,311 |

45,587 |

- Police arrests

|

|

No. of illegal entrants (At point of landing, etc.) |

Arrest rate (%) |

No. of arrests other than at point of landing |

Total no. of arrests |

No. of deportations |

||

|

By year |

No. of arrests |

No. of confirmed escapes |

Total |

||||

|

1946 |

17,737 |

3,683 |

21,420 |

83 |

1,374 |

19,111 |

15,925 |

|

1947 |

5,421 |

1,467 |

6,888 |

79 |

716 |

6,137 |

6,296 |

|

1948 |

6,455 |

2,046 |

8,500 |

76 |

460 |

6,915 |

6,207 |

|

1949 |

7,931 |

2,700 |

1,641 |

70 |

1,249 |

9,180 |

7,663 |

|

1950 |

2,442 |

1,170 |

3,612 |

68 |

534 |

2,976 |

2,319 |

|

1951 |

3,704 |

1,143 |

4,847 |

77 |

364 |

4,068 |

2,172 |

|

1952 |

2,558 |

705 |

3,263 |

78 |

481 |

3,039 |

2,320 |

|

1953 |

1,404 |

387 |

1,791 |

78 |

499 |

1,903 |

2,685 |

|

Total |

47,652 |

13,311 |

60,963 |

78 |

5,677 |

53,329 |

45,587 |

While the results indicate that 1946 had by far the largest number of arrests, this was because of the many Koreans who went home as part of the repatriation program immediately after the end of the war but returned to Japan to escape the social unease at home, a trend which appears to have reached its peak around summer that year. With the subsequent strengthening of Japan’s coastal policing capacity, however, including the establishment of smuggling watch-posts, those numbers dropped dramatically. There was still a cumulative increase over the three years from 1947 to 1949, which appears to have been because conditions in Korea remained less than favorable while Japan had broken free of postwar turmoil and was gradually returning to normality, fostering a reluctant admiration and respect for the country among Koreans. The steep drop-off in 1950—with arrests down to almost a third of the previous year—was clearly due to the complete switch to alien registration cards implemented in Japan in January that year, which made it comparatively difficult to create or acquire fake cards, and also made it easy to identify illegal entrants. Korean government policies introduced in response to the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, including stiff punishments for anyone fleeing the country and the concomitant bolstering of coastal policing, were also believed to have an effect. From that time to the present, while there have been some slight changes to the situation, such as the armistice issue and the introduction of a conscription ordinance in South Korea, there have been no major changes in trends or numbers in terms of illegal entry, other than perhaps a small increase in the number of students entering Japan illegally in order to escape the draft back home.

Looking at the number of illegal entrants arrested since the crackdown began to the end of 1953, 47,652 were arrested at the point of landing, 5,677 somewhere else, and 3,822 apprehended by the Maritime Safety Board (since May 1948), making for a total of 57,152, or an average of about 7,140 a year. The number of illegal entrants who evaded arrest and blended into Japanese society includes those whose escape was confirmed through the confessions of accomplices arrested at the point of landing, as well as those who have gone unnoticed by the authorities. While we have the figures noted in the table for the former, it is impossible to even estimate the number of those in the latter category of people who have gone unnoticed. As a rough guide, a comparison of the number of illegal entrants confirmed to have escaped, with those arrested elsewhere than at the point of landing, would suggest that 7,634 people currently continue to evade arrest, and if we add to that those illegal entrants who have escaped the attention of the authorities, it would seem that the number of illegal entrants at large has been going up over time (information suggests that one in every three illegal entrants is arrested, so it is easy to imagine that a considerable number are going unnoticed by the authorities).

Pp 190-227

Chapter VII Illegal Behavior

- Overview

Koreans generally have little cultural education and little respect for the law, while by nature they tend to be power-worshippers who easily follow the crowd. Complex characters, they are emotional and brutal; clever, sly, vain and indulgent; fond of gambling and lacking in the will to work. While on the other hand they also have strong points, the above can be viewed as faults common to the Korean national character. In addition, because many of the Koreans residing in Japan are said to be from a comparatively low social class at home, those faults could be said to be particularly marked, as is clearly evidenced by the high crime rates that emerge in statistics.

Not only do they have this strong inherent criminal bent, but the Choren leaders who were under the control of the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) after the war took every opportunity to stir up wide-ranging political trouble and violence with the aim of turning the masses into a revolutionary force, which exacerbated such tendencies. Their criminal behavior, as well as inappropriate policies adopted by the authorities, aggravated postwar turmoil and caused extreme social unease to the extent that on some occasions, it was as if police were absent.

This may have been the result of complicated national sentiments buried at the bottom of Korean hearts that erupted to the surface after Japan lost the war. As such, it might be no more than a phenomenon particular to a transitional phase, and it would certainly not be right to assume it as typical of the national character as a whole. However, even today, nine years since the end of the war, when conditions in Japan are gradually returning to normal and domestic order is rapidly recovering, the crime rate of Korean people nevertheless remains extremely high compared to Japanese and other foreigners, and whatever this says, it is a reality that both they and we should be deeply concerned about. The emergence of criminal behavior also appears not only to be consistently influenced in a strong way by current discourses in Japan and elsewhere, increasing or dwindling in line with measures taken back in Korea or in Communist states, but it is also undeniably closely linked to the policies of the Japanese government toward Koreans. Illicit behavior by Koreans during eight years of the postwar period can be divided chronologically into the following five phases.

Phase 1: From the end of the war to February1946

After the end of the war, because they regarded themselves as victors, Koreans residing in Japan felt no need to follow the laws of the losing country and engaged brazenly in illegal behavior in various places around Japan, causing disgust among the general public. Their behavior reflected not only their image of themselves as a liberated people, but also the ambiguous attitude of the Occupation Forces toward them and the failure of the Japanese authorities to crack down on their behavior due to the lethargy and loss of confidence brought on by the shock of losing the war. The main types of incidents in Japan were illegal behavior in relation to unfair demands for retirement benefits; clashes between groups of Japanese and Koreans; menacing behavior arising out of the repatriation issue; Choren’s own self-defense organization acting as though it had the same rights as the police; and group kaidashi of staple food. A particularly well-known incident was the Niigata Nippōsha attack.

Phase 2: To September 1949 (dissolution of Choren)

On February 19, 1946, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces issued an instruction on the exercise of criminal jurisdiction that at least clarified the legal grounds for enforcing the law, enabling the authorities to become more proactive about addressing crime, but the above illegal behavior did not decline and instead counterattacks and resistance to police crackdowns continued. In addition, there were also many incidents of fights between groups of Koreans and Japanese, confrontations between Choren and the Korean Residents Union in Japan (Mindan), disruptions of trains for kaidashi purposes (illegal occupation of passenger trains), theft, and large-scale racketeering. A particular feature of this period was the transformation of Choren members into “shock troops” for the JCP, resulting in numerous types of illegal businesses that were organized and radical. This was the period when Choren was at its peak. Key incidents during this phase included the demonstration in front of the Prime Minister’s Residence, the Hanshin education incident, the Masuda incident, the Fukagawa incident, and the Shimonoseki City incident.

Phase 3: To June 1950 (outbreak of the Korean War)

The dissolution of Choren and the Democratic League of Korean Youth in Japan (Minsei) saw a dramatic decrease in illegal behavior by Koreans resident in Japan, but under the direction of the leaders of the former Choren and the JCP, a Defense and Struggle Committee was set up to obstruct the confiscation of former Choren property that was carried out as part of measures taken to disband the group, and there were numerous cases of major counterattacks against the relevant authorities around Japan, as well as protests and fighting, the most representative of which was the Taito Hall incident.

Phase 4: To April 1952 (entry into force of the Peace Treaty)

Immediately after the outbreak of the Korean War on June 25, 1950, North Koreans set up two committees in quick succession to help in the defense of and struggle for their homeland, in hope of a victory by the North Korean army: the Homeland Defense Committee (Kensen) and the United Democratic Front of Koreans in Japan (Minsei). Taking homeland defense as their primary slogan, various anti-American and anti-Occupation gatherings and protests were held frequently across Japan to stir up national feeling, resulting in incidents in which anti-American leaflets were distributed and other incidents in which the production and transportation of military supplies for South Korea were disrupted. In the fall of 1950, these groups allied with the JCP to fight the Red Purge and to protect Koreans’ living rights, initiating various types of illegal behavior simultaneously. In the fall of 1951, when the Migration Control Ordinance was formulated, vigorous opposition broke out against forced repatriation, with waves of protests in in front of the Diet, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Justice, etc., as well as attacks on police headquarters and other institutions of power. Influenced by the resolutions adopted at the 4th and 5th JCP National Conferences in the spring of that year on adopting military action, this illegal behavior included the widespread use of handguns as well as makeshift weapons such as gasoline bombs, acid bombs, and tear gas. There were many famous incidents during this phase, including the second Kobe incident, the Oji incident, the Yamato-cho incident, the Higashinari Police Station attack, the Hino incident, and the Takasago-cho incident.

Phase 5: (To the present)

The entry into force of the Peace Treaty on April 28, 1952 turned Koreans in Japan into foreign nationals. With the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea yet to be signed, for example, there was substantially no change in the situation, so illegal behavior based on the policy of military action adopted by the JCP the previous spring continued unabated, and on May Day (May 1), the biggest riot of the postwar period was instigated in conjunction with the JCP in the public plaza in front of the Imperial Palace, drawing public attention at home and abroad. This was followed by a string of incidents involving large-scale, malicious, and illegal behavior, including the Suita riot in Osaka on June 25 (the anniversary of the Korean War), a clash with police in front of Shinjuku Station, and the July 7 Osu incident in Aichi Prefecture, with civil order deteriorating by the day. However, following the appearance of an essay by JCP politician Kyuichi Tokuda in the party newspaper Akahata on July 5 which criticized such violent street tactics, the rash of illegal behavior began to die down, with fewer organized and planned incidents taking place. Even when the switchover to alien registration cards went through at the end of September, there was almost none of the anticipated illegal behavior but rather only legal protests, with the change going through quite peacefully. The subsequent transition of Korean schools to private status and the resumption of bilateral talks between Japan and South Korea have stirred strong and persistent North Korean opposition, but this has remained within legal bounds without reaching the level of illegal behavior.

Trends in illegal behavior and security offenses by groups of Koreans from the end of the war through to the present were summarized above; the details are described below.

Note: Because of the lack of relevant materials and inconsistent statistical formats, it is sometimes difficult to identify details accurately and systematically in the explanations below, and the author was forced to look at different years from different standpoints.

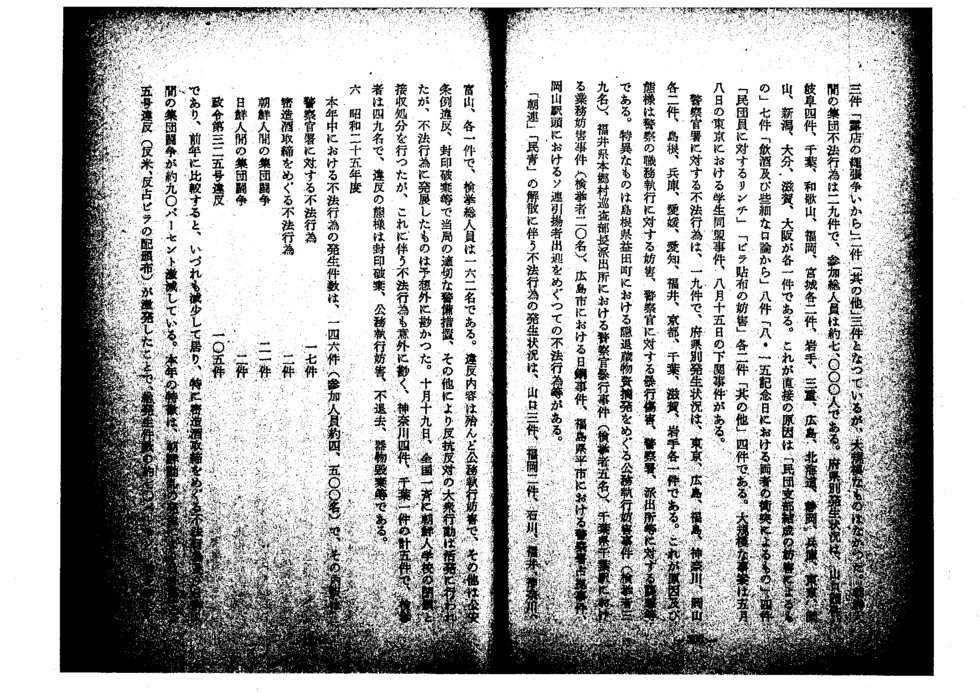

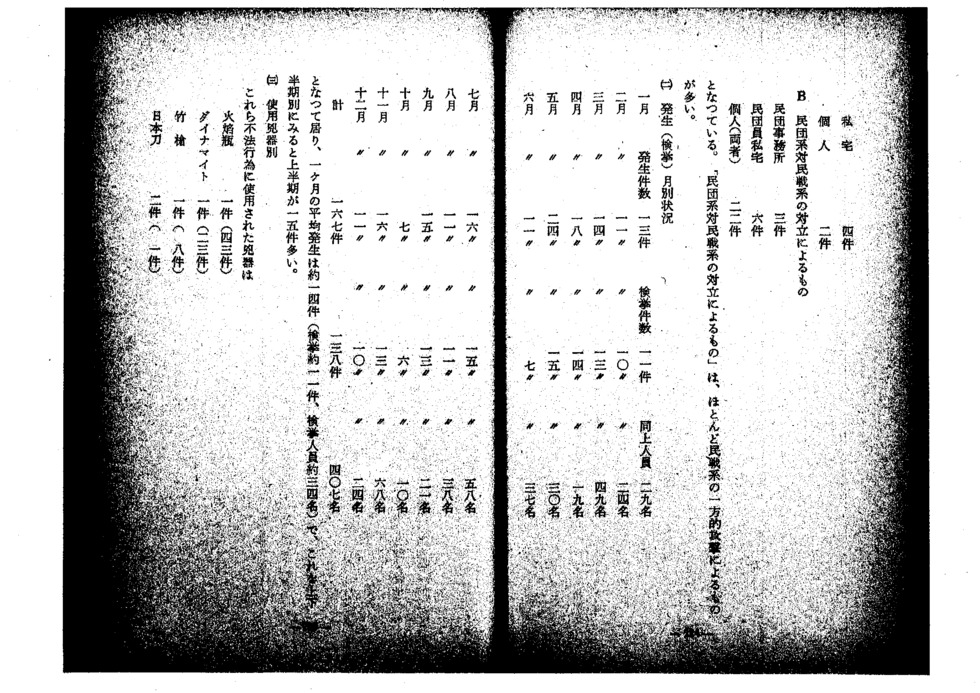

- Overview of incidents occurring by year

(1) Fiscal year 1945 (from the end of the war to the end of 1945)

Among those Koreans resident in Japan at the end of the war were some elements in leadership roles who resented Japan’s former rule and used contemptuous, anti-Japan rhetoric to direct and stir up the masses, saying, for example, that until then, Koreans had been discriminated against, exploited, oppressed, and treated like slaves. Now that the war was over and they had been liberated, they belonged to an Allied nation so they had no obligation to comply with the laws of defeated Japan. The Japanese must be brought to realize by whatever means possible that Koreans were now second-class citizens while the Japanese were fourth-class, and that Koreans should therefore naturally receive better treatment than the Japanese. Sanctions should be imposed on the Japanese as war criminals for the way that they had tortured the Koreans during the war.

At the same time, these elements also formed various types of associations across Japan, cleverly using their fellow countrymen’s struggles with unemployment, making a living, and issues around returning home to bind them together and resolve issues through sheer weight of numbers. This kind of incitement brought forth a backlash as the long-suppressed emotions of ordinary people exploded, leading them to ignore or neglect Japanese laws and regulations and come into conflict with the authorities, with examples of violence abounding. For example, they would intimidate other people so that they could get train tickets first or illegally occupy rail carriages to go on group kaidashi; make unfair demands in government offices or the workplace, and, when these were refused, surround and attack the place; or else their self-appointed defense groups would act well beyond their legal mandate just as if they had the same authority as the police. The police authorities too put a considerable amount of effort into suppressing and preventing the various types of illegal behavior, but it is an undeniable fact that due to various fundamental causes such as social turbulence immediately after the war, restructuring of police organizations, and the lack of clarity about criminal jurisdiction in relation to Koreans, some “gaps” had been created. Over this particular period, 128 cases of illegal behavior occurred, with the monthly breakdown as follows:

August 5

September 19

October 26

November 36

December 42

While the figures did continue to grow every month, a breakdown of the cases was as follows:

Mass assaults on Japanese managers 6

Threatening behavior over the allocation of supplies 8

Fights among multiple persons arising from gambling 5

Fights between groups of Japanese and Koreans 8

Fights between groups of Koreans and Chinese 5

Threatening behavior over repatriation issues 21

Unfair demands over leaving jobs or compensation, etc. 34

Gang theft 8

Illegal and unfair demands on authorities, etc. 14

Self-defense squads acting as if they had police authority 9

Illegal occupation of offices 2

Fights between members of Korean associations 6

Other 2

In other words, types of illegal behavior that had not been anticipated before the end of the war occurred frequently. In terms of the timing, the three months of August, September, and October were dominated by resistance to Japanese managers on the company side in mining areas (i.e., collective working environments); assaults and fights involving groups of Koreans and Chinese arising from emotional confrontations, as well as disputes over gambling; and threatening behavior accompanying unfair demands for pensions, travel expenses, and other costs related to the repatriation issue. From mid-October through to November, there was a surge in threatening behavior, with the string of Korean self-governing bodies that had been formed (around 300, starting with Choren) participating actively in fights at military supply factories and offices over illegal and unfair demands in relation to benefits such as retirement pay, using their power as groups to threaten violence, or refusing to be transported home as part of the repatriation program. In December, in addition to a spike in illegal and unfair demands made on government agencies, there were a whole string of incidents such as the illegal appropriation of the property and offices of Koseikai (an external department of the Japanese government tasked with improving the lives of Koreans), illegal behavior arising from power struggles between Korean associations, and fights between Japanese and Koreans, all involving significant use of handguns, swords and other weapons.

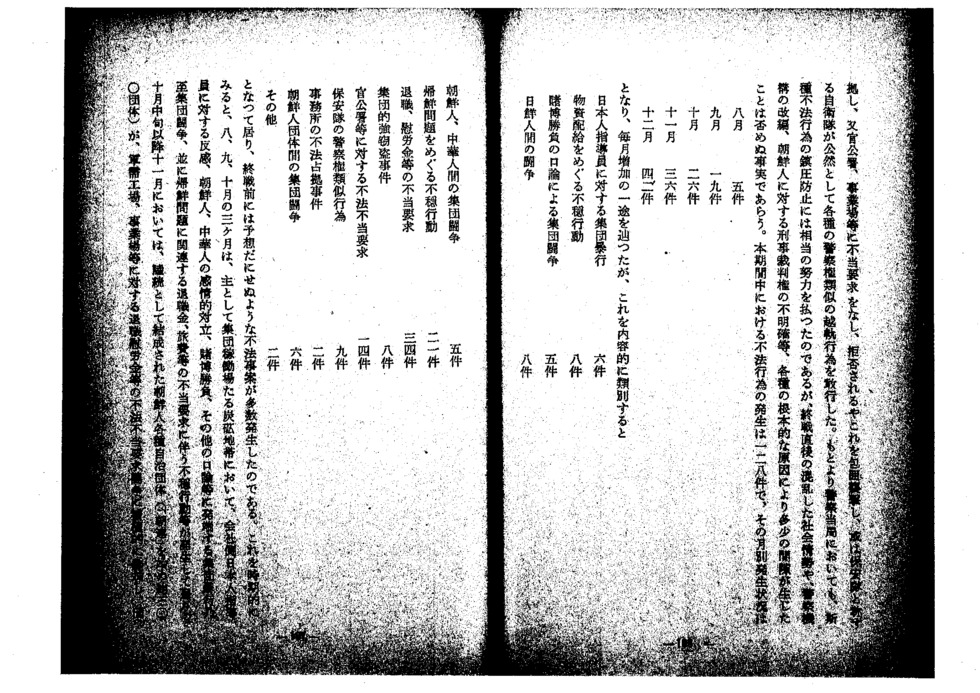

- Fiscal year 1946

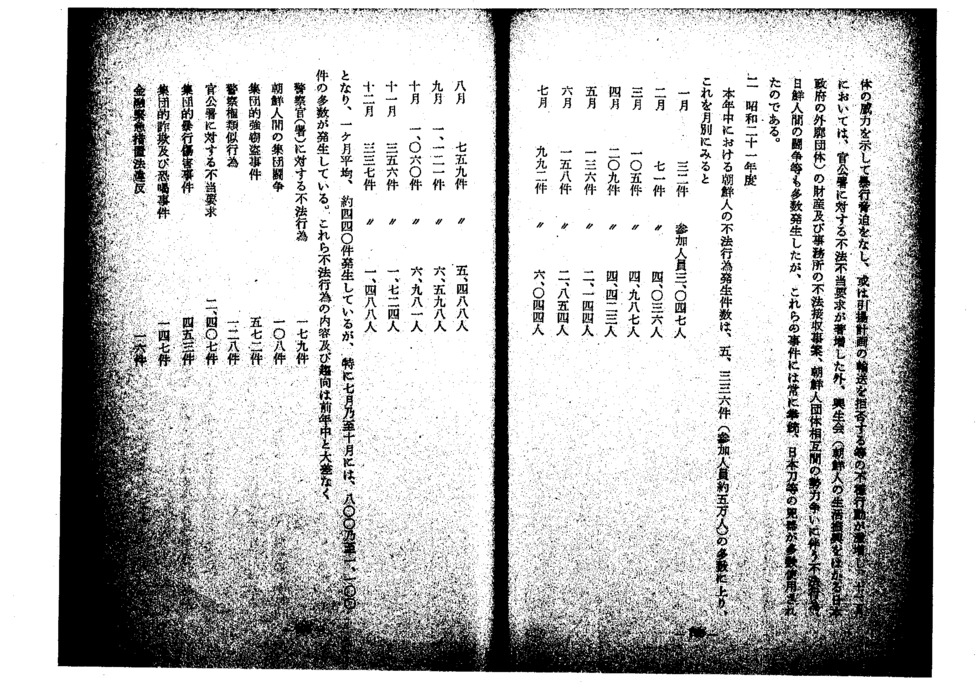

The number of illegal activities involving Koreans rose steeply to 5,336 (involving around 50,000 people), with the monthly breakdown as follows:

January 32 cases 3,047 people involved

February 71 4,036

March 105 4,987

April 209 4,423

May 136 2,144

June 158 2,854

July 992 6,044

August 759 5,488

September 1,121 6,598

October 1,060 6,981

November 356 1,724

December 337 1,488

The monthly average was around 440 cases, with particularly high figures between July and October (800 to 1,100). In terms of types of behavior and trends, there was no great difference from the previous year.

Illegal behavior toward police (stations) 179

Fights among groups of Koreans 108

Gang theft 572

Actions imitating police authority 128

Unfair demands on authorities 2,407

Gang assault and injury 453

Gang fraud and extortion 147

Violations of the Act on Emergency Financial Measures 16

Illegal behavior in relation to rail transport 580

Other 750

Among these, frequent illegal occupation of trains (carriages) for group kaidashi was particularly marked. The best-known incident from 1946 was the demonstration in front of the Prime Minister’s residence on December 20.

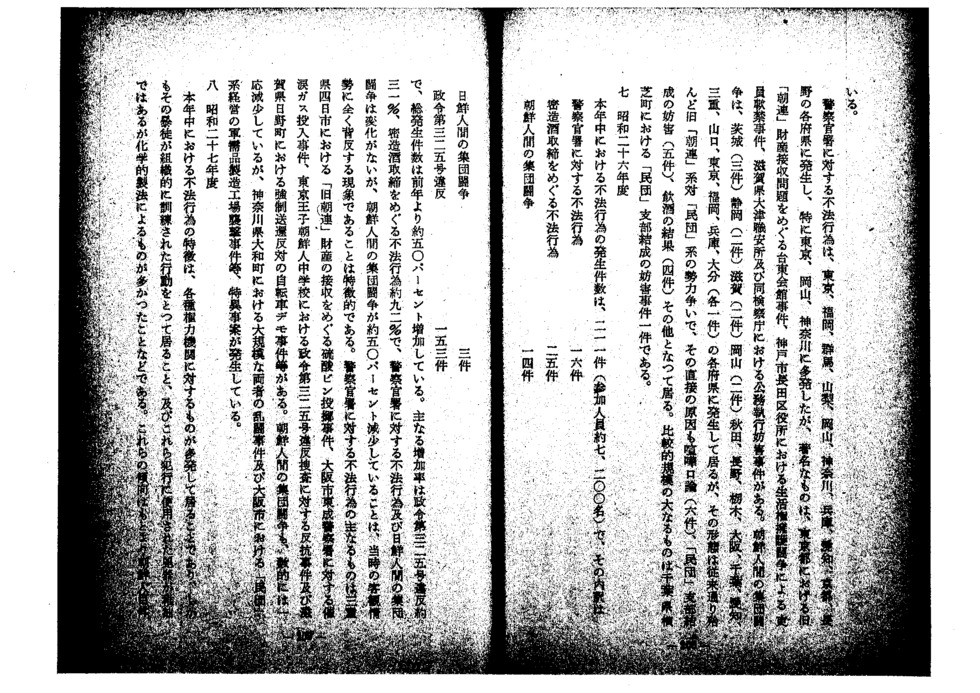

- Fiscal year1947

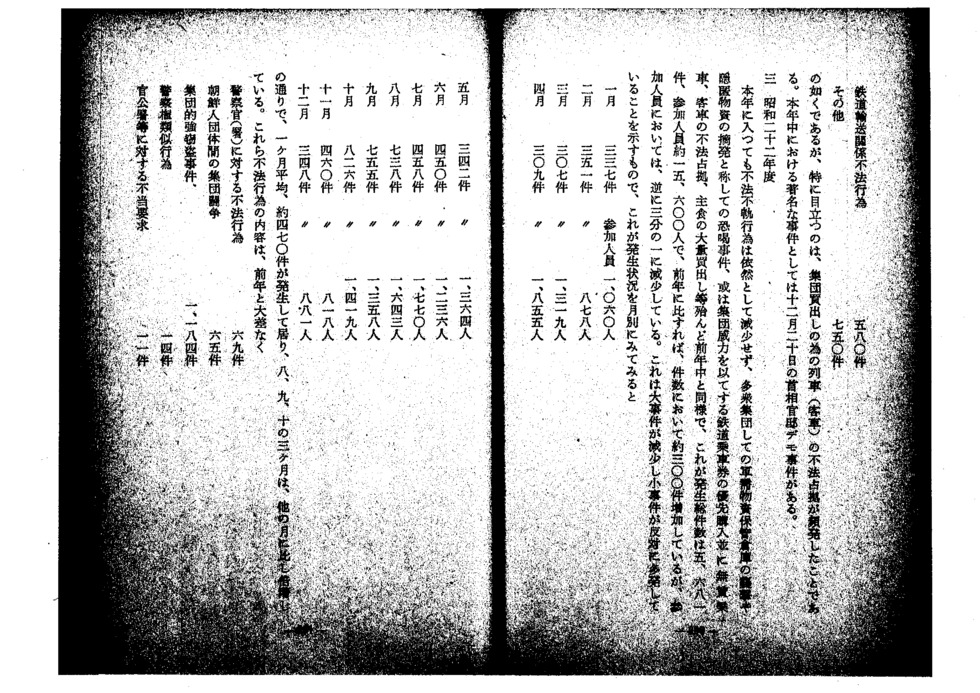

Illegal behavior did not decline in 1947, with attacks by large groups of people on warehouses containing military supplies, extortion on the pretext of uncovering hidden goods, and crowds using pressure to buy train tickets ahead of other passengers, to ride trains without paying, to illegally occupy carriages, and to carry out group kaidashi much the same as the previous year. The total number of cases was 5,681, with around 15,600 people participating. This represented an increase of around 300 in terms of cases, but the number of participants conversely fell to a third as a result of a decline in major incidents, even as numerous small incidents occurred. The breakdown by month was as follows:

January 337 cases 1,060 people involved

February 351 878

March 307 1,319

April 309 1,855

May 342 1,364

June 450 1,236

July 458 1,770

August 738 1,643

September 753 1,358

October 826 1,419

November 460 818

December 348 881

The monthly average was around 470, doubling in the three months of August, September, and October compared to other months. The types of illegal acts that were committed were similar to those in the previous year.

Illegal behavior toward police (stations) 69

Fights between members of Korean associations 65

Gang theft 1,184

Actions imitating police authority 14

Unfair demands on authorities 11

Gang assault and injury 373

Gang fraud and extortion 348

Illegal behavior in relation to rail transport 318

Other 3,299

Compared to the previous year, the most common illegal activities of the previous year—illegal actions occurring in conjunction with unfair demands on authorities, etc. (2,407) and actions imitating police authority (128)—almost vanish, whereas gang theft (572) and gang fraud and extortion (143) double or even triple. Aside from these, fights between members of Korean associations, fights among groups of Japanese and Koreans, and illegal behavior in relation to rail transport, etc., have still not decreased. Notable incidents that year included developments in relation to the February strike and interference with campaign speeches by conservative lawmakers of the Diet.

- Fiscal year 1948

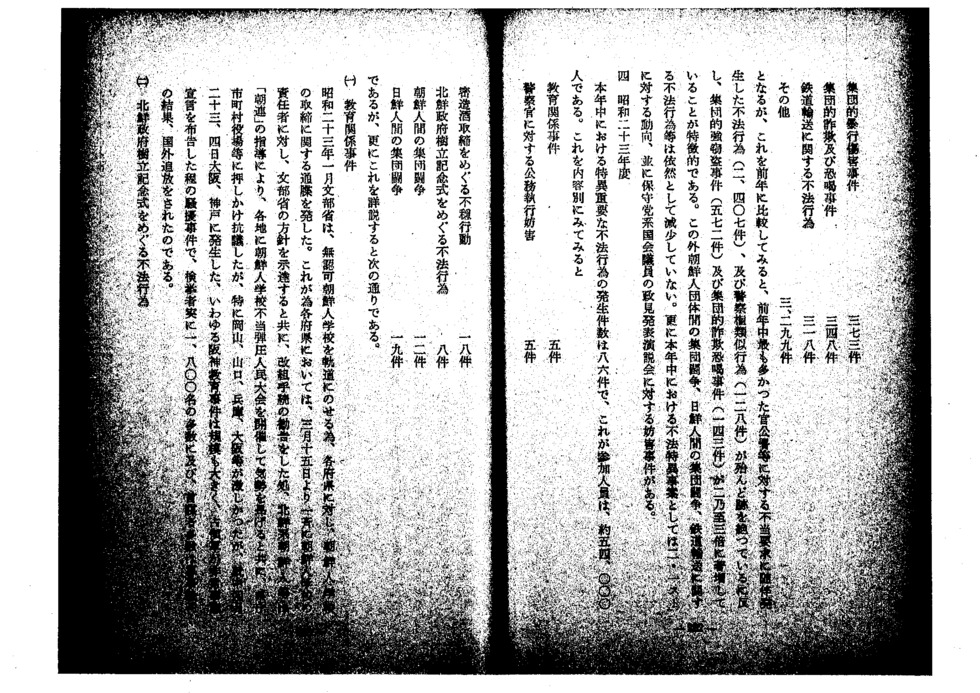

There were 86 key cases of illegal behavior in 1948, with around 54,000 people participating. The types of illegal activities were as follows:

Education-related incidents 5

Interference with the public duties of police officers 5

Threatening behavior in relation to crackdowns on illegally brewed alcohol 18

Illegal behavior related to ceremonies honoring the North Korean government 8

Fights among groups of Koreans 12

Group conflicts between Japanese and Koreans 19

These are explained in more detail below.

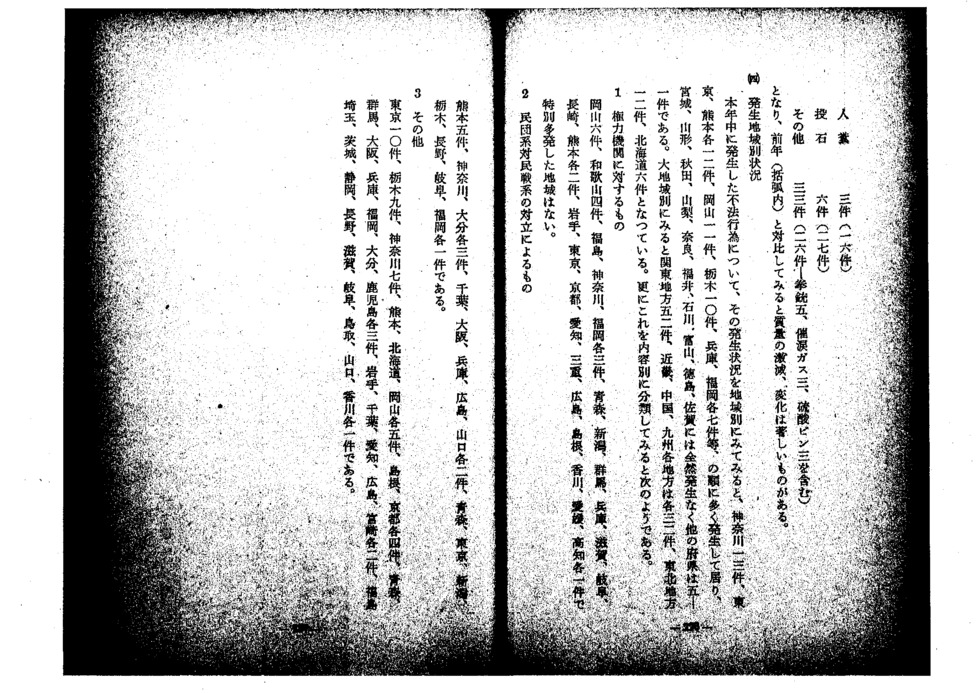

(1) Education-related incidents

In January 1948, the Ministry of Education notified the various prefectures of a crackdown on Korean schools in order to regularize the situation at unlicensed Korean schools. The heads of all Korean schools were notified as of March 15 of the Ministry’s policy and were recommended to undertake reorganization procedures, which prompted North Koreans in particular (led by Choren) to hold rallies protesting the unfair oppression of Korean schools in order to work up public sentiment, while also rushing to protest at municipal offices around the country. Opposition was particularly fierce in Okayama, Yamaguchi, Hyogo, and Osaka. The Hanshin education incident which took place in Osaka and Kobe on April 23 and 24 in particular featured riots on such a scale that the Occupation Forces declared a state of emergency, and 1,800 people were arrested. Many of the ringleaders were tried by military tribunals and deported.

(2) Illegal behavior related to ceremonies honoring the North Korean government

In October 1948, North Korean associations held many ceremonies celebrating the establishment of the North Korean government. The raising of the North Korean flag or the displaying of posters of the flag on these occasions—both of which were prohibited—led to conflict with the MPs and police dealing with these situations in Okayama, Kanagawa, Miyagi, Gifu, Osaka, and Kumamoto, with the 43 suspects all tried before military tribunals.

(3) Conflicts among groups of Koreans

These conflicts among Koreans were rooted in power struggles between Choren and Mindan and between Minsei and Kensei, with three incidents occurring in Hyogo, two each in Osaka and Kanagawa, and one each in Shizuoka, Fukushima, Mie, Yamaguchi, and Gunma. Power struggles based on ideological differences were behind all of the cases, but the immediate motive in an overwhelming number of cases was a desire by Choren to obstruct the formation of Mindan branches.

(4) Fights between groups of Japanese and Koreans

Fights between groups of Japanese and Koreans occurred in Shizuoka and 16 other prefectures, with the Japanese in the majority of cases being peddlers known as yashi, followed by juvenile delinquents and construction workers. While most fights were provoked by trivial arguments, gambling quarrels, and fights over street stall territory, the underlying cause appears to be a collision between the feelings of Koreans as an independent people toward the Japanese, and the feelings of the Japanese about what they perceived as the high-handed behavior of Koreans after the war. These fights were essentially brawls involving numerous people carrying weapons, usually resulting in numerous injuries on both sides. Comparatively large-scale events include the Hamamatsu incident in Shizuoka, the Minamata incident in Kumamoto, and the Goshogawara incident in Aomori.

- Fiscal year 1949

There were 108 incidents of illegal group activity in 1949, with around 20,000 people participating. The breakdown was as follows:

Illegal behavior between groups of Japanese and Koreans 14 cases

Illegal behavior between groups of Koreans 29

Behavior related to crackdowns on making illicit alcohol 31

Illegal behavior toward police (stations) 19

Illegal behavior related to the dissolution of Choren/Minsei 10

Illegal behavior in relation to the closure of Korean schools 5

Compared to the previous year, there were two or even four times as many cases of illegal activity in relation to crackdowns on illicit alcohol production, illegal behavior between groups of Koreans, and illegal behavior toward police officers and police stations, while there were five fewer cases of illegal behavior between groups of Japanese and Koreans. Cases of the latter occurred in the prefectures of Yamaguchi, Tokyo, Ishikawa, Aomori, Nara, Kanagawa, Iwate, Miyagi, Fukushima, Hyogo, Fukui, and Tochigi and involved a total of around 1,000 Koreans and 300 Japanese (mostly peddlers known as yashi). The direct cause in six cases was alcohol consumption, trivial arguments in three cases, a fight over street stall territory in two cases, and other reasons in three cases, but none of the incidents were large in scale. There were 29 cases of illegal behavior between groups of Koreans, involving a total of around 7,000 people. By prefecture, four cases occurred in Yamaguchi, four in Gifu, two each in Chiba, Wakayama, Fukuoka, and Miyagi, and one each in Iwate, Mie, Hiroshima, Hokkaido, Shizuoka, Hyogo, Tokyo, Okayama, Niigata, Oita, Shiga, and Osaka. In seven cases, the direct cause was obstruction of the creation of Mindan branches, in eight cases alcohol consumption or a trivial argument, in four cases a clash between the two sides over commemorating the Fifteenth of August, in two cases the brutalization of a Mindan member, in two other cases attempts to interfere with the pasting of posters, and in four cases another reason. Large-scale incidents that year were the incident involving members of student associations in Tokyo on May 8 and the August 15 Shimonoseki incident.

There were 19 cases of illegal behavior toward police officers and police stations, with two occurring in each of the prefectures of Tokyo, Hiroshima, Fukushima, Kanagawa, and Okayama, and one each in Shimane, Hyogo, Ehime, Aichi, Fukui, Kyoto, Chiba, Shiga, and Iwate. The incidents in question included obstructing police in the conduct of their duties, assaults on police officers, and attacks on police stations and police boxes. Notable incidents that year included interference with public duties in relation to the uncovering of hoarded and concealed goods in Masuda-cho, Shimane Prefecture (39 arrested), an assault on a police officer in a police box in Hongo, Fukui Prefecture (five arrested), obstruction of duties at Chiba Station, Chiba Prefecture (20 arrested), the Japan Steel Works incident in Hiroshima City, the occupation of a police station in Taira City (now part of Iwaki City) Fukushima, and illegal behavior near Okayama Station in relation to the welcoming of Japanese citizens returning from the Soviet Union.

There were three cases of illegal behavior in relation to the dissolution of Choren and Minsei in Yamaguchi, two in Fukuoka, and two each in Ishikawa, Fukui, Kanagawa, and Toyama, with 162 people arrested. Most of the offenses were incidents involving the obstruction of public duties. While there were also many examples of activities carried out by large groups of people to demonstrate their discontent such as violating public safety ordinances and destroying seals on seized property, surprisingly few incidents escalated to the level of illegality. Korean schools all over Japan were closed and seized on October 19, but there was surprisingly little illegal behavior in response to this, with a total of only five cases—four in Kanagawa and one in Chiba—and only 49 arrests for offenses such as the destruction of seals on seized property, obstruction of public duties, unlawful trespass, and destruction of property.

- Fiscal year1950

There were 146 cases of illegal activity in 1950, involving about 4,500 people. The breakdown was as follows:

Illegal behavior toward police officers and police stations 17 cases

Behavior related to crackdowns on making illicit alcohol 2

Fighting between groups of Koreans 21

Fighting between groups of Japanese and Koreans 2

Infringements of Ordinance No. 325 105

All of these types of activities fell compared to the previous year, with illegal activity in relation to crackdowns on illegal alcohol production and fighting between groups of Koreans in particular plunging by around 90 percent. A particular feature of 1950 was the surge in infringements of Ordinance No. 325 (distribution of anti-American and anti-Occupation bills) as a result of the Korean War, accounting for over 70 percent of total cases.

Cases of illegal behavior toward police officers and police stations occurred in Tokyo, Fukuoka, Gunma, Yamanashi, Okayama, Kanagawa, Hyogo, Aichi, Kyoto, and Nagano, and most frequently in Tokyo, Okayama, and Kanagawa, with the best-known case being the Taito Hall incident in Tokyo involving confiscation of former Choren property, the confinement in Kobe of Nagata ward office staff in relation to a dispute over people’s livelihoods, and the obstruction of public duties in the Otsu Employment Bureau and Prosecutor’s Office in Shiga Prefecture. Fights between groups of Koreans occurred in Ibaraki (three cases), Shizuoka (two), Shiga (two), Okayama (two), Akita, Nagano, Tochigi, Osaka, Chiba, Aichi, Mie, Yamaguchi, Tokyo, Fukuoka, Hyogo, and Oita (one in each of these prefectures). Most of these fights were power struggles between the former Choren and Mindan, and the immediate causes were arguments (in six cases), attempts to obstruct the creation of Mindan branches (in five cases), consumption of alcohol (in four cases), and other factors. A comparatively large-scale incident involved an attempt to obstruct the formation of a Mindan branch in Yokoshiba-cho, Chiba Prefecture.

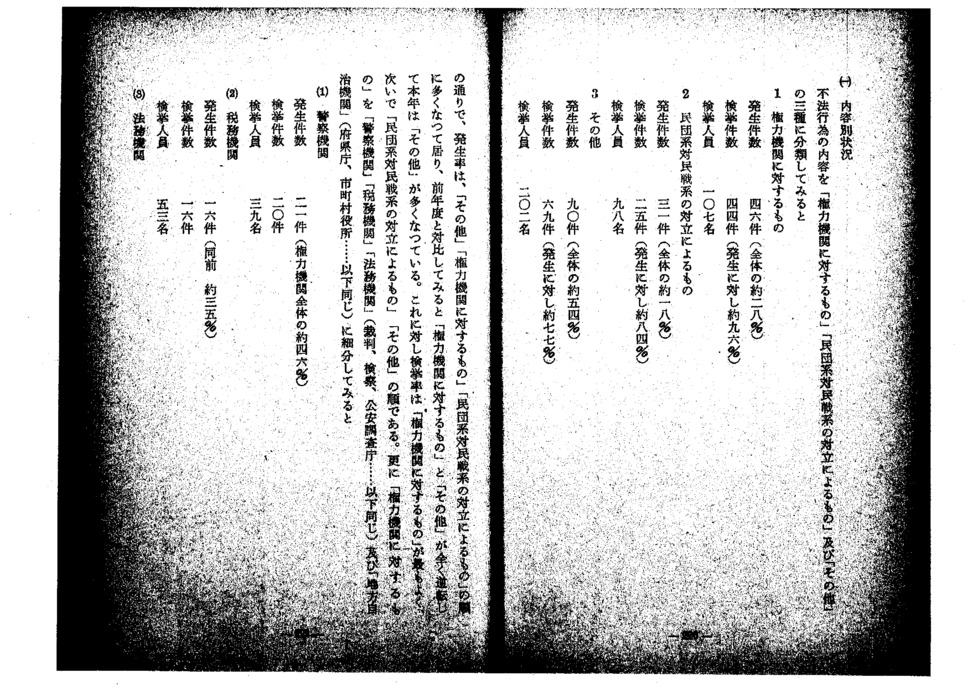

- Fiscal year1951

There were 211 cases of illegal activity in 1951, involving about 7,200 people. The breakdown was as follows:

Illegal behavior toward police officers and police stations 16 cases

Activities related to crackdowns on making illegal alcohol 25

Fighting between groups of Koreans 14

Fighting between groups of Japanese and Koreans 3

Infringements of Ordinance No. 325 153

Total cases were therefore up around 50 percent. The main rates of increase were related to Ordinance No. 325 infringements (around 31 percent) and illegal activity in relation to crackdowns on illegal alcohol production (around 92 percent). There was no change in cases relating to illegal behavior toward police officers and police stations or to fighting between groups of Japanese and Koreans, while fighting between groups of Koreans fell by around 50 percent, completely the opposite of what might have objectively been expected given the situation at the time. The main cases of illegal behavior toward police officers and police stations included an acid bomb attack in relation to the confiscation of former Choren property in Yokkaichi City, Mie Prefecture, a tear gas attack targeting the Higashinari Police Station in Osaka City, resistance to an investigation into an Ordinance No. 325 infringement at the Tokyo Oji Korean Junior High School, and a demonstration against forced repatriation in Hino-cho, Shiga Prefecture that was carried out by protestors riding on bicycles. While fighting between groups of Koreans declined in terms of the number of cases, there were some major incidents, including a large-scale brawl in Yamato-cho, Kanagawa and an attack on a Mindan-managed factory producing military supplies in Osaka City.

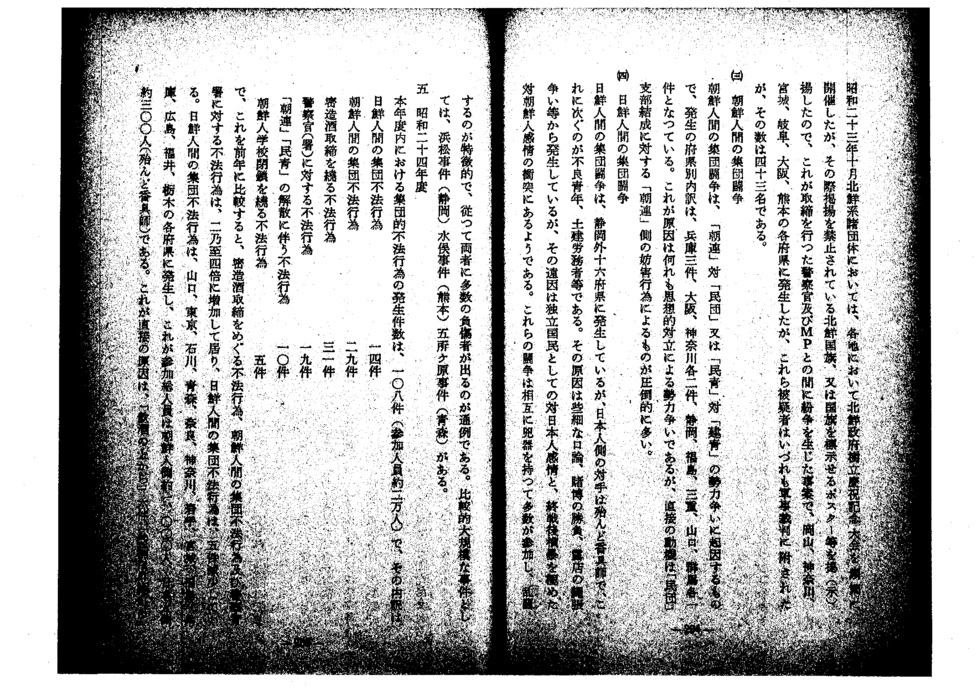

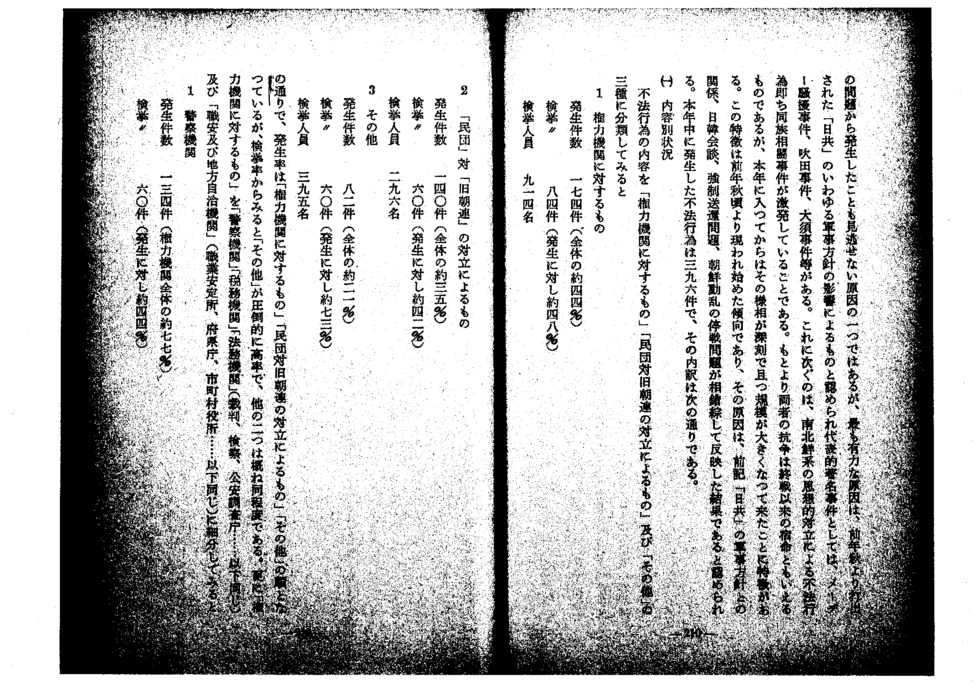

- Fiscal year1952

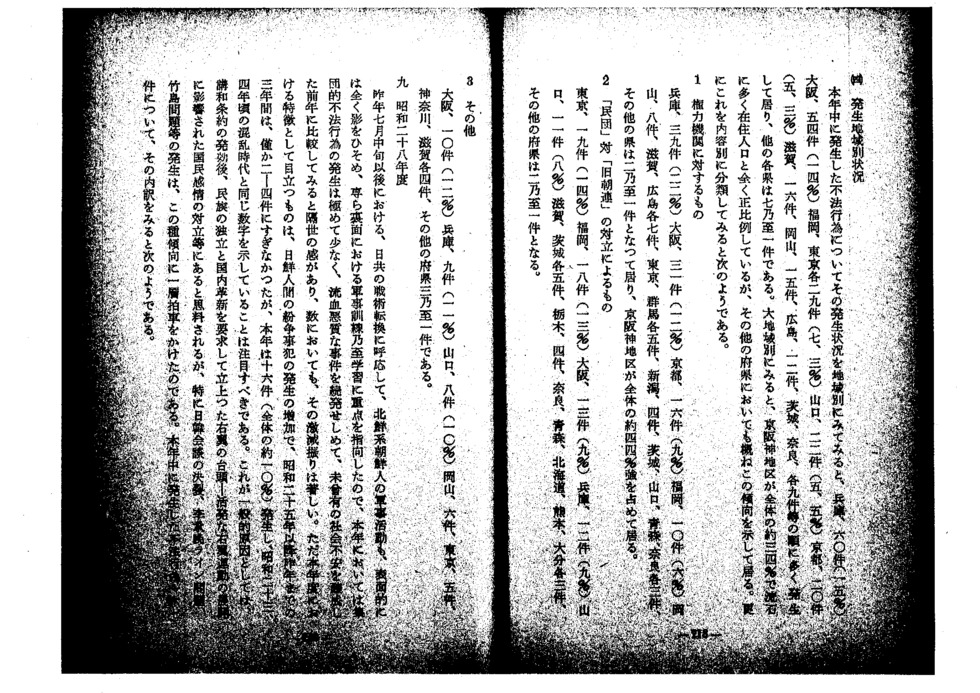

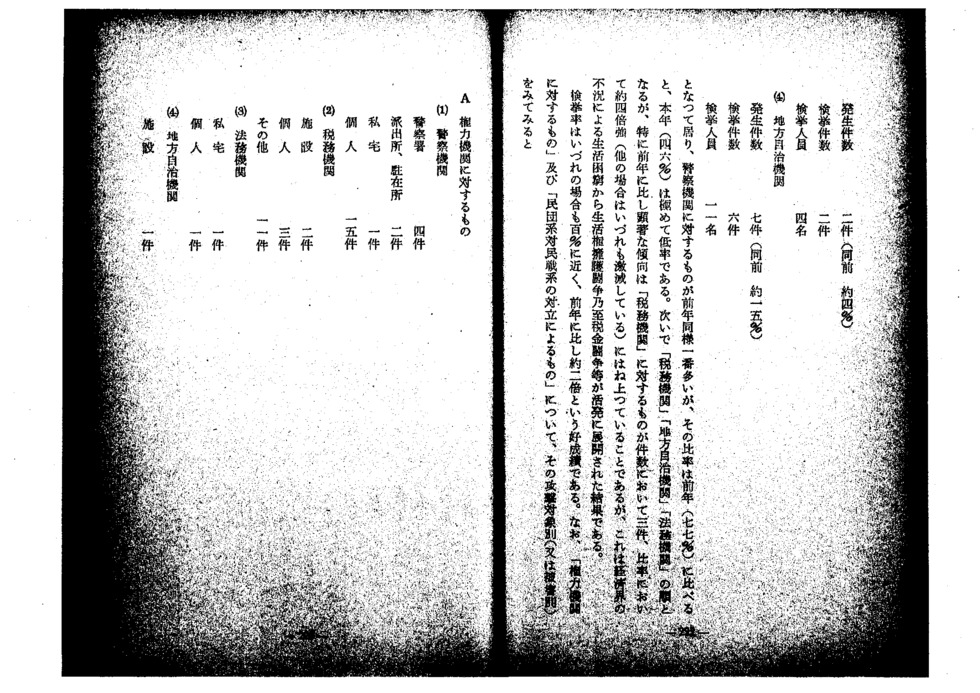

Illegal activity in 1952 was characterized by the many cases that targeted various institutions of power. This insurgency, moreover, was organized and rehearsed, while many of the weapons that were employed used chemicals (albeit in a crude fashion). While the Koreans themselves were certainly a factor in this trend, it is recognized that the more important factor was the influence of the policy of military action adopted by the JCP the previous autumn, with major incidents including the May Day riots, the Suita incident, and the Osu incident. Next was a rash of illegal activity driven by ideological differences between North and South Koreans—in other words, intra-ethnic fighting. While the struggle between them could be said to be their fate since the end of the war, it became much more serious and large-scale as of 1952. This trend became marked around autumn the previous year, caused by the interaction of factors such as the above-mentioned JCP military policy, the Japan-South Korea summit talks, the forced repatriation program, and the Korean War armistice issue. There were 396 incidents of illegal activity in 1952, the breakdown of which is as follows:

(1) Breakdown of activities

Breaking down the illegal activities into “activities targeting institutions of power,” “activities arising from conflict between Mindan and the former Choren,” and “other” produces the following results:

(a) Activities targeting institutions of power

No. of cases: 174 (equal to about 44 percent of all cases of illegal activities)

No. of arrests: 84 (about 48 percent of the cases involving institutions of power)

No. of people arrested: 914

(b) Activities arising from conflict between Mindan and the former Choren

No. of cases: 140 (equal to about 35 percent of all cases of illegal activities)

No. of arrests: 60 (about 42 percent of the cases involving Mindan/Choren disputes)

No. of people arrested: 296

(c) Other

No. of cases: 82 (equal to about 21 percent of all cases of illegal activities)

No. of arrests: 60 (about 73 percent of the cases involving "other" factors)

No. of people arrested: 395

From highest to lowest, the rate of incidence was “activities targeting institutions of power,” “activities arising from conflict between Mindan and the former Choren,” and “other,” but the “other” category had by far the highest rate of arrests, with the other two at approximately the same level. Dividing “activities targeting institutions of power” by their target into “police institutions,” “tax institutions,” “judicial institutions” (courts, prosecutors, Public Security Intelligence Agency; same below), and “employment bureaus and local government institutions” (employment bureaus, prefectural offices, municipal offices; same below), the following results emerge:

1 Police institutions

No. of cases: 134 (equal to about 77 percent of the incidents against institutions of power)

No. of arrests: 60 (about 44 percent of the cases involving police institutions)

No. of people arrested: 789

2 Tax institutions

No. of cases: 13 (equal to about 7.5 percent of the incidents against institutions of power)

No. of arrests: 6 (about 46 percent of the cases involving tax institutions)

No. of people arrested: 38

3 Judicial institutions

No. of cases: 11 (equal to about 6.3 percent of the incidents against institutions of power)

No. of arrests: 8 (about 72 percent of the cases involving judicial institutions)

No. of people arrested: 46

4 Employment bureaus and local government institutions

No. of cases: 16 (equal to about 9.2 percent of the incidents against institutions of power)

No. of arrests: 10 (about 63 percent of the cases involving employment/local govt. institutions)

No. of people arrested: 41

Cases targeting police institutions were by far the most numerous, with all the others occurring at approximately the same frequency. This high rate may have arisen from a whole range of motivations, such as dislike of the police as the institution of power with which people most frequently came into contact, or the desire to gain greater influence of various types by harming the police, who were regarded as representative of all institutions of power. However, at the same time, it should be noted that the highest rate of challenges was being made upon the most heavily armed and effective of the various institutions of power. The large number of incidents involving police institutions could be regarded as a reflection of the faithful implementation of the JCP’s policy of militancy. The highest rate of arrests was for incidents involving “judicial institutions,” followed by incidents involving “employment bureaus and local government institutions” and “tax institutions,” with incidents involving “police institutions,” ironically, generating the lowest rate of arrests.

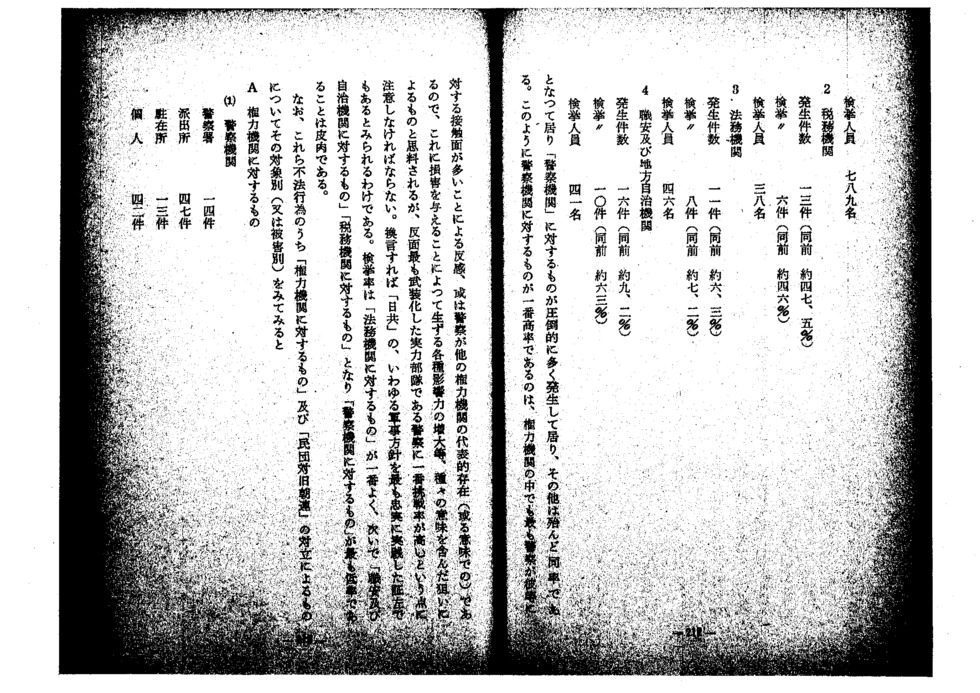

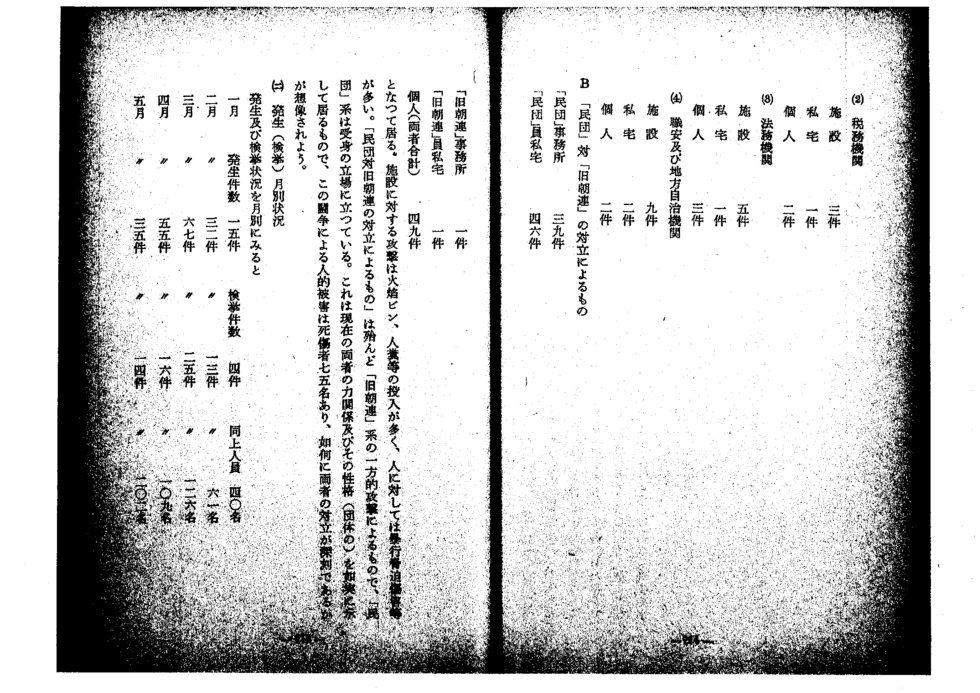

Looking at the targets (or victims) of illegal activities aimed at institutions of power and those related to the Choren-Mindan conflict, the following breakdown emerges:

- Illegal activities targeting institutions of power

(1) Police institutions

Police stations 14 cases

Local police stations 47

Police boxes 13

Individuals 42

(2) Tax institutions

Facilities 3

Private homes 1

Individuals 2

(3) Judicial institutions

Facilities 5

Private homes 1

Individuals 3

(4) Employment bureaus and local government institutions

Facilities 9

Private homes 2

Individuals 2

- Illegal activities related to the Choren-Mindan conflict

Mindan offices 39

Private homes of Mindan members 46

Choren offices 1

Private homes of Choren members 1

Individuals (total from both sides) 49

In the case of attacks on facilities, most were made with gasoline bombs or thrown human excrement, while most attacks on people were in the form of assaults, threats, and infliction of injury. Most illegal activities related to the Choren-Mindan conflict were attacks by former Choren members, with Mindan members on the receiving end of the attacks. This accurately reflects the power relationship between the two groups as well as their respective natures, with the 75 casualties resulting from the conflict demonstrating the seriousness of the standoff.

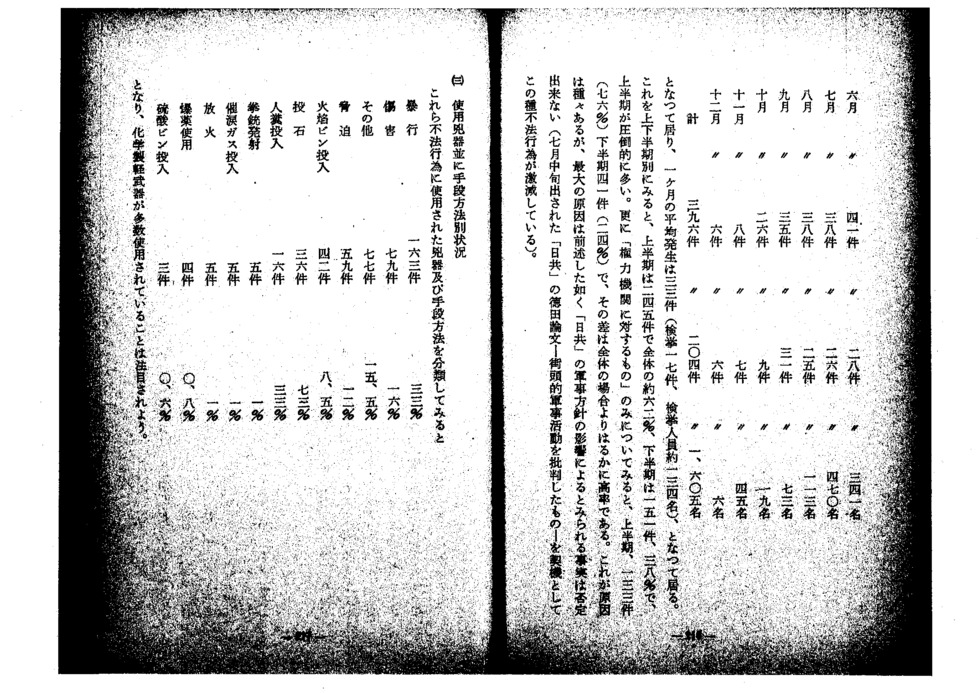

(2) Cases (arrests) by month

The figures for cases and arrests by month were as follows:

January No. of cases 15 No. of arrests 4 No. of people arrested 40

February 32 13 61

March 67 25 126

April 35 16 109

May 35 14 202

June 41 28 341

July 38 26 470

August 38 25 113

September 35 31 73

October 26 9 19

November 8 7 45

December 6 6 6

Total 396 204 1,605

There were an average of 33 cases, 17and around 134 people arrested per month. In terms of the first and second half of the year, there were 245 cases in the first half, or around 62 percent, and 151, or 38 percent, in the second half, with by far the most cases occurring in the first half. Looking only at those cases targeting institutions of power, 133 (76 percent) occurred in the first half of the year and 41 (24 percent) in the second half of the year, a much greater disparity compared to all other categories. While various factors were behind that result, the biggest was undeniably the influence of the above-mentioned JCP military policy (this type of illegal behavior drops abruptly with the appearance in mid-July of an essay by the JCP’s Kyuichi Tokuda that criticizes street violence).

(3) Breakdown by weapons/means used